Contributor Bio

Andrew Koenig and Caroline Tew and Cecilia Weddell and Chloe Garcia Roberts and Christian Schlegel and Christina Thompson and Laura Healy and M. Rachel Thomas and Major Jackson and Miciah Bay Gault and Rachel Ahearn

More Online by Andrew Koenig, Caroline Tew, Cecilia Weddell, Chloe Garcia Roberts, Christian Schlegel, Christina Thompson, Laura Healy, M. Rachel Thomas, Major Jackson, Miciah Bay Gault, Rachel Ahearn

What We’re Reading

by the Staff at Harvard Review

As we approach the end of this crazy year, the staff of Harvard Review would like to share the books that got us through the past twelve months. From bestsellers to indie treasures, in e-books and audiobooks and good, old-fashioned print, in verse and prose, from short story to history, here’s a sampler of what we’ve been reading.

Christina Thompson, Editor

I’ve had The Lost Books of the Odyssey by Zachary Mason (FSG, 2010) on my To Read list for years—possibly since it first came out in 2007 from a tiny independent press in Buffalo, NY, called Starcherone Books, but definitely since it was republished to acclaim in an edited version by FSG.  Not everyone will be able to get their hands on the original edition, but it’s an interesting comparison. The original features a longish introduction, setting the book up as a found manuscript with a complicated backstory and introducing its putative decoder in the character of a professor of modern languages with “some small fame in cryptographic circles.” While all of this is amusing, the decision by FSG to strip away the conceptual envelope and present the “Lost Books”—brilliant short riffs on the characters and events of the Odyssey and Iliad—without commentary was a good one. It allows us to see immediately what is so brilliant about this book: the deep familiarity with the source material, the strangely fresh and yet classical-feeling prose, the boundless imagination of the author. These inventive additions to the Homeric canon feel as timeless as the Odyssey itself, and a book I was pretty sure I was going to like turns out to be a book I absolutely love.

Not everyone will be able to get their hands on the original edition, but it’s an interesting comparison. The original features a longish introduction, setting the book up as a found manuscript with a complicated backstory and introducing its putative decoder in the character of a professor of modern languages with “some small fame in cryptographic circles.” While all of this is amusing, the decision by FSG to strip away the conceptual envelope and present the “Lost Books”—brilliant short riffs on the characters and events of the Odyssey and Iliad—without commentary was a good one. It allows us to see immediately what is so brilliant about this book: the deep familiarity with the source material, the strangely fresh and yet classical-feeling prose, the boundless imagination of the author. These inventive additions to the Homeric canon feel as timeless as the Odyssey itself, and a book I was pretty sure I was going to like turns out to be a book I absolutely love.

Keeping with the Homeric theme, I also set my sights on Circe by Madeline Miller (Little Brown, 2018). I wasn’t sure what I was going to make of this enormous bestseller, which I ended up listening to as an audiobook. The narrator, Perdita Weeks, does an excellent job of capturing the many moods of the characters, both mortal and divine, and despite my prejudices (would it be a sort of grey-eyed Athena in Monterey?), I was entirely won over by Miller’s rich mythic world, with its selfish immortals and hapless humans, and her spirited, event-filled (i.e., Homeric) storytelling.

