Lincoln

by Christina Thompson

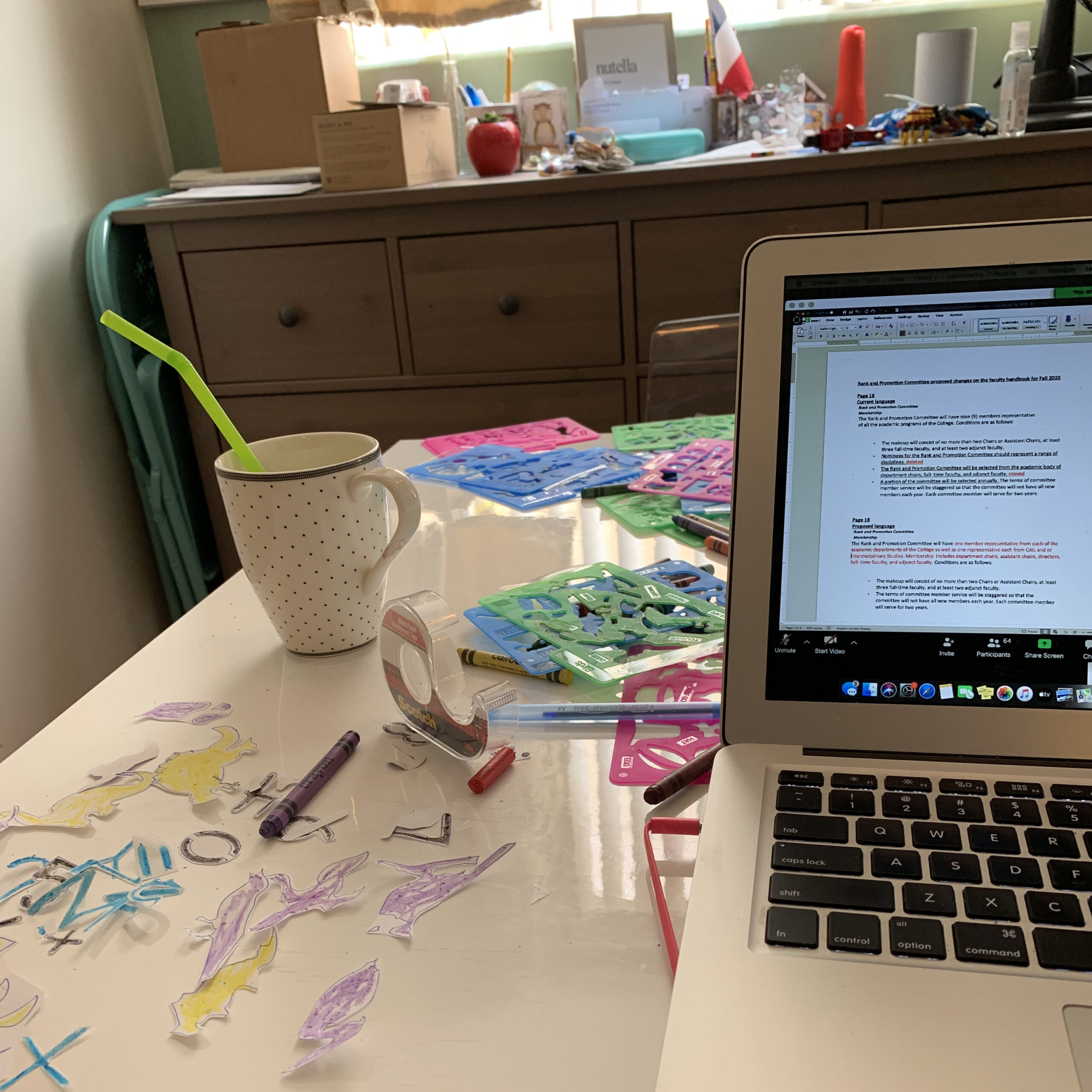

A week ago—was that three weeks into our confinement?—I sat down in my makeshift office and logged onto Zoom to teach my writing class. The screen filled with an image of my face, composed as for instruction. I waited, but no one else appeared, no ding! ding! ding! signaling the arrival of my students, logging on from their homes in the Philippines, El Paso, Duxbury, Tennessee. I was alone, just me staring back at me. Hmmm. Could they all be late? And then, eyes flicking to the corner of my screen, I had it. Tues 5:34 p.m. Wrong day.

What day is it? The question plagues me. The month is not so hard, the unmissable forsythia—that vulgar splash of yellow at the bottom of the yard—is in bloom and that means April. The year, forever engraved upon our minds. Terrible 2020: the year you wish your book had not been published, your wedding not scheduled, your once-in-a-lifetime trip not planned, the year not to graduate from high school, from college, the year not to be counting on your portfolio to retire. I wonder about babies born in a pandemic, will it mark them in some special way, the way one imagines it must mark someone to be born on the last day of February in a leap year?

