The Body Keeps the War

by Acree Graham Macam

Genealogy is one of those hobbies I’d like to have if I were the kind of person who had hobbies. So when, on a slow work day, I receive an email from FamilySearch, a crowdsourced genealogy website where I keep my family tree, I open it.

“A new document was added to your great-grandfather’s page!”

I am in my third trimester of pregnancy, sitting on the couch with my feet up. My ancestor’s name looks back at me in bold blue type, and I shift the laptop to make room for my belly. According to family lore, my great-grandfather became addicted to morphine as a medic in World War I, and my great-grandmother left him, taking their children to be raised by another man whose initial decorates the silver I inherited. I haven’t thought about my biological great-grandfather in ages. We don’t hate him; we just don’t think about him. We’ve kept his name but speak of him rarely. He is a skeleton in the closet, an interesting story told in low voices over glasses of wine, a no-good, long-dead louse.

Speaking of lice, they apparently plagued soldiers in World War I. I learned this reading Erich Maria Remarque’s 1929 classic, All Quiet on the Western Front. Growing up, it was one of those titles that popped up on book report lists, but it sounded like a boy book, filled with battles and maybe cowboys, nothing like the Jane Austen novels I devoured as a teen. Then, last year, Netflix produced a movie adaptation that was nominated for Best Picture and one of my favorite podcasts covered it. I read it, and now there’s this email.

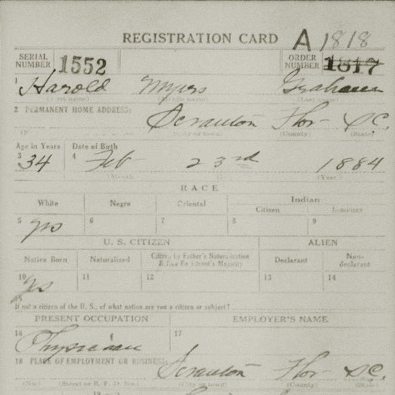

I feel the fetus stir as I open the document from FamilySearch. It’s the louse’s World War I draft registration card. I’d always assumed he entered the war willingly. Was there even a draft in World War I?

There was. A month after the US entered the war in May 1917, Woodrow Wilson and Congress passed the Selective Service Act, requiring every American male between twenty-one and thirty-one to register for possible conscription. A year later, when they ran out of bodies to send to the front, they widened the range to eighteen to forty-five. My great-grandfather registered on September 12, 1918, at the age of thirty-four. On his draft card he is described as tall and slender like my grandfather, who played basketball.

I am thirty-seven now. I have children and a spouse and a career just like the louse. I’m too tired to go out past eight o’clock. Instead, I stay in and watch true crime documentaries while folding laundry and laughing at memes on my phone about how millennials hate to leave the house. I imagine my great-grandfather had similar mid-thirties proclivities. I imagine he loved to settle into an armchair with a book and a brandy before turning in to bed. Too bad, his draft card said. It’s time for war.

The Selective Service Act changed how America went to war. Draftees comprised 70 percent of the American military in World War I, as opposed to just eight percent in the Civil War. In the summer of 1918, ten thousand Americans a day began arriving at the Western Front, the battleline in Europe where much of the fighting took place.

On the opposite side of the conflict, Paul, the protagonist of All Quiet on the Western Front, volunteers for the war effort. He is just nineteen, a German schoolboy bowing to patriotism, propaganda, and the persuasion of trusted adults. Yet, by the time we meet him, he is already hardened by war. “We have become wild beasts,” he says. “We do not fight, we defend ourselves against annihilation …. If your own father came over with them you would not hesitate to fling a bomb into him.” When I google “trench warfare,” I see words like “grueling,” “hellish,” and “futility.”

Hungry for more details about my great-grandfather, I search for him in every online archive with a free trial. I find him in the 1930 census, listed as a member of his sister’s household and a veteran of the First World War. He is marked “M” for married, but his wife and children are already gone. Gone, too, are any further records of his military service, possibly due to a 1973 records fire. But I learn that, as a doctor in the war, he would have treated the common ailments of trench warfare in a world before antibiotics: not just combat injuries, but pneumonia, influenza (including the 1918 flu), dysentery, tuberculosis, typhus, infections, and lice. Conditions at the front were so bad that troops had to be rotated out of the trenches every week or two just to keep them in fighting condition. If you were a soldier in World War I, you were more likely to be killed by disease than by the enemy.