Major Jackson, Poetry Editor

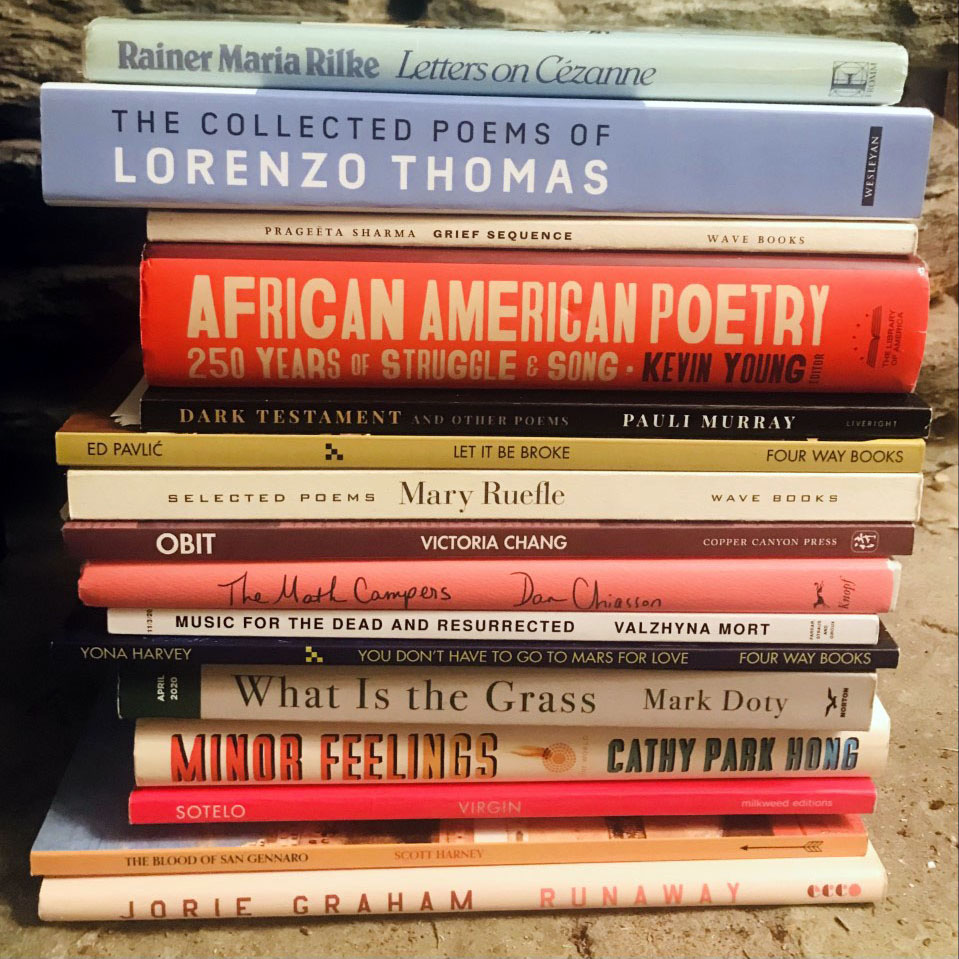

More than ever, I found myself reaching for books that could further my understanding of the environmental and political challenges as well as the global contagion that defined much of the year. I wanted the artfulness and sway of lyric structures—Dan Chiasson’s The Math Campers (Knopf, 2020); Jorie Graham’s Runaway (Ecco, 2020); Prageeta Sharma’s Grief Sequence (Wave, 2019)—as well as critical and insightful intelligence that could interrupt my assumptions about race and art—The Collected Poems of Lorenzo Thomas (Wesleyan University Press, 2019), Cathy Park Hong’s Minor Feelings (One World, 2020), Ed Pavlić’s Let It Be Broke (Four Way Books, 2020). I wanted the simplicity and passion of song and witness—Analicia Sotelo’s Virgin (Milkweed Editions, 2018); Pauli Murray’s Dark Testament (Liveright, 2018).

I read many anthologies this year in response to the pandemic, but African American Poetry: 250 Years of Struggle & Song, edited by Kevin Young (Library of America, 2020), arrived this fall like a big punctuation mark. I also desired not so much an escape from the headlines as the sort of transitory departure that poetry permits. Even in the most mundane activities, brushing my teeth or walking Buzz, my elder golden, I knew something terrible was happening somewhere in the world, and this produced at times a frayed consciousness, pockets of grief and recognition that our daily rituals often eclipse. These books held aloft the possibilities of tomorrow, hinting at how we suffer, and yet, as Pauli Murray declares in her poem “Prophecy,” how we “live on in the rivers of history.”

