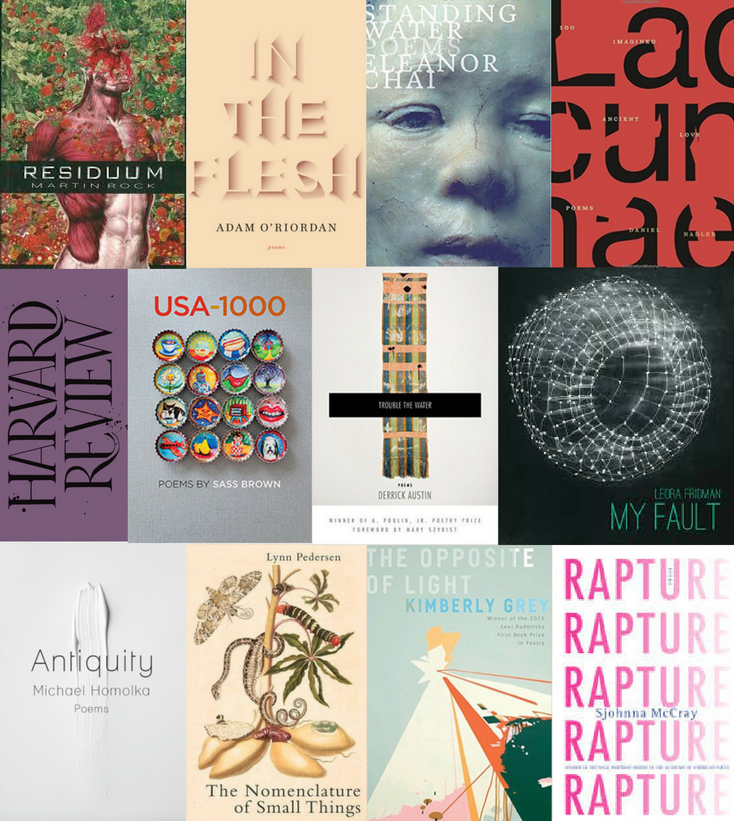

“Like Wings Unfolding in the Body”: Eleven New Poets

by William Doreski

The intelligence and accomplishment of each year’s crop of debut poetry collections always astonishes me. Poetry is one of our most widely practiced arts, but it receives too little attention in the press. Still, poets continue to offer their wares. The books considered here all deserve serious consideration and a readership beyond a few friends.

Most contemporary poetry, apart from the more aggressively experimental, is not too difficult for the average reader, though the solipsism of some post-confessional poems can be discouraging, and the frankness of others can make even the committed poetry lover uneasy. Eleanor Chai’s Standing Water [1] traces the discovery of a lost mother through an encounter with a Rodin sculpture. This unearthing makes her aware that all her life she has been possessed by lovers, by sexual predators in the Ovid mode, by her own helplessness (which she replicates through revisiting herself as an infant), and especially by her lost mother:

Most contemporary poetry, apart from the more aggressively experimental, is not too difficult for the average reader, though the solipsism of some post-confessional poems can be discouraging, and the frankness of others can make even the committed poetry lover uneasy. Eleanor Chai’s Standing Water [1] traces the discovery of a lost mother through an encounter with a Rodin sculpture. This unearthing makes her aware that all her life she has been possessed by lovers, by sexual predators in the Ovid mode, by her own helplessness (which she replicates through revisiting herself as an infant), and especially by her lost mother:

When she ended her life, she took up in mine,

a street-dwelling squatter with nowhere to go.

(“Standing Water”)

Chai sometimes relies on formal devices and rhetorical strategies made familiar by Frank Bidart’s poetry and frequently intones the cadences of middle-period Adrienne Rich, but her carefully delineated story, developed through a variety of lyric and narrative forms, is compelling. Some readers might find the air of victimhood a bit thick, but on the whole this is an effective and moving book.

Leora Fridman [2] takes a different approach to the risk of victimization. The poems in My Fault construct rhetorical defenses against the world by erecting structures that exclude threat. The opening of “Indoor Poem” exemplifies this emotional defiance:

Leora Fridman [2] takes a different approach to the risk of victimization. The poems in My Fault construct rhetorical defenses against the world by erecting structures that exclude threat. The opening of “Indoor Poem” exemplifies this emotional defiance:

I have a hyacinth

in the garden of my dreams,

where no one is drooling

over anything.

