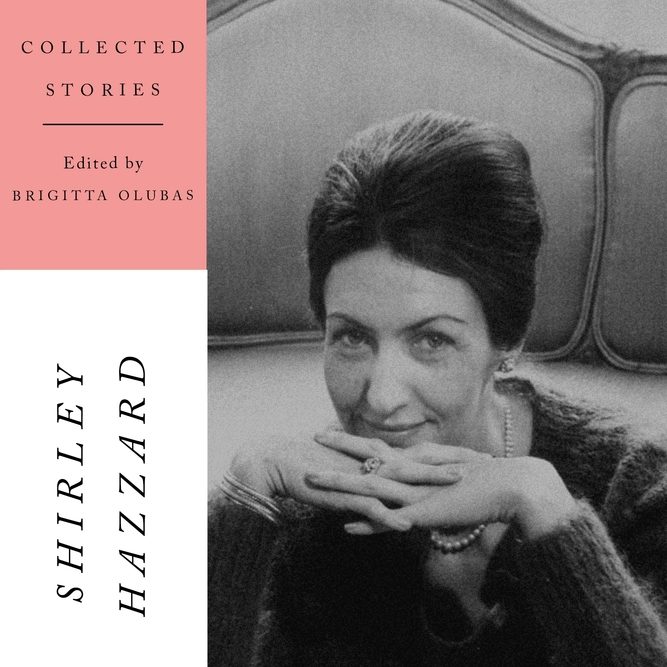

Collected Stories by Shirley Hazzard, ed. Brigitta Olubas (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2020)

Contributor Bio

Brigitta Olubas

Out of Step with the Modern World: The Making of Shirley Hazzard’s Collected Stories

Brigitta Olubas talks to Harvard Review

Shirley Hazzard (1931–2016) wrote nonfiction, short stories, and several novels, including The Great Fire, winner of the National Book Award. In this conversation with Harvard Review, Brigitta Olubas, professor of English at the University of New South Wales and the editor of Hazzard’s Collected Stories, sits down with Harvard Review to talk about Hazzard’s career, style, repeated “rediscovery” (she’s never really gone away), and those impeccably crafted sentences.

Harvard Review: Shirley Hazzard seems to be “having a moment.” To what do you attribute the resurgence of interest in her work?

Brigitta Olubas: I think much of the current interest stems from her recent death, in December 2016, which has led to wonderful tributes like Michelle de Kretser’s On Shirley Hazzard, as well as to the Collected Stories (and a biography, which is in progress). Not long before her death, her Selected Essays were published, and this also brought new readers to her work. Writers’ deaths allow, or prompt, readers and publishers to mark their achievement, to return to their work and reconsider it, and, of course, to republish it. All this brings new readers to the work.

What’s interesting in Shirley Hazzard’s case is that it has happened to her before. Her last novel, The Great Fire, was published twenty-three years after The Transit of Venus, and there had been a ten-year gap between that and the novel before. Both those publications were long awaited, and the publicity and reviews of both made a lot of that, so in both instances there were new generations of readers discovering a “new” writer.

Hazzard’s career was a long one, but with those long gaps as well; her work is not easily aligned to a particular period. This also might be part of its current appeal, the fact that her writing is not really datable, or that it seems to come to us from quite a different time from whenever “now” is. And this has been observed by readers throughout her career. Hazzard has never read very much like her contemporaries. And while the worlds she writes about are more or less contemporary and familiar, her concern with formality and morality and the power of art and of love, and her rather stately prose, have always seemed to refer back to earlier times. This is quite deliberate, of course. She felt herself in many respects out of step with the modern world and was deeply versed in the literature and art of the past, and she sought to pay tribute to the writing she loved in her own work. She wanted to keep those connections to past writers alive.

HR: Where do you situate Hazzard in contemporary arts and letters?

BO: I think that her place in the contemporary world is informed by her distance from it, that is, by her commitment to the past, and to the larger story of human being and art and learning and love. She wanted to find continuities across human experience, and she found these through a very particular devotion to reading and writing. This is far from a common or current view, and its appeal might lie in that distinctiveness. While she is admired, particularly by other writers, Shirley Hazzard is not as widely read as she might be. Perhaps the interest in her Collected Stories will encourage people to read her work.

HR: Hazzard was a distinguished short story writer and novelist who mostly stuck to novels later in life. Why?