I read many anthologies this year in response to the pandemic, but African American Poetry: 250 Years of Struggle & Song, edited by Kevin Young (Library of America, 2020), arrived this fall like a big punctuation mark. I also desired not so much an escape from the headlines as the sort of transitory departure that poetry permits. Even in the most mundane activities, brushing my teeth or walking Buzz, my elder golden, I knew something terrible was happening somewhere in the world, and this produced at times a frayed consciousness, pockets of grief and recognition that our daily rituals often eclipse. These books held aloft the possibilities of tomorrow, hinting at how we suffer, and yet, as Pauli Murray declares in her poem “Prophecy,” how we “live on in the rivers of history.”

Miciah Bay Gault, Guest Fiction Editor

The Shame by Makenna Goodman (Milkweed Editions, 2020) is one of the best debuts I’ve read in a long time. This remarkable novel recounts the middle-of-the-night journey of a young Vermont wife and mother from her rural home to New York City, as well as her dark spiral into obsession via social media with an urban ceramicist she’s never met. The bold first-person narration is a torrent of humor, self-doubt, stifled ambition, and saucy asides. Another strange and gorgeous novel, The Illness Lesson by Clare Beams (Doubleday, 2020) takes place in nineteenth-century New England at a remote girls’ school, where teachers and students are unsettled by the arrival of flocks of mysterious bright red birds. The Illness Lesson is many things: a historical novel that alludes to Little Women’s Louisa May Alcott and her transcendentalist father; a speculative wonder that paints both landscape and unraveling constitutions in delicate, startling prose; and a scathing commentary on the ways in which women’s desires and bodies are governed.

Although I’ve read The Manual of Detection by Jedediah Berry (Penguin, 2009) before, when I recently assigned the first chapter to my students I couldn’t stop re-reading. A kind of speculative detective novel, this book is a delight on the every level—hilarious, beautiful, strange, and brimming with foggy, old-fashioned, circus-y, oneiric charm. I’ve come to this realization a bit late in life, but it turns out I love mysteries, and I’m grateful to Sarah Stewart Taylor’s The Mountains Wild (Minotaur, 2020) for opening up a rich new landscape of reading for me. The book’s detective, a single mom from Long Island, is brave, loyal, intelligent, dogged—and I missed her when I was finished with the book.

Although I’ve read The Manual of Detection by Jedediah Berry (Penguin, 2009) before, when I recently assigned the first chapter to my students I couldn’t stop re-reading. A kind of speculative detective novel, this book is a delight on the every level—hilarious, beautiful, strange, and brimming with foggy, old-fashioned, circus-y, oneiric charm. I’ve come to this realization a bit late in life, but it turns out I love mysteries, and I’m grateful to Sarah Stewart Taylor’s The Mountains Wild (Minotaur, 2020) for opening up a rich new landscape of reading for me. The book’s detective, a single mom from Long Island, is brave, loyal, intelligent, dogged—and I missed her when I was finished with the book.

Normal People by Sally Rooney (Hogarth, 2019): loved it, loved it. It defies all logic. When I try to summarize it, the plot feels slight, the characters prosaic, and the themes ordinary, yet this book is unexpectedly riveting. What kind of magical genius is Sally Rooney to pull that off? Other favorites this year included Jesmyn Ward’s National Book Award-winning Salvage the Bones (Bloomsbury USA, 2011), which I read on a weekend camping trip, staying up until it was too dark to see, trying to read just a few more lines by firelight; Friday Black by Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah (Mariner Books, 2018), which I loved for the way the stories work as a collection; and Madness, Rack, and Honey, a collection of lectures by Mary Ruefle (Wave Books, 2012). This book is, among other things, a love letter to Emily Dickinson and an exploration of why we write. “I used to think I wrote because there was something I wanted to say,” writes Ruefle. “And then I thought, ‘I will continue to write because I have not yet said what I wanted to say’; but I know now I continue to write because I have not yet heard what I have been listening to.”

Chloe Garcia Roberts, Managing Editor

This is my once and future book stack. My favorite books this annus horribilis include When Montezuma Met Cortés by Matthew Restall (Ecco, 2018), a mind-bending account of a story I thought I knew, though Restall showed me otherwise. Montezuma just barely beat out Mr. Fortune by Sylvia Townsend Warner (NYRB Classics, 2011), who is quickly becoming one of my favorite authors, and Charles Dickens’s Barnaby Rudge, which was a welcome refuge from the storm.