Fridman is not the most elegant poet. Her work sometimes suffers from bad rhymes, careless rhythms, and awkward modifiers. But it is bracing work, a charm against the evils of the world. Fridman armors herself with a brisk, no-nonsense stance and cuts to the gist of emotional issues so they can’t sneak up behind her. She offers a muscular stance against self-pity. Her deeply ironic title belies her strength.

Not all poets focus on their personal lives. Lynn Pedersen’s [3] most interesting poems explore the interface between science and language. The objectivity of scientific usage fascinates her. But Pedersen raises serious questions about the efficacy of science and its relation to human needs. In a fine poem about Isaac Newton, she asks:

Not all poets focus on their personal lives. Lynn Pedersen’s [3] most interesting poems explore the interface between science and language. The objectivity of scientific usage fascinates her. But Pedersen raises serious questions about the efficacy of science and its relation to human needs. In a fine poem about Isaac Newton, she asks:

What good does it do to postulate

that the sun’s density is one-quarter of the earth’s

when the next village over, its mass,

its whole populace is waning? The healthy

quarantined at home with their ill. Who knew

the moon and calculus needed one another?

(“Isaac Newton Waits Out the Plague”)

These poems ripple with facts, but point to the disjunction between language and things, and its occasionally fatal outcome: “The elephant learning not to trumpet / to avoid being killed.” Sometimes these poems get too self-conscious: for instance, italicizing words to call attention to their strangeness, an unoriginal tic. But they confront persistent issues: the relation of science to language and the efficacy or failure of an often oblique response to our needs.

Inevitably, young poets, even those working in a post-confessional mode, will draw upon the world of technology and gadgetry to infuse their work with a sense of the contemporary. Will this date them, as poems about steam locomotives seem dated even for those of us who admire steam locomotives? The dominance of technology in our world places great pressure on the imagination: the surrealism of the unconscious can hardly find a place in the surrealism of the digital world we inhabit. Kimberly Grey [4], in The Opposite of Light, can write with only slight irony, “Imagine an antique / computer,” among numerous images of the ways in which lovers place themselves in their world. Or, depicting a Midwestern wedding, “The bride kisses him / with an industrial fan.” This humorous, inventive, playful mode permeates her work, and it enlivens what could otherwise have been a tendentious sequence of love poems. Grey presents a range of free verse, from long unbroken lines to fragmented paragraphs of free-floating phrases. Despite their varied appearance on the page, her poems don’t sharply individuate themselves, but contribute to the whole sequence, which itself is memorable.

Inevitably, young poets, even those working in a post-confessional mode, will draw upon the world of technology and gadgetry to infuse their work with a sense of the contemporary. Will this date them, as poems about steam locomotives seem dated even for those of us who admire steam locomotives? The dominance of technology in our world places great pressure on the imagination: the surrealism of the unconscious can hardly find a place in the surrealism of the digital world we inhabit. Kimberly Grey [4], in The Opposite of Light, can write with only slight irony, “Imagine an antique / computer,” among numerous images of the ways in which lovers place themselves in their world. Or, depicting a Midwestern wedding, “The bride kisses him / with an industrial fan.” This humorous, inventive, playful mode permeates her work, and it enlivens what could otherwise have been a tendentious sequence of love poems. Grey presents a range of free verse, from long unbroken lines to fragmented paragraphs of free-floating phrases. Despite their varied appearance on the page, her poems don’t sharply individuate themselves, but contribute to the whole sequence, which itself is memorable.

Many contemporary poets are writing sequences, or at least arranging their poems in sequences. The ubiquitous and generic free-verse poem often benefits from being placed in an ordering that lends dramatic or narrative force to counter the static quality of the brief lyric. More sophisticated versions of the post-romantic lyric aesthetic shift tenses, juxtapose disparate tropes, invoke a fine excess, wield sophisticated rhetorical devices, and dramatize the mental leap from perception to perception. Yet relatively few new poets embrace these tactics. The meditative poem, as it was devised in the Romantic era and further developed by the Modernists, seems to be fading in favor of poems of simple perception and straight memory with as little mediation as possible, written in plain language direct as a prose memoir’s. This isn’t what Robert Lowell meant when he called for poetry to be as well-written as a Chekhov story.

But the tendencies of a given era do not always restrain poets; sometimes they simply push past them. Derrick Austin [5] wields a variety of figurative devices, modes of address, and rhetorical stances. His strongest imagery does not startle, but confirms our sense of the rightness of things:

But the tendencies of a given era do not always restrain poets; sometimes they simply push past them. Derrick Austin [5] wields a variety of figurative devices, modes of address, and rhetorical stances. His strongest imagery does not startle, but confirms our sense of the rightness of things:

A stag chews waist-high grass under an elm.

