Mid-Century Modern: Conversations with 20th-Century American Poets

an interview with Chard deNiord

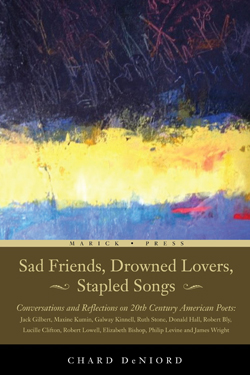

Chard deNiord talks about his interviews with some of America’s best-loved poets of the mid-twentieth century. The book is called Sad Friends, Drowned Lovers, Stapled Songs, Conversations and Reflections on 20th Century American Poets (Marick Press, 2011).

What prompted you to write this book?

About five years ago, I started interviewing poets who were born in the teens and twenties of the last century—poets who belonged to the World War II generation. They included Galway Kinnell, Ruth Stone, Donald Hall, Maxine Kumin, Jack Gilbert, Lucille Clifton, and Robert Bly. In my introduction I describe them as survivors of the Great Depression and World War II who felt enormously empowered by the time they started publishing in the mid and late 1950s.

None of my subjects, except for Robert Bly and Philip Levine, attended MFA programs. Only a few—Galway Kinnell, James Wright, and Philip Levine—became full-time tenured professors. The rest chose to teach intermittently while undertaking other vocations, such as freelance-writing (Donald Hall), horse-training (Maxine Kumin), and founding movements and literary magazines (Robert Bly). As a poet myself and great admirer of my subjects’ audacious generation, I was intensely curious about the provenance of these poets’ ground-breaking, subversive voices, as well as hopeful about learning invaluable lessons about life and poetry, in that order, from each of them as unique “courage teachers.”

What is it that unites poets of this period?

In the American boom years after the war, these poets wrote with a contagious subversiveness that compelled them to find their own new forms and subject matter—what Robert Bly in 1958 called “the new imagination”—in the face of such national and cultural blights as McCarthyism, aesthetic jingoism, paternalism, racism, the Vietnam War, and gender discrimination. Each poet responded by divining new language, strategies, and voices that testified to the strength of their genius, as well as to their chutzpah in believing that they could make something new in the wake of their formidable Modernist predecessors.

New blood streamed through their groundbreaking books in the 1960s and 70s: Galway Kinnell’s What a Kingdom It Was (1960), Robert Bly’s Silence in the Snowy Fields (1962), Maxine Kumin’s Up Country (1973), Jack Gilbert’s Views of Jeopardy (1962), Ruth Stone’s In an Iridescent Time (1959), Lucille Clifton’s Good Times (1969) and Donald Hall’s Kicking the Leaves (1978). Although innovative in their forms and subject matter, they maintained a strong adherence to clarity and sense, a coherence that would continue to resonate in their work well into the first decade of this century, when making sense hasn’t always been an aesthetic priority.

Could you pick out a few of your favorite moments from these interviews?

I was often surprised by the remarks they made, many in an off-hand manner that reflected a lifetime of honing their expression. Take, for example, Donald Hall’s insight on the nature of human emotions: “No emotion is pure, but frequently we are aware of one and not the other. In poetry somehow you come out with both.” Or Galway Kinnell’s perspective on the value of art in relation to life: “A poet should not call himself a poet. Being a poet is so marvelous an accomplishment that it would be boasting to say it of oneself.” But also “Art is wonderful, but the moment love is smashed, darkness falls, deafness falls, nothing survives as it was.”

I also like the way Jack Gilbert crystallized the difference between hubris and pride: “Real pride gives up; false pride keeps performing.” And Robert Bly’s redemptive belief in survival: “Each of us deserves to be forgiven. If only for ‘our persistence in keeping our small boat afloat when so many have gone down in this world.’”

Ruth Stone produced this startling admission: “Something funny, I can tell you, that when I’m writing I’m not experiencing anything.” Maxine Kumin confessed to a recognition that her early poems of witness, especially those in House, Bridge, Fountain, Gate, were more audacious than she realized: “I was not aware of it. Looking back they seem much more daring.” And Lucille Clifton communicated a surprising observation about her own writing rules: “I do carpentry that is needed for what’s going on, in the carpenter’s rule, not the poet’s rule. One hopes to come ever closer to what poetry wants, what that poem wants.”