I’m also currently reading the books of a few recent HR contributors: Benjamin Gucciardi’s surreal and devastating I Ask My Sister’s Ghost (New Michigan Press, 2020) and Patricia Vigderman’s The Real Life of the Parthenon (Mad Creek Books, 2018), Greece being my desired flavor of travel porn in this moment of stasis. On and off I’m working through Denise Riley’s Time Lived, Without Its Flow (Picador, 2019), which is such a clear-eyed dissection of grief that I have to read it in small doses; For Isabel by Antonio Tabucchi (Archipelago, 2017), whose discrete and accreting chapters make it nice morning-coffee reading; and Julio Glockner’s Los Volcanes Sagrados (Debolsillo, 2019), which is a window into volcano worship and shape-shifting volcano deities in Mexico.

I’m also currently reading the books of a few recent HR contributors: Benjamin Gucciardi’s surreal and devastating I Ask My Sister’s Ghost (New Michigan Press, 2020) and Patricia Vigderman’s The Real Life of the Parthenon (Mad Creek Books, 2018), Greece being my desired flavor of travel porn in this moment of stasis. On and off I’m working through Denise Riley’s Time Lived, Without Its Flow (Picador, 2019), which is such a clear-eyed dissection of grief that I have to read it in small doses; For Isabel by Antonio Tabucchi (Archipelago, 2017), whose discrete and accreting chapters make it nice morning-coffee reading; and Julio Glockner’s Los Volcanes Sagrados (Debolsillo, 2019), which is a window into volcano worship and shape-shifting volcano deities in Mexico.

Future reading for a home-bound vacation, kindly sent to me by friends at NYRB, include Celia Paul’s Self Portrait, Ge Fei’s Peach Blossom Paradise, and Guido Morselli’s Dissipatio H.G (all NYRB, 2020). Onward to 2021!

Cecilia Weddell, Associate Editor

Many of 2020’s reads took me armchair traveling, through both time and space. I’ve found myself unexpectedly away from my personal bookshelves this year, so I’m grateful to World Literature Today, an international literary journal out of the University of Oklahoma, for bringing literary surprises from all over directly to the mailbox. This fall semester was the second time I taught Yanick Lahens’s Moonbath, translated by Emily Gogolak (Deep Vellum, 2017), and on every reread of this multigenerational Haitian novel I find more complexity and beauty in its pages. Carmen Boullosa’s Texas: The Great Theft, translated by Samantha Schnee (Deep Vellum, 2014) took me back to the mid-1800s on the southernmost border between the US and Mexico; Notes of a Crocodile by Qiu Miaojin, translated by Bonnie Huie (NYRB Classics, 2017) took me to college classrooms and shared apartments in 1980s Taipei; and, during bedtime reading sessions with my seven-year-old nephew, Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (Macmillan, 1865; we read it in a remaindered 2015 edition) took us down the rabbit hole into a world of … well, wonders.

Many of 2020’s reads took me armchair traveling, through both time and space. I’ve found myself unexpectedly away from my personal bookshelves this year, so I’m grateful to World Literature Today, an international literary journal out of the University of Oklahoma, for bringing literary surprises from all over directly to the mailbox. This fall semester was the second time I taught Yanick Lahens’s Moonbath, translated by Emily Gogolak (Deep Vellum, 2017), and on every reread of this multigenerational Haitian novel I find more complexity and beauty in its pages. Carmen Boullosa’s Texas: The Great Theft, translated by Samantha Schnee (Deep Vellum, 2014) took me back to the mid-1800s on the southernmost border between the US and Mexico; Notes of a Crocodile by Qiu Miaojin, translated by Bonnie Huie (NYRB Classics, 2017) took me to college classrooms and shared apartments in 1980s Taipei; and, during bedtime reading sessions with my seven-year-old nephew, Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (Macmillan, 1865; we read it in a remaindered 2015 edition) took us down the rabbit hole into a world of … well, wonders.