Its herd sleeps, each a bright, wet weed,

in a freshly rain-swept field turning in the wind,flashing dark then bright like a soldier’s skin—

(“St. Sebastian’s Executioner”)

Precise and focused, Austin’s language often seems ekphrastic, as though he had a picture in front of him as he writes. In a few of the poems, he clearly does, but it is his voice and vision, not his method, that are ekphrastic.

Sass Brown [6], in contrast, employs startling and challenging perceptions to jolt us out of readerly ease. Her work succeeds in disrupting ordinary domestic scenes not just to estrange but to enlighten the reader:

Sass Brown [6], in contrast, employs startling and challenging perceptions to jolt us out of readerly ease. Her work succeeds in disrupting ordinary domestic scenes not just to estrange but to enlighten the reader:

I’m not as funny as the TV, not as patient

as their dog whose lip-flap they grip

and twist into grins.

(“Practicing”)

Her poems are structurally complex, shifting scenes and rhetorical stress and unfolding into a convincing wholeness. These poems would not fall into convenient sequences. They stand complete and individual for the most part, held together by Brown’s wry and vivid perception, which she describes in “Insulation” as “Always a thick film between the world / and me,” and by her verbal energy.

Martin Rock [7] is a more deliberately experimental poet. Borrowing a trick from Arnold Schwerner (The Tablets) and placing much of his work under erasure, Rock underscores the immediacy of process and undermines the idea of the poem as a finished product. This makes the book fun to read, as the choices of phraseology come and go like hypertext:

Martin Rock [7] is a more deliberately experimental poet. Borrowing a trick from Arnold Schwerner (The Tablets) and placing much of his work under erasure, Rock underscores the immediacy of process and undermines the idea of the poem as a finished product. This makes the book fun to read, as the choices of phraseology come and go like hypertext:

I lied on my application

There was never a ghost on the roof

All roofs have been transformed

by America’s mostrecent economic downgrade

wanted renegades

beautiful retrograde.

We can never be quite sure of the subject or stance of these poems (if they are separate poems—even that isn’t clear) since the erasures and shifts in diction continually redirect us while leaving the afterimage of the rejected text in our minds. This makes for an exciting read, but it also defers many of the usual pleasures of poetry, including closure, wholeness, and deep focus. Still, the challenge is interesting.

But although such experiments can be compelling, poets, confessional or not, still embrace the emotional force if not the rhetorical sophistication of the traditional lyric. Lacunae: 100 Imagined Love Poems [8], by Daniel Nadler, is a collection of very brief untitled poems that invoke the Deep Image aesthetic of Robert Bly and the later James Wright. As the publisher notes, this aesthetic confronts “moments of intelligibility” and renders them if not paraphrasable at least perceptible through focused and sometimes startling imagery. The method goes back to Pound’s brand of Imagism, and some of Nadler’s poems suggest Pound’s famous “In a Station of the Metro.” Nadler’s poems have a flavor of their own, though, and if they don’t especially sound like ancient love poems, they have a pleasing immediacy and nicely wrought texture:

But although such experiments can be compelling, poets, confessional or not, still embrace the emotional force if not the rhetorical sophistication of the traditional lyric. Lacunae: 100 Imagined Love Poems [8], by Daniel Nadler, is a collection of very brief untitled poems that invoke the Deep Image aesthetic of Robert Bly and the later James Wright. As the publisher notes, this aesthetic confronts “moments of intelligibility” and renders them if not paraphrasable at least perceptible through focused and sometimes startling imagery. The method goes back to Pound’s brand of Imagism, and some of Nadler’s poems suggest Pound’s famous “In a Station of the Metro.” Nadler’s poems have a flavor of their own, though, and if they don’t especially sound like ancient love poems, they have a pleasing immediacy and nicely wrought texture:

The season is yet unlit

by the glint of the sewing needle.

The thread is stored away, the light

is an unwoven shirt.

This imaginative flair for the oblique but telling image makes for a good read, but also makes me wonder what would happen if Nadler dilated his aesthetic into a thirty- or forty-line poem. A whole book of miniatures can be enthralling, but it can be a little frustrating, too. And when those miniatures focus entirely on moments of high sexual tension without a supporting narrative framework, the effect sometimes causes me to avert my imaginative gaze.