Remarque is unforgiving in his portrayal of doctors at the front, describing surgeons who will operate and amputate “on the slightest provocation.” “There may be good doctors,” he writes, “and there are, lots of them; all the same, every soldier some time during his hundreds of inspections falls into the clutches of one of these countless hero-grabbers who pride themselves on changing as many C3’s and B3’s as possible into A1’s.”

I wonder if my great-grandfather was one of the “good doctors” or if he was a “hero-grabber,” not so much healing men as patching them up to ship them back to the front. I wonder if he stole morphine from wounded soldiers. I’d like to think he only took what wasn’t needed, and yet, in this war, everything would have been needed.

They called it a “war of attrition.” History is full of euphemisms like this: “troops” instead of “people”; “conscripted” instead of “forced to fight”; “war of attrition” instead of “the side that supplies the most dead bodies wins.” With millions of soldiers dying, people were a finite resource, like food, medicine, gauze, and gas. When fresh recruits from the enlistment rolls replenish Paul’s depleted unit, he describes them as “anemic boys in need of rest, who cannot carry a pack, but merely know how to die by thousands.” His friend Kat remarks, “Germany ought to be empty soon.”

I keep googling the cause of World War I. I read paragraphs and paragraphs, the words washing over me like shrapnel over trenches, like amniotic fluid over the human I am creating. They seem so logical on the page, but when I close the browser, I can’t recall their meaning. Of all the big wars, this one makes the least sense to me, perhaps because American memory has failed to construct a sticky metanarrative around it. In the Revolutionary War, we won our independence from Britain. In the Civil War, we tested the unity of the nation. In World War II, we vanquished the Nazis. In the Vietnam War, we fought—and failed—against communism. World War I is defined by what it preceded. Even at the time, it seems, the war struggled to explain itself. I come across a propaganda pamphlet entitled, “Why America Fights Germany.” It is sixteen pages long.

Paul and his friends pose the same questions I do. During a rest period, one of them asks,

“What exactly is the war for?”

Kat shrugs his shoulders. “There must be some people to whom the war is useful.”

“Well, I’m not one of them,” grins Tjaden.

“Not you, nor anybody else here.”

“Who are they then?” persists Tjaden. “It isn’t any use to the Kaiser either. He has everything he can want already.”

“I’m not so sure about that,” contradicts Kat, “he has not had a war up till now. And every full-grown emperor requires at least one war, otherwise he wouldn’t become famous. You look in your school books.”

Kat, older than the others, is poor and powerless, but he’s no fool. He’s aware of his own role—small yet significant—in the larger story. Without cannon fodder like him, how would history’s great men gain immortality?

Here’s another euphemism for you. When my uncle (grandson of the louse) died, my dad told me he’d had an allergic reaction to some medicine. Or maybe that’s how I interpreted my father’s explanation at age eight, and he never corrected me. But every family has someone who lets the skeletons out of the closet, and when I was a teenager my mother told me about my great-grandfather’s addiction and divorce. She also told me that my dad’s brother’s death had been drug-related. Yeah, I said, like an allergic reaction to a medicine. No, she said. More like a heroin overdose.

Years later, I would connect the dots between the morphine addict and the heroin addict. The realization would come long after the autopsy of my father’s body came back with the words “methadone toxicity,” even after I learned the word “opioid” and realized all these drugs were, in essence, the same. When the connection finally hit me, it seemed to be the answer to a riddle: Three men, two generations apart, their lives taken by the same substance.

My father died in 2008, when the nation was in the midst of an opioid crisis, but no one knew that yet, or at least, no one I knew. My father lived hundreds of miles from the Rust Belt and other regions typically associated with the crisis in a house tucked back in the woods in Cary, North Carolina. He had suffered from arthritis for decades. The bones of his knees made popping noises as they carried him up the stairs to say goodnight. He’d stub his toe on a chair and roar. He was diagnosed with fibromyalgia and put on Oxycontin. I was told never to touch his pills. Never, ever. I was told not to tell friends we had them. I was told just one could sell for hundreds on the street.