Andrew Koenig, Book Review Editor

Lorrie Moore is one of those authors whose work I’ve put off reading, saying “I’ll get around to it someday.” This year, with the release of her Collected Stories (Everyman’s Library, 2020), I finally got around to it. I was initially skeptical of the collection, which simply presents the stories A–Z with no other organizing principle. It didn’t need one; every single story is worth reading. Whether from her early, middle, or late phases—“The Kid’s Guide to Divorce” (1981), “You’re Ugly, Too” (1989), “People Like That Are The Only People Here” (1996)—Moore’s stories are alert to the ways we deceive and are undeceived, probing (but not unsparing) in their treatment of the human heart. I missed Philip Boehm’s justly celebrated translation of Malina by Ingeborg Bachmann (New Directions, 2019) when it came out. Bachmann’s only novel, it details the narrator’s relationship with two men in an apartment building in mid-century Vienna. With its elliptical dialogue, cerebral analyses of love, and magnificent fairytale-like interludes, it reads like nothing else I’ve encountered in the past year.

A. S. Byatt’s Possession (Vintage, 1990) turns thirty this year. Byatt is one of our most eloquent writers on the perils and pleasures of reading and rereading, and in this 500-page literary mystery about two fictitious Victorian poets, she pulls off a rare feat: inventing two historical personages who are totally convincing. (Byatt’s poems had me fooled for the first 100 pages.) If you didn’t go for Martin Amis’s 2020 autobiographical novel, Inside Story, I suggest returning to one of his earlier works: the salacious, beer-sodden London Fields (Everyman Classics, 2014; 1989). A toff, a bombshell, and a drunken dart-thrower are the three principals in this cat-and-mouse detective story, which is Amis at his best: risqué, brilliant, and laugh-out-loud funny. And for the anti-Amis reader, Tragedy (Yale University Press, 2020) by literary critic and Amis rival Terry Eagleton. Tragedy, one in a series of recent short books by Eagleton on big subjects (Hope, Humour, etc.), offers a lucid introduction to Greek tragedy by England’s preeminent literary critic. Eminently readable and helpful, it is a perfect primer for students and non-students alike.

A. S. Byatt’s Possession (Vintage, 1990) turns thirty this year. Byatt is one of our most eloquent writers on the perils and pleasures of reading and rereading, and in this 500-page literary mystery about two fictitious Victorian poets, she pulls off a rare feat: inventing two historical personages who are totally convincing. (Byatt’s poems had me fooled for the first 100 pages.) If you didn’t go for Martin Amis’s 2020 autobiographical novel, Inside Story, I suggest returning to one of his earlier works: the salacious, beer-sodden London Fields (Everyman Classics, 2014; 1989). A toff, a bombshell, and a drunken dart-thrower are the three principals in this cat-and-mouse detective story, which is Amis at his best: risqué, brilliant, and laugh-out-loud funny. And for the anti-Amis reader, Tragedy (Yale University Press, 2020) by literary critic and Amis rival Terry Eagleton. Tragedy, one in a series of recent short books by Eagleton on big subjects (Hope, Humour, etc.), offers a lucid introduction to Greek tragedy by England’s preeminent literary critic. Eminently readable and helpful, it is a perfect primer for students and non-students alike.

Christian Schlegel, Book Review Editor

In 2020 I admired

Ruth Wilson Gilmore’s Golden Gulag (University of California Press, 2007)

Ruth Wilson Gilmore’s Golden Gulag (University of California Press, 2007)

David Antin’s talking at the boundaries (New Directions, 1976)

Anna Wiener’s Uncanny Valley (MCD/FSG, 2020)

Elizabeth Hardwick’s Sleepless Nights (NYRB Classics, 2001)

Alf Evers’s The Catskills (Doubleday, 1972).

I’m partway through and moved by

H. G. Haile’s translation of The History of Doctor Johann Faustus (University of Illinois Press, 1965)

Fred Moten’s “Seeing Things” (on my friend Ben’s recommendation, from Moten’s Stolen Life, Duke University Press, 2018)

David Treuer’s The Heartbeat of Wounded Knee (Riverhead, 2019),

and I can’t wait to read

Mieko Kawakami’s Breasts and Eggs, translated by Sam Bett and David Boyd (Europa Editions, 2020).

