Suva, Fiji

by Sudesh Mishra

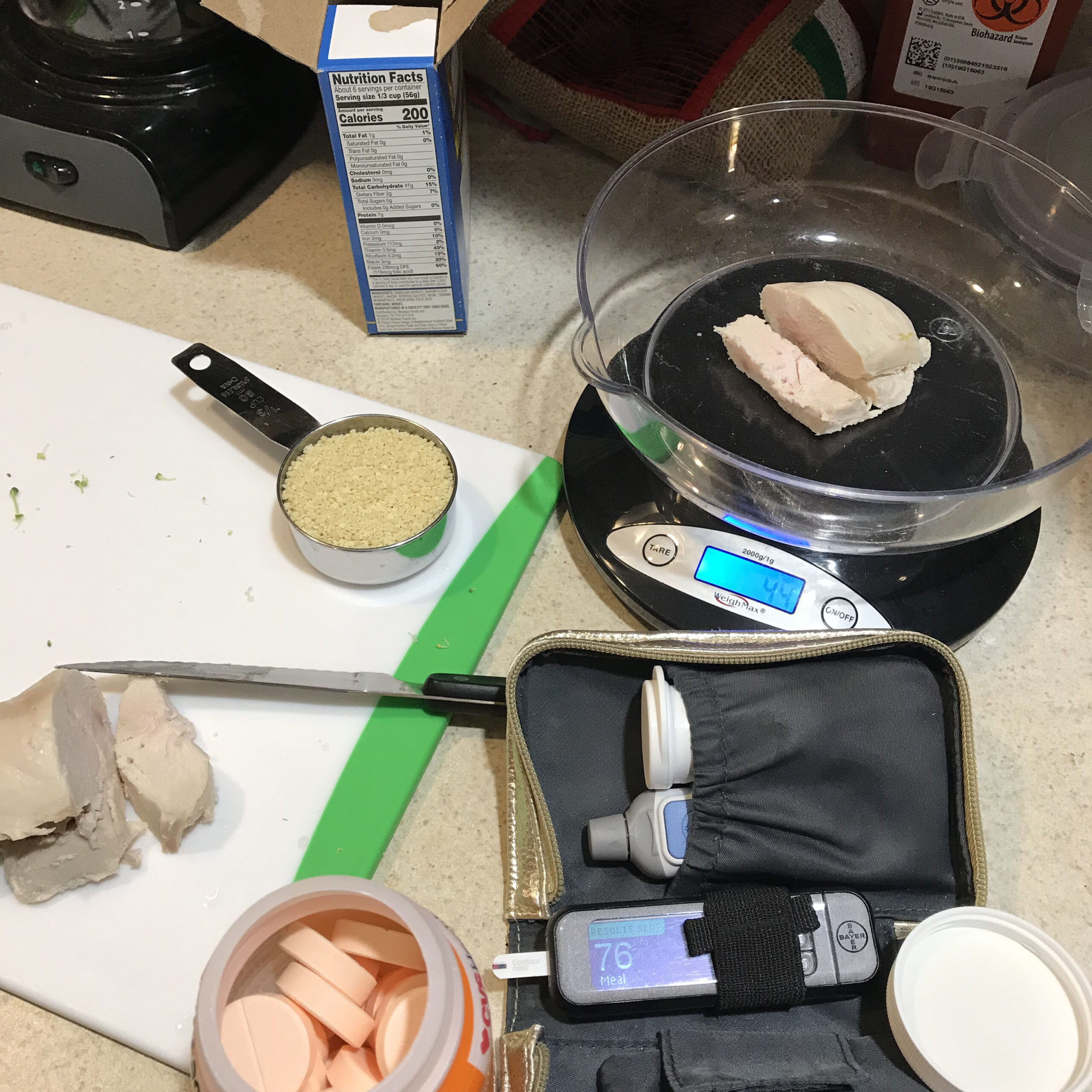

The day the city went into lockdown, we were locked out. We have a house on the outskirts of Suva, overlooking a green bay fringed by mountains the hue of olives. We are fond of olives, having cultivated a taste for them abroad, but we are cut off from the grocers that stock them. Cut off, that is, from Europe. So, we turn to our childhood staples, all grown locally and sold casually by the roadside: dalo, raurau, duruka (which is now in season) and okra. We curry the duruka in coconut milk and watch the flying foxes peel off their trees like brolly shreds in a storm.

A mad-eyed cyclone is whirling towards us from the north, from Vanuatu. It skirts around the main island, but a preternatural gust sends a great tree toppling across the driveway. When the curfew lifts at daybreak, I take a machete to the fallen tree. It’s a lovely tree, indigenous to these islands, but I haven’t had that thought in a while. I hack off a few branches when a vanload of policemen, armed with an orange chainsaw, offer to lend me a hand. A hand—hands. I have grown increasingly distrustful of my hands. Are they for me or against me?

