Kimiko Hahn, photo by Beowulf Sheehan

Contributor Bio

Kimiko Hahn and Ruben Quesada

More Online by Kimiko Hahn, Ruben Quesada

Object Lessons: An Interview with Kimiko Hahn

by Ruben Quesada

Kimiko Hahn is one of the first poets I met as a young writer. We creative writing students were invited to have dinner with the visiting writers, including Kimiko and her husband, Harold Schecter. I remember thinking that if ever there was an ideal relationship for a writer, it was this one: a poet married to an expert on serial killers.

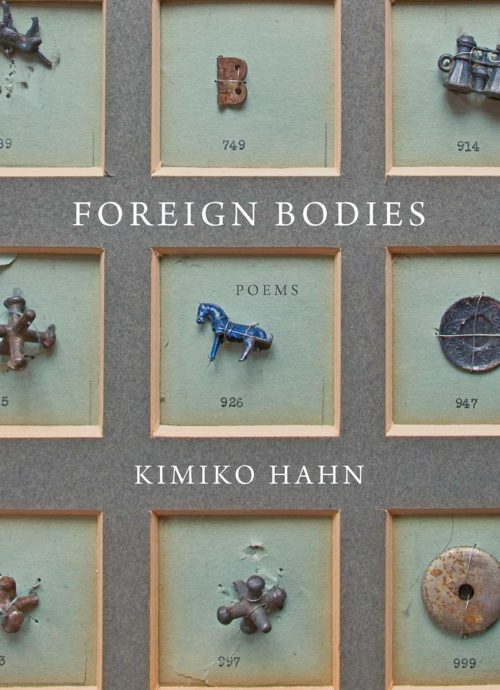

This interview was conducted via email in early 2021. In these exchanges, Hahn discusses her lifelong interest in macabre objects and fairy tales, how her newest collection, Foreign Bodies, took shape, and how to cultivate a poetic voice.

Ruben Quesada: The speaker of your most recent collection, Foreign Bodies, delves into a journey of mythological proportions. The object lessons that follow are mindful and evenhanded. Some reviewers have focused on the grief that inhabits these poems.

Kimiko Hahn: In the past ten-plus years, as I was writing new poems, my father was on the decline. My sister and I had to begin to deal with his hoarding. I began to write more personal poems (“The Ashes,” “A Dusting,” “Constant Objection”) and to think about mortality and also about his house full of stuff. After these newer poems, I returned to poems written after Brain Fever came out, poems that were not quite working. With a new vision of what I wanted to do—thematically and aesthetically—I revised “Object Lessons” and “Cryptic Chamber.” When a collection began to take shape, I looked to see what might be missing as far as subject and I saw that I hadn’t attended to my deep feelings for social justice. So I put more thought into the literal “foreign body,” whether a sex worker or my grandmother’s body. I don’t usually set out to write a “project book”—more, my obsessions over a few years emerge in my drafts.

Kimiko Hahn: In the past ten-plus years, as I was writing new poems, my father was on the decline. My sister and I had to begin to deal with his hoarding. I began to write more personal poems (“The Ashes,” “A Dusting,” “Constant Objection”) and to think about mortality and also about his house full of stuff. After these newer poems, I returned to poems written after Brain Fever came out, poems that were not quite working. With a new vision of what I wanted to do—thematically and aesthetically—I revised “Object Lessons” and “Cryptic Chamber.” When a collection began to take shape, I looked to see what might be missing as far as subject and I saw that I hadn’t attended to my deep feelings for social justice. So I put more thought into the literal “foreign body,” whether a sex worker or my grandmother’s body. I don’t usually set out to write a “project book”—more, my obsessions over a few years emerge in my drafts.

RQ: The opening poem, “Unearthly Delights”—a nod to Hieronymus Bosch’s painting “The Garden of Earthly Delights”—is full of foreboding. Bosch’s triptych depicts what has been called the whole of the human experience, from Genesis to Revelation. This poem is similarly full of

[ … ] tiny white naked human creatures

flipped topsy-turvy to skewer

down the ass and out the mouth

in the primordial ooze that is manifestly

the brimstone and bile of this book [ … ]

What kind of tone were you hoping to set with this opening?

KH: I’d been asked to write a poem for an anthology on Bosch’s work and, again, obsessions being what they are, this poem sprang up. I realized it was a good portal to the subjects of the collection. I was hoping the tone would be—yes!—foreboding.