Laura Healy, Digital Editor

The pandemic pushed me to read more books off my own shelves, and realizing that women were underrepresented there, I decided to devote 2020 to reading only books by women. I had started the year reading Jill Lepore’s These Truths: A History of the United States (W. W. Norton, 2018), which gave me a useful lens through which to view this year’s events. After that, I pulled out some books I already had by the usual suspects (Zadie Smith, Annie Dillard, Hilary Mantel, Joan Didion) and set about acquiring a few classics I had missed (Jean Rhys, Zora Neale Hurston) and some newer titles. I particularly enjoyed An American Marriage by Tayari Jones (Algonquin, 2018) and Educated by Tara Westover (Random House, 2018), which explore two different corners of the American experience. I did allow one exception to my rule, Daily Rituals: Women at Work by Mason Currey (Knopf, 2019), because it gave me some good insights into the working habits of women artists and introduced me to some characters I had never heard of. I didn’t make it through every book in my stack, but overall it was a fruitful exercise because it forced me to put a bit more thought into my reading list and fill in a few gaps.

The pandemic pushed me to read more books off my own shelves, and realizing that women were underrepresented there, I decided to devote 2020 to reading only books by women. I had started the year reading Jill Lepore’s These Truths: A History of the United States (W. W. Norton, 2018), which gave me a useful lens through which to view this year’s events. After that, I pulled out some books I already had by the usual suspects (Zadie Smith, Annie Dillard, Hilary Mantel, Joan Didion) and set about acquiring a few classics I had missed (Jean Rhys, Zora Neale Hurston) and some newer titles. I particularly enjoyed An American Marriage by Tayari Jones (Algonquin, 2018) and Educated by Tara Westover (Random House, 2018), which explore two different corners of the American experience. I did allow one exception to my rule, Daily Rituals: Women at Work by Mason Currey (Knopf, 2019), because it gave me some good insights into the working habits of women artists and introduced me to some characters I had never heard of. I didn’t make it through every book in my stack, but overall it was a fruitful exercise because it forced me to put a bit more thought into my reading list and fill in a few gaps.

M. Rachel Thomas, Senior Reader

The most important book I read this year was The New Jim Crow by Michelle Alexander (The New Press, new edition, 2020), about the American crisis of mass incarceration, the prison-industrial complex that supports it, the politics and policies that created it, and the way the system aggressively disadvantages Black and brown communities. Some of the statistics in this book are not just shocking, but deeply shameful. History of Love by Nicole Krauss (W. W. Norton, 2005) is a lovely little novel, surprising in form, style, and substance. Imagine a lonely old man who is, by his own description, ridiculous, irrelevant, and unloved. Then take this old man and make him the hero of a tragic love story—rapturously tender and somehow entirely un-saccharine—that spans decades. Then write it like a mystery, put a novel within the novel, and populate it with a bunch of other characters who are generationally and geographically diverse, and you have the beginning of an idea of what Krauss has done.

The most important book I read this year was The New Jim Crow by Michelle Alexander (The New Press, new edition, 2020), about the American crisis of mass incarceration, the prison-industrial complex that supports it, the politics and policies that created it, and the way the system aggressively disadvantages Black and brown communities. Some of the statistics in this book are not just shocking, but deeply shameful. History of Love by Nicole Krauss (W. W. Norton, 2005) is a lovely little novel, surprising in form, style, and substance. Imagine a lonely old man who is, by his own description, ridiculous, irrelevant, and unloved. Then take this old man and make him the hero of a tragic love story—rapturously tender and somehow entirely un-saccharine—that spans decades. Then write it like a mystery, put a novel within the novel, and populate it with a bunch of other characters who are generationally and geographically diverse, and you have the beginning of an idea of what Krauss has done.

