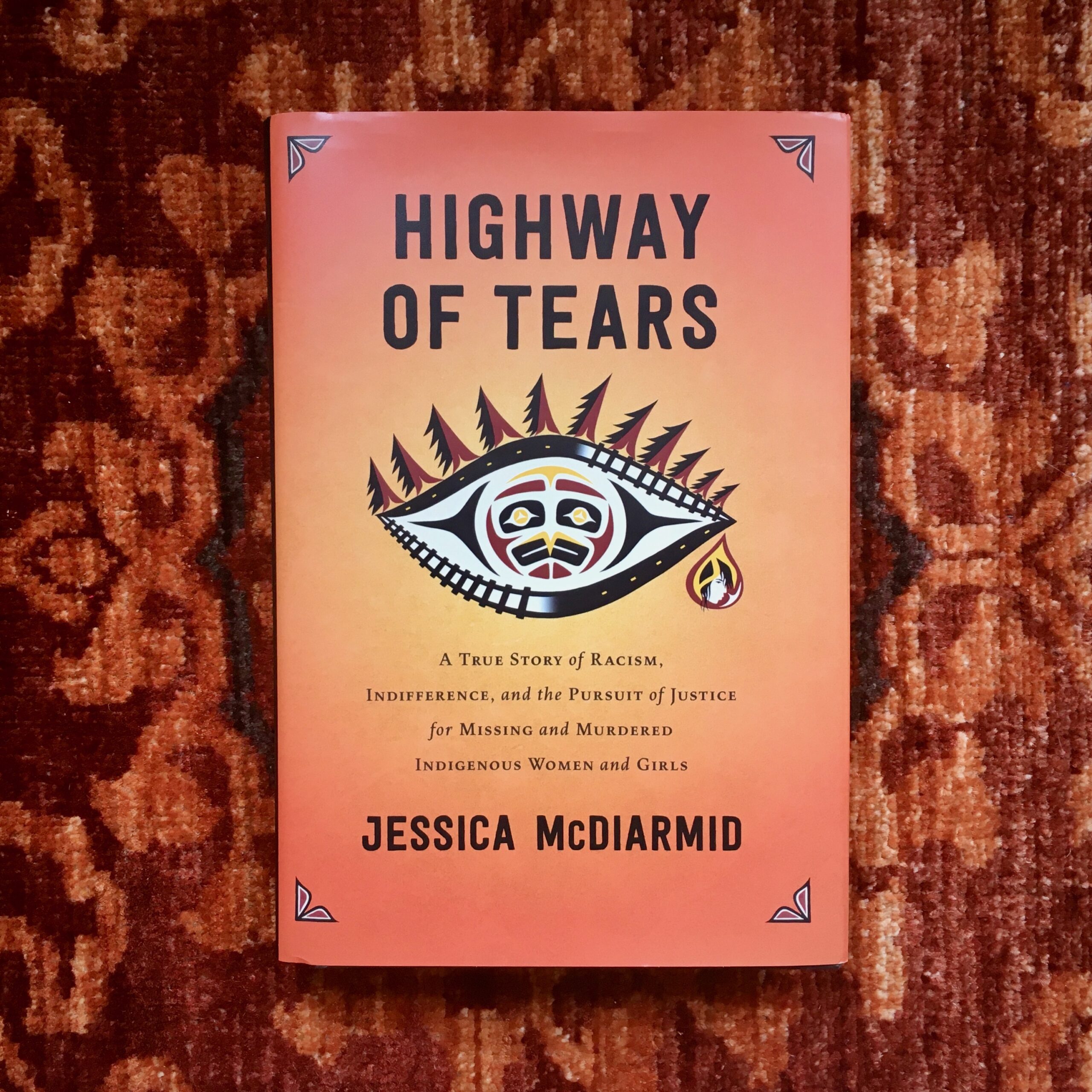

Highway of Tears cover art by Kym Gouchie

Contributor Bio

Jessica McDiarmid and Ophelia John

More Online by Jessica McDiarmid, Ophelia John

The Ethics of Investigation: An Interview with Jessica McDiarmid

by Ophelia John

Jessica McDiarmid’s work first appeared in Harvard Review Online with “A War Across the River.” Her first book, Highway of Tears, an investigation of missing and murdered Indigenous girls and women along a stretch of remote road in northern British Columbia, was a 2020 finalist for one of Canada’s biggest literary honors, the RBC Taylor Prize. In this interview with Ophelia John, McDiarmid considers her work as an investigative journalist and teller of individual stories.

Ophelia John: Writers of narrative nonfiction often appear as a character in their works. You’ve bucked this trend in Highway of Tears by appearing only in the introduction and the final chapters. Can you talk a bit about how you arrived at this narrator-not-in-the-story approach? Were your editors in agreement with it, or was this something that you had to advocate for?

Jessica McDiarmid: This was a story—or many stories, rather—about horrendous abuse, crime, injustice, and indifference. There was the kind of typical investigative journalism aspect of it, probing what happened to the missing and murdered individuals, and taking a hard look at the larger picture: how is it that such a sparsely populated region can see this many cases of girls and women disappearing? How is it that none of these cases has been solved? What have the police, the government, the public been doing to stop this?

The other aspect of it, which was deeply important to me, was telling the stories of the girls and women and their families. I didn’t want anyone to be lost in a statistic: this many missing, this many murdered. I wanted readers to really feel each one of these human beings. It was about honoring them and their families and elevating the voices that are so often silenced or ignored in our society.

The last thing I wanted to do was draw any attention away from these neglected stories and voices. The fact that I grew up there helped me immensely in my work, as I was familiar with the region, many of the people, and this story had been with me all my life. There were those who suggested a memoir of sorts about my experiences in the region, how this affected me growing up, something along those lines. But the suggestion that a book about a white girl’s experiences amid a genocide of Indigenous women and girls was somehow more compelling was, to me, an ugly demonstration of the very problem.