But the day of the week is really hard to pinpoint. A friend, trapped at home with a spouse who is sinking into the tarpit of dementia, has developed all kinds of tricks to deal with this problem. You keep a paper calendar on the kitchen table and make a point of looking at it. You schedule things, like phone calls, with reminders on your phone. You check the date on your computer when you open it and again on the banner of the newspapers you read. You think about what day it is, again and again, because if you don’t, you’ll lose track of it altogether.

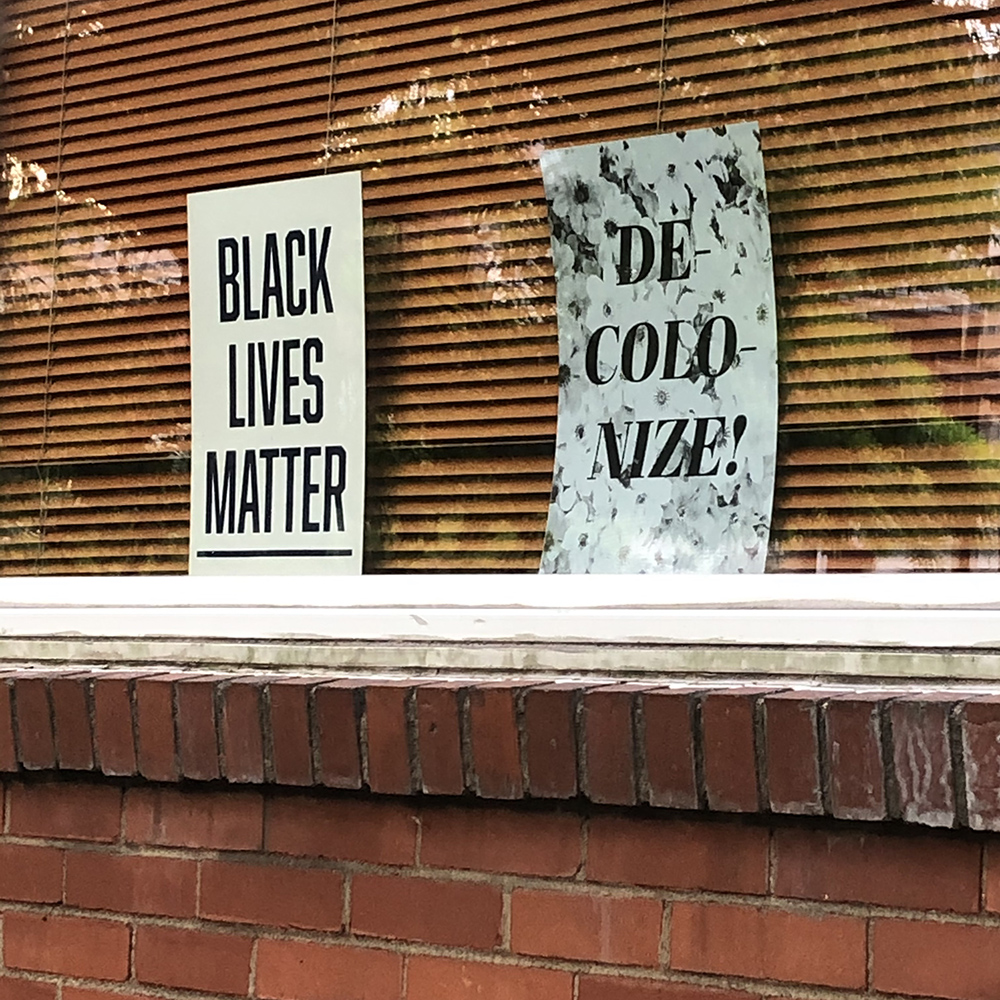

Does it even matter? I don’t know. It feels as though the tether holding me to the world of effort and ambition is slipping, as though I’m disconnecting, and not knowing what day it is feels like a sign. It should matter; it will matter again, when all of this is over and we return to some recognizable version of our lives (if, indeed, that happens). But I suppose a little slippage is not the worst thing that could be happening. I am not in the hospital, nor is anyone I love; I am not waking at 3 a.m. in a cold sweat thinking about my finances. Though, of course, all of these may yet come to pass.

I suppose what it feels most like is a kind of absentmindedness, a slackening of the line. I know I should be more taut, more purposeful: planning a new book, writing grant proposals, corresponding with people far and wide. Instead I’m drifting, like everybody else, cut loose from the ordinary anchors of our lives.

Published on April 23, 2020