In Twilight of Democracy (Doubleday, 2020), Anne Applebaum, a Pulitzer Prize–winning historian, explores the emotional and psychological appeal of demagoguery and nationalism and reframes the current political struggles not as left versus right but as authoritarian versus democratic, emotional versus rational. Don’t be scared off by the doomsday title; Applebaum’s style is extremely engaging, and she illustrates her points by weaving in and out of friendships and professional relationships across decades. At 224 pages (or four hours on audiobook) it’s also a quick read. I love books that transport me to places I’ve never been, and White Teeth by Zadie Smith (Hamish Hamilton, 2000) does a lot of this as it follows a huge cast of characters from nineteenth-century Jamaica to 1970s London to 1940s Germany and back again. The book touches on a lot of themes—racism, colonialism, feminism, fundamentalism—and doesn’t quite manage to wrap up each thread. But Smith’s writing is dazzling and fun.

I’ve never read a Stephen King novel and it’s unlikely I will. But this “memoir of the craft,” as King calls On Writing (Scribner, 2000), is a book I come back to time and again for excellent writing advice and renewed inspiration. In a recent episode of the podcast Bill Gates and Rashida Jones Ask Big Questions, Gates praised the Israeli historian Yuval Noah Harari’s “broad way of looking at things [which is] really brilliant.” An example might be Harari’s way of describing corporations as “stories invented by powerful shamans called lawyers,” or his argument that wheat may have domesticated humans, not the other way around. In Sapiens (Harper, 2014), Harari applies this thinking to the history of Homo sapiens in something like a report card for humanity. Spoiler alert: we’re not getting very good grades.

Caroline Tew, Intern

When lockdown hit, two friends and I created a virtual book club with the ambitious goal of reading a book a week. Not only did our weekly Zooms keep me sane, they also introduced me to some of my favorite books of the year: The Vanishing Half by Brit Bennett (Riverhead, 2020), Girl, Woman, Other by Bernardine Evaristo (Grove Press, 2019), Middlemarch by George Eliot, and Cloud Atlas by David Mitchell (Modern Library, 2012). I also discovered a newfound love of nonfiction. My two favorites were In the Dream House by Carmen Maria Machado (Graywolf, 2019), a memoir about Machado’s experience in an abusive relationship, and How to Be an Antiracist by Ibram X. Kendi (One World, 2019). Both books are wonderfully crafted and engaging until the very last page, and I firmly believe everyone would be better for reading them.

When lockdown hit, two friends and I created a virtual book club with the ambitious goal of reading a book a week. Not only did our weekly Zooms keep me sane, they also introduced me to some of my favorite books of the year: The Vanishing Half by Brit Bennett (Riverhead, 2020), Girl, Woman, Other by Bernardine Evaristo (Grove Press, 2019), Middlemarch by George Eliot, and Cloud Atlas by David Mitchell (Modern Library, 2012). I also discovered a newfound love of nonfiction. My two favorites were In the Dream House by Carmen Maria Machado (Graywolf, 2019), a memoir about Machado’s experience in an abusive relationship, and How to Be an Antiracist by Ibram X. Kendi (One World, 2019). Both books are wonderfully crafted and engaging until the very last page, and I firmly believe everyone would be better for reading them.

Rachel Ahearn, Advertising Designer

This year has been peculiarly weighted in favor of nonfiction. In addition to my usual diet of classic novels that I should have read in college but didn’t, I enjoyed a bunch of really wonderful discussions of history, philosophy, and art. Pantone: The Twentieth Century in Color by Leatrice Eiseman and Keith Recker (Chronicle Books, 2011) is an especially fascinating read, connecting colors and palettes to topics in history, including Art Deco architecture, anti-apartheid activism, and the origins of Pantone itself.

Some other highlights:

- Paper: Paging Through History by Mark Kurlansky (W. W. Norton, 2016)

- The Tibetan Book of the Dead (Penguin Classics, 2007)

- Words and Rules by Steven Pinker (Basic Books, illustrated edition, 2015)

- Art of the Book: Structure, Material and Technique (Gingko Press, 2015)

If you’re thinking of picking up any of our 2020 reads for yourself or a friend, be sure to support your local independent bookstore!

Published on December 17, 2020