On the drug, my father became loopy and disoriented at night. Then—famously hot-tempered, with a quick tongue—he got into a verbal altercation with a younger man at a car wash, and the man shoved him. My dad had to have part of his spine removed.

“My doctor’s trying to get me off Oxycontin,” he told me. The doctor was both a medical doctor and a psychiatrist. Seeing that my father was becoming chemically addicted to the drug, he wanted to combine the pharmaceutical regimen with massage, swimming, and talk therapy. Eventually, he switched the Oxycontin to methadone, which is often administered at hospitals to help heroin addicts withdraw safely. My father was given pills, and my stepmother kept them in a box under lock and key.

By that point, my father’s loopiness had drifted into the daytime. Once, near the end of his life, I was leaving his house after dinner when he asked me, “Are you going to see your dad when you go up to Virginia?”

He meant my grandfather. “You’re my dad,” I said, frustrated and sad.

“No, I’m not,” he said. He was out of his mind.

I got in the car and left.

When Paul attacks a Frenchman and ends up stuck in a shell hole for hours with the dying man, he refers to his former kills as an “abstraction.” The ten million people who died in the First World War are an abstraction to me, just like those who died in the Iraq War, or, more recently, in Gaza. The hundreds of thousands of Americans killed by the opioid crisis are also an abstraction, unless one of them is your father. The most heinous injustices around the world are all abstractions, until they’re not.

Patrick Radden Keefe’s 2021 book, Empire of Pain, exposes how Purdue Pharma and the Sackler family did everything in their power, including interfering with the FDA, to ensure Oxycontin maintained its sales, even as it became painfully clear that it was killing people by the thousands. “The opioid epidemic,” we call it, as if it were an unfortunate, unavoidable accident; like a war of attrition, the opioid crisis treats everyday people as collateral damage. Even now, we turn not to the justice system to correct the problems caused by the Sackler dynasty but to Narcan, the over-the-counter antidote to opioid overdose. We fight Big Pharma with more Big Pharma.

Face to face in the shell hole, the dying Frenchman becomes quite real to Paul. Moved to sympathy, he tries to comfort the man in his final hours, even calling him “comrade,” a term previously reserved for his fellow soldiers and friends. The real enemy, Paul suggests, is not the foot soldiers like him in the trench across the way, but the war itself and the people who started it. He vows to fight against the forces that brought them both there, but once he escapes the shell hole his resolve fades and it’s back to business as usual. Probably for the best. Acknowledging the absurdity of war will kill you if you let it.

Part of what makes All Quiet different from other war stories is that it’s told from the point of view of the losing side. In a typical story, a character with agency acts on their world, leaping over obstacles and ultimately undergoing a significant personal transformation. While the characters in All Quiet steal geese from French farmers and outsmart rats in the trenches, they also die suddenly and randomly, eroding the reader’s sense of cause and effect. The protagonist, Paul, is no hero. He does not overcome adversity or defeat death because adversity cannot be overcome, death cannot be defeated. Of course, this novel is told by the losing side: no one wins a war.

As the novel ends, the war ends also with the report, “All quiet on the Western Front.” The phrase suggests not peace, exactly, but armistice. It also suggests death. Like the lives of my father and uncle and great-grandfather, the war is not complete; it’s simply over. “Casualties,” we call the victims of war. The word comes from middle English, meaning a “chance occurrence.” These deaths couldn’t be helped. Nothing could have been done.

I’m lucky. As instructed, I never touched my father’s pills. I never wanted to. I was prescribed Vicodin once after getting my wisdom teeth out and flushed it down the toilet. I love cocktails and wine and have been known to ingest too many margaritas on a Tuesday night and pay for it on Wednesday morning. But I’ve also never been called to war or had to live with chronic pain. My grandfather and I were spared the addiction that plagued our fathers, which makes me wonder, superstitiously, if it skips a generation. I touch my fingertips to my pregnant belly as if to catch the not-yet baby about to burst forth into this world. I wonder what genetic sleeping giant might already be stirring in her body and what perfectly legal violence could wake it up.

Published on May 30, 2024