RQ: In an interview with Lisa Higgs at The Adroit Journal, you mentioned the influence of the early-twentieth-century Imagist movement on your work, specifically William Carlos Williams’s admonishment: “No ideas but in things.” This collection is full of things and many types of bodies, most of them terrifying. It reminded me of a recent visit I made to the Museum of Death in New Orleans. The museum was full of artifacts—photographs, correspondence, clothing, surgical equipment—belonging to the dead and to murderers. It was macabre. The endnotes of Foreign Bodies indicate that you researched scientific and criminal documents, with headlines like “In Home Village of Girl Who Died in U.S. Custody, Poverty Drives Migration” and “The Case of Jane Doe Ponytail.” What led you to use such documents for your poems?

KH: “Terrifying,” yes. My parents were both visual artists and their collections (what became part of my father’s hoarding) often had an ominous aspect. My father’s paintings also reflected his interest in the shadow side of the psyche: paintings of a woman dancing with a skeleton, Medusa, Adam and Eve with the snake. And my mother repeatedly indulged me by rereading my favorite Grimm’s fairy tales (“Hansel and Gretel” and “Rapunzel”). This was my childhood world—one that some might view as macabre.

Fast-forward to my husband, who is a true crime writer, so all his forty-plus books have to do with death, mostly serial murder. We’ve visited that museum in New Orleans and of course the Mutter Museum in Philadelphia. Nearly every trip or vacation includes a cemetery or a gallery with elegiac paintings. The terrifying is one interest that we have in common—also, an abiding interest in folk and fairy tales.

I am drawn to captivating current events. Captivating for language, imagery, subject matter. It’s also true that at times I research. I’ll find something that nicks my curiosity and dive in, muck around. For those two articles, the material came to me. I wanted to think about the foreign body in different lights and seeing these articles triggered the poems.

RQ: “Unearthly Delights” also made me think of the opening poem of Lucila Perillo’s On the Spectrum of Possible Deaths, “The Second Slaughter.” That poem taught me about the possibilities of (re)inventing myths, about world-building, about thematic arcs in collections. What poem or collection of poetry has had an impact on you?

KH: In third grade, the poems of Edgar Allan Poe. In high school, Gertrude Stein and Lawrence Ferlinghetti. In college, Williams’s “Asphodel.” But impact? There’s a forthcoming documentary on Marvin Gaye and so the song “Mercy Mercy Me (The Ecology)” has been on my mind. I was in high school and lines such as “Fish full of mercury” were so radical to my ear and sensibility. I didn’t know you could use language or imagery like that in lyrics and poetry. This was 1971, a heady time of social unrest. I was a changed person. When I hear the song, I am suddenly, again, distraught and inspired.

RQ: What advice would you give to poets about finding their voice?

KH: Most writers suggest reading a lot, and it is essential to see what has gone before us and begin to pick up influences, likes, and dislikes. I’ll add to that admonition: read aloud. One can’t feel the totality of a poem without feeling it resonate in the body, without feeling the direct and subtle kinds of repetition, without hearing it. And one should read one’s own drafts aloud. Because we study literature in the classroom, it’s easy to think that poetry is about interpretation, about using the brain. But poetry is for the whole body. We need to bring the whole body back into the experience of art. When we use the word “voice,” we mean poetic voice, one’s own style and sensibility. But, after all, voice is vocal.

RQ: I am fascinated by writers and the lives they live. I started our interview with the impression I had when we first met decades ago, which admittedly is an idealization, but I am still an idealist in many ways. Will you share something that a reader would be surprised to know about you?

KH: That’s a funny question because I think of myself as that “open book.” But because very few people know my early work, a reader might be surprised to learn of my early grounding in Marxism. In my twenties, I led study circles on the Manifesto of the Communist Party. And it still makes sense: “[The worker] becomes an appendage of the machine, and it is only the simple, most monotonous, and most easily acquired knack, that is required of him. Hence, the cost of production of a workman is restricted, almost entirely, to the means of subsistence that he requires for maintenance, and for the propagation of his race. But the price of a commodity … ” It’s quite an elegant text.

Kimiko Hahn’s Foreign Bodies is available from W.W. Norton now.

Published on August 25, 2021