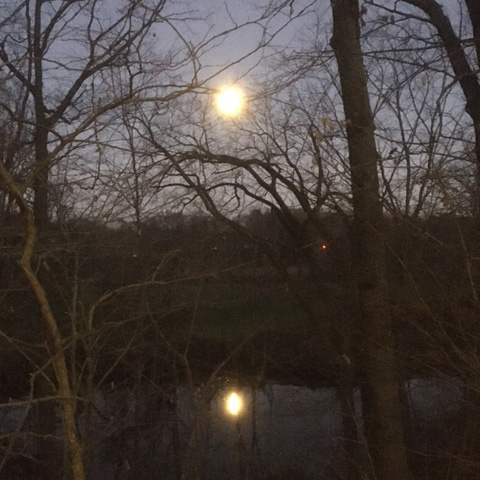

My wife doesn’t wait for an answer; she drowns them in alcohol, while I moon about the house, smelling of bad gin. We haven’t seen the moon for ages, I report to my daughter. When Melbourne University shut down, she joined her cousins in Brisbane. The weather has been dirty, I add. She’s learning to ride a bicycle, she says, as if the two ideas are linked. When, a few days later, the moon swings a fishhook in the sky, we gather at the window in wonderment. Is the renewed capacity for wonder a virtue?

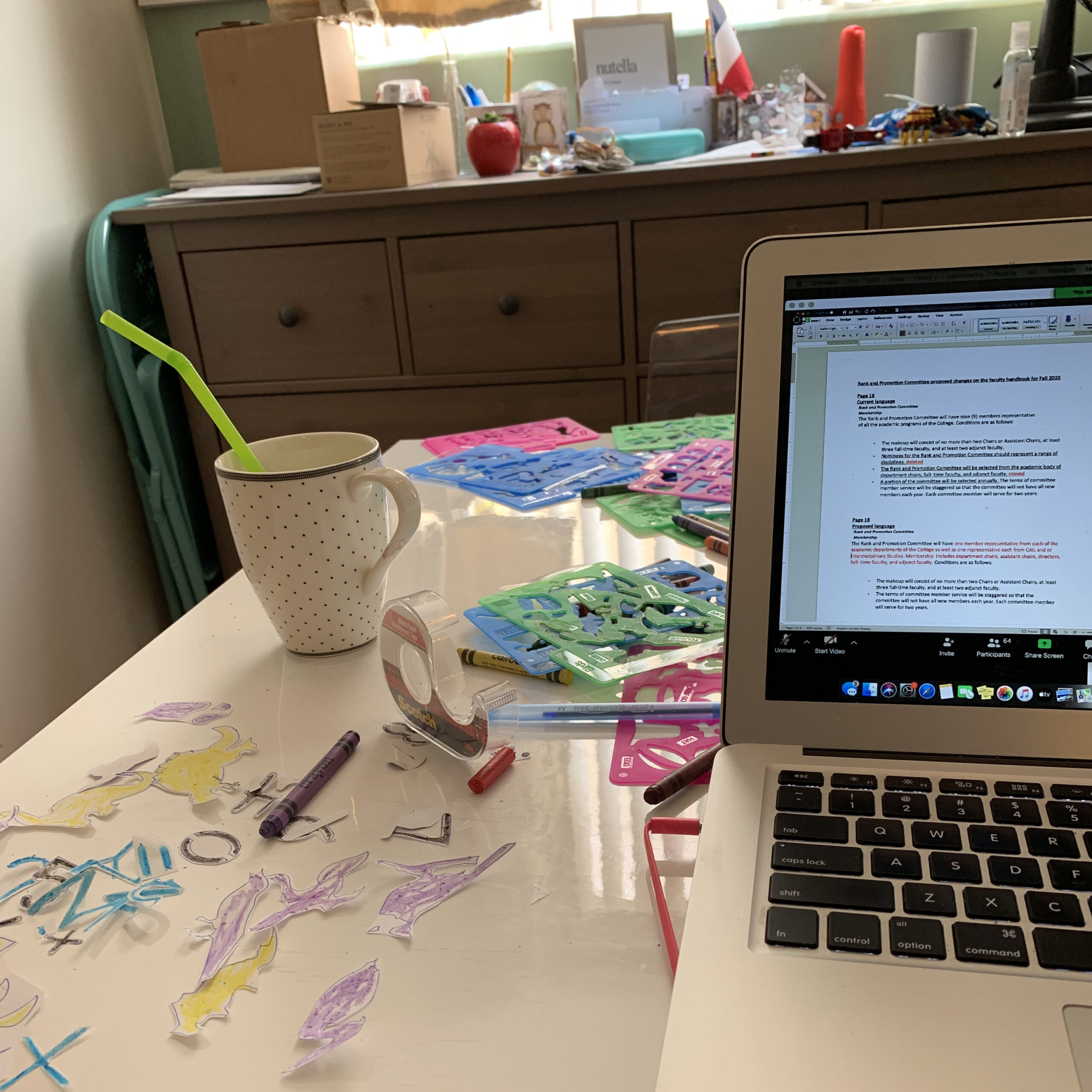

In a crisis we revisit the obvious because the obvious has become puzzling. I am no longer able to take my hands for granted. Taking things for granted is a perennial human flaw. We stare into the abyss of extinction, and yet we take things for granted. I wonder at the moon, at my hands, at uncertainty. They puzzle me and I am delighted. I am delighted with our younger child who has turned into an enigma. Whenever food tastes odd, she says it tastes familiar. Familiar days, too, have become familiar. Tomorrow, if they lift the curfew, we’ll drive along a familiar road to a familiar childhood street in Nadi. We’ll stay the night with my mother who, too, has become familiar. On the way back, we’ll swim in a familiar sea, fly a familiar kite, and praise life for its boundless familiarity.

Published on May 25, 2020