What other stories or observations did they share with you that shed light on both their lives and their poetry?

In response to my question about whether she was a feminist, Ruth Stone replied, “I don’t think I’m what you’d call a real feminist . . . I discovered that among these feminists that I thought were so great they were not and they were unpleasant and selfish and icky just like everybody else . . . I had a brother I loved and I was not anti-male in any way. I loved men, you know.” Talking about her schooling, Ruth confessed, “I hardly went to school at all . . . My parents didn’t have any money to send me to school. We were poor. So, I didn’t. I just read, read, and then when I had to get a job, they just filled in I had a degree and so forth for me. I didn’t have anything at all. I have nothing.”

In regard to my question about her twelve fingers, which in African lore often signified preternatural strength and vision, Lucille Clifton responded, “Somebody told me I have hands that look like I never worked. And I’ve had a job since I was twelve. Somebody asked me . . . what it’s a metaphor for. And I said it’s not a metaphor for anything. I don’t do metaphor.”

Galway Kinnell, confessed to incurable wanderlust: “I just wanted as an earthling, to know as much as I could of the earth. When I walked for days and days at a time through some of the great Western forests, I didn’t always know where I was exactly. Some people might say I was lost. But I wasn’t. I was an earthling. This is my home. I watched the positions of the sun. I read the stars. I studied the terrain. And I had a map and compass in my pocket.”

Robert Bly, who founded the men’s movement in the seventies, became deeply involved in Jungian psychology and Sufi mysticism. I asked him how important believing in God was for the purpose of completing the masculine journey. He responded, “Well, I don’t think anyone can complete the ultimate masculine journey anyway. But you know, believing in God, I don’t know exactly what that means . . . . everyone when they’re young recognizes God in the world; it’s as natural as the sunlight in the trees or something like that. And so you have to go through a lot of labor to get rid of that.”

Jack Gilbert, who has lived as a peripatetic poet his whole life, writing and teaching around the country and Europe, surprised me by saying that he felt poetry was about seventh on his list “of things [he] wanted.” When I asked him what was more important to him than poetry, he replied, “Love, access to my life, access to people. I love being myself, to experience what there was in my life. The thing that always frightened me was to miss the important things, not from the eyes of the world, but from my eyes, my heart, my experience . . . Sometimes I think I write poetry for vanity.”

When I asked Maxine Kumin about the importance of anger in her poems she said, “Even in the poem I was just referring to [‘Jack’] in which the vet says, ‘We’ll give her one more season on grass/ and then we’ll put her down. Find a good place to dig the hole.’ And my rejection of that because she looks terrific—my supposedly dying horse. I’m not putting her down . . . I’m defying death for her, and I’m actually defying death for myself. You can’t live to this age without thinking about it, and how you’re going to leave. ”

Donald Hall lived with his wife Jane Kenyon, whose presence I still felt in his house fifteen years after she died. In talking about what it was like to share both his domestic and writing space with his wife and former student, Hall said, “About twice a year I’d knock on her door. Sometimes we met in the kitchen to have a cup of coffee, just slap ass and not even speak. Then we did speak, but people didn’t come to our house for dinner parties, we didn’t have them. Occasionally we’d have visitors from Ann Arbor or New York, but largely it was a solitude and silence that was so rich! I still have the solitude, but it’s not double . . . Of course one’s energy diminishes with age. I work an hour a day on poems. When Jane died, I tried going back to children’s books, but I haven’t been able to . . . I have no conviction that God exists or that there is an afterlife, yet I still go to this church. I love the community of it and the old people. I was still skeptical with Jane, but I was further toward belief at that time, and was a devoted churchgoer.”

There are so many memorable moments. I presumed that in their eighties and nineties all these poets would feel a sense of clarity and wisdom about their lives and careers, but this wasn’t always the case. As Galway so poignantly observes in his poem “Pure Balance”: “Clarity / turns out to be / an invisible form of sadness.” I felt privileged indeed to hear their eloquent adumbrations on their “invisible forms.”

Published on June 3, 2013