BO: Like many novelists, Shirley Hazzard began by writing short stories, which were quickly picked up by the New Yorker, which began publishing her work from 1961. After her first collection, she published a novel—actually more a novella than novel—The Evening of the Holiday, which had begun as a series of interconnected stories that developed into a larger work. She continued writing and publishing short stories for another decade or so, and those stories became chapters of her longer novels, first The Transit of Venus and later The Great Fire. So there is a very particular connection between the forms of short story and novel for her, where the shorter form feeds into the longer.

Working this way seems to have allowed her a period of apprenticeship to develop her writing—remember, she was successful in getting published very quickly, without a long period during which to hone her skills and develop her style—but also the space to work through a scene or series of events or a group of characters outside the novel structure. This process of writing and publishing chapters from novels as stand-alone stories also relates to one of the many strengths of her writing: the depth and richness of the secondary characters and story lines. Almost all the stand-alone chapters published separately deal with secondary characters.

HR: What overlap and divergences do you see between Hazzard’s short and long fiction, her earlier and late work?

BO: In terms of early and late work, there are remarkable continuities across her oeuvre in terms of the quality of the writing—her early work reads like that of a mature writer, with a distinctive style, and then just gets better—but also some changes and development. Her two later novels are more philosophical. They are also larger and more layered and complex than the earlier. They are more ambitious in scope, and the style is more ornate.

But I think the germs of the narrative complexity of those later works, particularly Transit, which is her masterpiece, can be found in the earlier novels, which seem slighter and more restrained but which are built around some very complex plotting. The early novels look at first like light Anglo-Italian romances, but in both, romance is wound about with death and loss and delay and complication. So, in The Bay of Noon, the narrator tells us that she had come to Naples “because I was in love with my brother.” It’s a shocking statement, and one that doesn’t really go anywhere obvious in terms of the narrative. What it does is to alert us to the fact that we’re dealing with something more complex and interesting than a straightforward story about romantic love.

The other thing I’d say about the move from early to late work is that the style changes. Just as the story lines get more complex, so do the sentences. And, really, it is Shirley Hazzard’s sentences that her readers are here for. They are like no one else’s. I have written elsewhere of the unexpectedness of her sentences and the ways their leaps of sound and sense force readers to take the work of reading seriously. The two really important features of her style—its aphoristic and its allusive qualities—are most fully evident in the later novels.

HR: Hazzard lived all over and worked at the UN. What impact does internationalism have on her work?

BO: Shirley Hazzard was eloquent on the matter of internationalism, as a broader principle and also in terms of her own place in the world. She spent most of her life living between New York and Italy—she had homes in Manhattan, Naples, and Capri—saying that her temperament was “not a very national one” and that she felt it “a privilege to be at home in more than one place.” She was deeply committed to the spirit of international cooperation that developed in the wake of the Second World War. This was why she felt deeply betrayed by what she saw as the shortcomings of the UN and why she railed against nationalism in both the Australia of her birth and the US of her adult years.

Hazzard was a writer of political polemic, including two monographs on the United Nations and a number of essays and nonfiction pieces. While she felt that there was a tension between this kind of public writing and the novels—that the former was taking her away from the latter, which was more important—she still continued to produce both. This was because she took very seriously the role of the writer speaking truth to power, holding contemporary individuals and institutions to account.

HR: Do you consider Hazzard an “Australian writer,” an “American writer,” an “Anglophone writer”? Did these designations matter to her, or to our understanding of her?

BO: She has latterly been described as an Australian-American writer, which seems true in a literal sense. However, her work sits uneasily in both categories. Anglophone seems literally true, but it sits oddly as a reference point for a writer who was fluent in French and Italian (including in the Neapolitan and Caprese dialects—her Capri bookshelves included a copy of Shakespeare’s Tempest translated into Neapolitan).

HR: Finally, how did you first come to Hazzard? What has this project been like for you as a fan and as a scholar of Hazzard’s work?

BO: I published the first scholarly monograph on her work in 2012. I was astonished to find how little academic commentary there was on her work. This was surprising, particularly given how responsive the density and complexity of her work is to close scholarly reading. In 2010 I received a grant from the Australian Research Council to research her work, and this funded research for the monograph and also a symposium at Columbia University in 2012. I also co-organized a public event with the New York Society Library in 2012 to honor her. Hazzard attended this event and spoke, briefly and memorably. It was her last public appearance.

The Collected Stories of Shirley Hazzard, edited by Brigitta Olubas, is out now from Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Published on March 19, 2021