I did, however, think it was important to be transparent about my background in the region, my race, and my role in the events that take place in the book, such as the walks along the highway.

OJ: This is a deeply researched investigative work involving extensive fieldwork: digging through newspapers in local libraries, locating people who could lead you to other people, conducting repeated interviews in person. How did you gain the trust of your interviewees, given that you’re not a member of a First Nations community and that racism on the part of the police and other authorities has long been a critical problem in northern BC?

JM: The most important aspect of this book—the process and the result—was that it do no further harm to the families. Many families who have lost loved ones to violent or unexpected events will tell you that the media adds another layer of trauma to an already horrendous experience: both the process of gathering the news—hounding families, staking out homes, etc.—and how these events are reported, using victim-blaming language or focusing on a victim’s, say, criminal history or lifestyle. Other Highway of Tears families had a different experience: that of being completely ignored. I found a letter to the editor in a local newspaper where a mother with a missing daughter is literally begging for anyone—reporters, police, anyone—to do something.

So I expected a lot of justifiable mistrust.

I already knew some of the key people and had been discussing the idea of a book with them for years. That helped. I approached the Highway of Tears Initiative, a First Nations-led program that has worked on making the highway safer, and explained my idea. The coordinator at that time was Brenda Wilson, whose sixteen-year-old sister, Ramona, was murdered in 1994 in Smithers, the town where we all grew up, though we didn’t know each other as young people. Brenda invited me to join the 2016 walk along the highway, a three-week journey where we stopped in all the communities along the way to share stories of lost loved ones. I met many of the families along that walk and was able to tell them about the book and invite them to participate. I didn’t demand immediate responses or push anyone; I just got to know people and communities.

Over the next couple of years, most of the families agreed to share their stories and be part of the project. Some I hadn’t met reached out, wanting their stories and loved ones included. No one said they didn’t want the book done, and no one refused to take part. I like to think that the families trusted me because I earned their trust.

I also took another unusual step for a journalist in offering to share the parts of the book pertaining to each family before publication. It was really important to me that I didn’t publish anything that would further hurt these people. I was worried that people might have shared things with me as a person rather than a journalist, and I also wanted to ensure that I wasn’t inadvertently perpetuating colonial attitudes, stereotypes, assumptions. I was writing about communities and cultures and history that I was only just learning about, and I didn’t want my ignorance to do harm. I was somewhat surprised that no one asked for more than tiny changes. The courage of these families astounds me, and being trusted with their stories is the honor of a lifetime.

OJ: In developing this book, when did you become certain of its driving theme—that these murders are effectively human rights abuses and that we are all complicit? As the book explains, an Indigenous woman is six to seven times more likely to be murdered than a white woman. Did you arrive at this “big idea” after starting the research, or was it part of your original concept?

JM: I was aware from the start that there was a vast difference in both the societal and the official response to crime depending on the victim. As Kristal Grenkie, a white woman who was best friends with one of the victims, told me, her behavior was far more risky than that of Ramona Wilson, who was murdered. But, like me, she felt that she was protected by her race. A potential perpetrator would know that plucking a white girl whose mother was a respected businessperson off the street would draw a hell of a response. Targeting Indigenous girls and women almost guaranteed impunity.

What I didn’t know was the deep underlying reasons for this ugly reality. The circumstances and attitudes that make Indigenous women and girls so vulnerable are the result of five hundred years of colonialism, of European, Christian, patriarchal values and mores, and of government policies like residential schools. I had always thought of Canada as a pretty decent, humane country; that was certainly what we were taught by the school curriculum growing up, and it’s a view widely espoused around the world.

I’m embarrassed to say now that, after returning from a few years working in West Africa and learning a lot about colonialism there, I was shocked to hear an Indigenous leader describe Canada and the horror of the epidemic of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls here as a result of colonialism. I had spent years immersed in understanding the horror of colonialism, and yet I had never realized it applied as much to my own country as to those far away. It was not a comfortable thing to be disavowed of my notions about Canada, but that discomfort pales in comparison to the suffering of others in this colonial country.

OJ: You illustrate how police work and media coverage are hugely influenced by the concept of an “innocent” female victim. Some (but not all) of the girls disappeared while hitchhiking; their families couldn’t afford cars, and they still needed to get to work and school. What was your thinking when it comes to negotiating the class divide (given that many readers won’t have personal experience with rural poverty) and the “innocent victim” concept?

JM: I hoped that focusing on the stories of the girls and women and their families would help bridge the gap in understanding, and that bringing readers into their lives and communities would teach them some of the reality of poverty, racism, and lack of opportunity. Even in this region, there are so many people who don’t understand this reality because they themselves don’t live it and they don’t know anyone who does.

For example, hitchhiking isn’t a choice for many people. In the winter of 2019, I was driving home to Smithers from Prince George—a four-hour drive—and came across a tiny figure hitchhiking on the side of the highway. It was dark, snowing, and really cold, about -12 degrees Celsius. I stopped. It was a woman in her 70s who had been in Prince George for a medical appointment. It had run late and she had missed the last public bus that would have got her home, a two-hour drive away. That’s the kind of situation people find themselves in.

The vulnerability goes beyond hitchhiking, though. It comes from a lot of factors: racism, the pervasive impunity with which violence is perpetrated against Indigenous people, families grappling with the trauma of residential schools, the child welfare system, the near-crushing of Indigenous culture and language, the lack of trust in police and authorities. To chalk it all up to hitchhiking, as many do, oversimplifies a complex set of circumstances.

Published on September 17, 2020