Wellington

by Gregory O’Brien

Ninety percent of humanity lives in the northern hemisphere. There’s something reassuring, just now, in that fact. The southernmost lamppost on the planet is believed to be in the South Island town of Invercargill. Isolation has never looked so good.

At the east end of Lyall Bay, where waves come within fifty meters of the Wellington International Airport runway, there has for some years been a ban on kiteboarding—presumably to prevent the airborne cowboys of the south coast from colliding with the Qantas arrival from Sydney. For the last two months, however, nearly all the planes have been grounded. For kitesurfers, as for joggers on the beach, the fat black variable oystercatchers (torea tai) have become more of a hazard. Gaining in confidence over recent weeks, they now stride or glide wherever they choose, as if they own the place.

The lockdown has been good for avian life. I have never seen so many of these birds striding around a city beach or heard such an amiable racket. Kleep, kleep. With the global population of variable oystercatchers down to around 4,000, this endangered but evidently recovering species has lately proved, for those of us out walking, unexpectedly good and instructive company. For once, humanity and birdlife are wading the same waters.

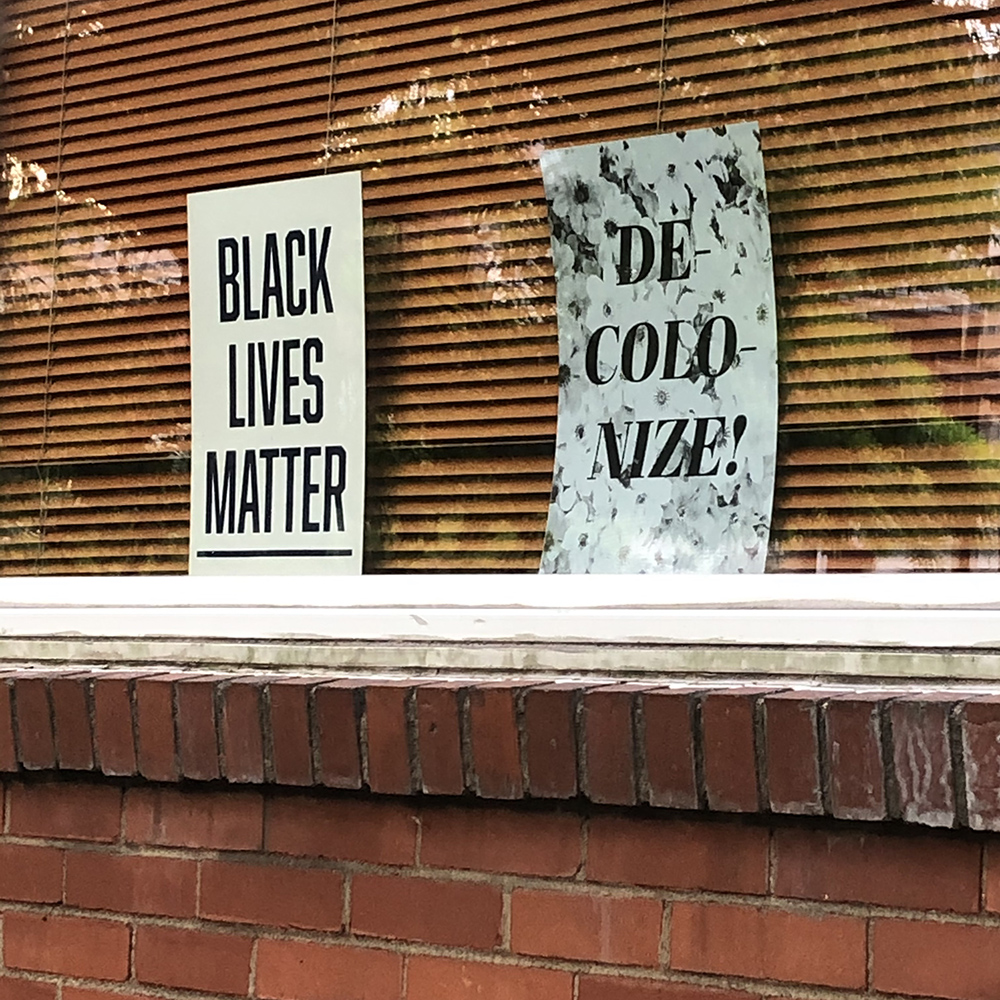

During the five weeks of near-total lockdown, the police were kept busy chasing surfers from beaches or ticketing them when they came ashore. Legitimate at last, the wetsuit-clad bodies now linger between waves like kelp. Under the sensible, cautious leadership of Jacinda Ardern, Aotearoa/New Zealand has weathered the present storm better than just about anywhere else, with the possible exception of a few Pacific islands. Our Rarotongan niece, who has spent the duration of the lockdown in our three-generational “bubble,” pronounces in a faux-triumphal tone: “There is no coronavirus on the Cook Islands!” And my Niuean artist friend John Puhiatau Pule, domiciled in Auckland, writes to say: “No COVID on Niue!”

With no direct social contact allowed at this point but some food outlets allowed to partially reopen, a takeaway store owner in Wellington has modified his cat-flap so that fish and chips can be delivered through it. Reluctantly, bicyclists and pedestrians are having to let cars back on to the city’s streets. Flat whites from Queen Sally’s Diamond Delicatessen, a stone’s throw from the oystercatchers, are handed out to us on the footpath—the best coffee in the universe, or so it seems when consumed with a salty Cook Strait breeze in your face, ruffling your unkempt head of hair. (Since hairdressers have been locked down, the average length of hair in the nation has increased alarmingly.)

Most of the writers and artists I know have been able to “keep calm and carry on” with relative ease. On a grimmer note, retailers are in trouble, tourism is “over, for now,” and the nation’s alcohol consumption has gone up twenty-four percent. Netflix is doing a brisk trade and bird-watching is also on the increase, as numerous native species have returned to streets and parks that were, for a time, near empty.

Across town, our son Carlo’s house has been regularly visited by fantails (piwakawaka), usually a shy bird, and rowdy, overfed wood pigeons (keruru) have been crashing around the puriri trees in the inner suburbs. Last week there was even a confirmed sighting of a rare New Zealand falcon (karearea), perched on a building high above Lambton Quay. Lingering in the collective mind of the nation, maybe that bird could be our emblem for the future. In the months and years ahead, as we reset the nation’s compass and recalibrate our relationship with each other and the environment, the karearea and other birds might be a tutelary presence.

Published on May 11, 2020