Sex is not the riskiest subject in this batch of books, however. Michael Homolka [9] offers a series of poems about the Holocaust that edge toward portraying victims as weak or willing participants:

Sex is not the riskiest subject in this batch of books, however. Michael Homolka [9] offers a series of poems about the Holocaust that edge toward portraying victims as weak or willing participants:

Coiled around the family’s neck

Himmler’s intestines

comfort and protect us

(“Fourth Goshen”)

Yet something much subtler than affirmation of victimhood is occurring here. This group of poems, which opens his collection Antiquity, is really about constructing a self under the pressure of historical realities. Homolka is aware that his position doesn’t exactly privilege him: “I’m an American so I prefer pig iron,” he notes, acknowledging the gaucherie of juxtaposing himself with the glories of Horace’s classical world and the horrors of the recent past. Eventually his stance becomes a joke to himself, as he notes in “The History of Art”:

There is Christ’s birth there is Christ’s death

a few sedatives in betweenEventually an architectural

annunciation beam (a bluebird flaps overhead)and voices of everyone

who slightly irritates me

Homolka’s wry intelligence and off-kilter wit permeate these poems, along with a deep, unfashionable irony, much to this reviewer’s taste. But he’s not a poet for anyone easily offended.

Adam O’Riordan [10], self-consciously a product of Manchester, England, is a poet who may err a little on the side of convention, but his competence and polish are engaging. He is that most common variety of poet, one of familial memory verging on sentiment, but he yanks his poem from the verge of bathos with clever and telling leaps of metaphor, as in a poem that opens with a conventional beach scene and jumps to “two mongrel dogs locked and hot with instinct, / became a horse the rider moves in time with” (“Cheat”). These poems of place and moment eschew timeless abstractions in favor of domestic particulars, but estrange those homey moments with crafty and unexpected juxtapositions. His poems look more conventional than, on close reading, they actually are. While they risk and sometimes tumble into poignancy, their exactitude keeps them honest. This is poetry of real feeling. O’Riordan risks pathos, but he evades it with a larger commitment to aesthetic integrity.In the world of Sjohnna McCray’s poems [11] the body is a threatened aesthetic object. That this body is black and damaged (his father has lost a leg, for instance), or at least fragile and likely to be hurt, is a source of empowerment not of weakness. A poetic of strength renders even the most at-risk body parts viable:

Adam O’Riordan [10], self-consciously a product of Manchester, England, is a poet who may err a little on the side of convention, but his competence and polish are engaging. He is that most common variety of poet, one of familial memory verging on sentiment, but he yanks his poem from the verge of bathos with clever and telling leaps of metaphor, as in a poem that opens with a conventional beach scene and jumps to “two mongrel dogs locked and hot with instinct, / became a horse the rider moves in time with” (“Cheat”). These poems of place and moment eschew timeless abstractions in favor of domestic particulars, but estrange those homey moments with crafty and unexpected juxtapositions. His poems look more conventional than, on close reading, they actually are. While they risk and sometimes tumble into poignancy, their exactitude keeps them honest. This is poetry of real feeling. O’Riordan risks pathos, but he evades it with a larger commitment to aesthetic integrity.In the world of Sjohnna McCray’s poems [11] the body is a threatened aesthetic object. That this body is black and damaged (his father has lost a leg, for instance), or at least fragile and likely to be hurt, is a source of empowerment not of weakness. A poetic of strength renders even the most at-risk body parts viable:

I saw the small heart beating

like wings unfolding in the body. Here,

with this man, ideas of flight return.

(“Next to Him”)

Like O’Riordan, McCray courts sentiment in his embrace of family crises and almost obsessive focus on his father. But he maintains a critical stance that buffers him against the bathos of nostalgia and loss. Sometimes his humor protects him from the obvious:

Like O’Riordan, McCray courts sentiment in his embrace of family crises and almost obsessive focus on his father. But he maintains a critical stance that buffers him against the bathos of nostalgia and loss. Sometimes his humor protects him from the obvious:

A heavyset nurse bends over

my father who on his belly

looks nothing like a baby.She gently swabs

his rear end clean.

(“The Nurse & the Lights”)

This plain language resists both sentiment and irony. Is it poetry? Samuel Johnson wouldn’t think so, but in our era we recognize that tragedy and comedy flourish in the most ordinary moments. We don’t expect heroic personages to populate our poems; we expect the poems to mirror and reconstruct ourselves, and McCray and the other poets reviewed here understand that. While I miss the allusiveness of the modernist project, which placed new work in a larger literary context, and while I suspect that these young poets haven’t read as widely as poets used to, they are offering work that responds to our sociocultural moment in vivid and sometimes profound ways that deserve our attention.

These eleven poets do not represent the full range of poetry being written in English in our time. Missing are the more experimental poets, influenced by Ashbery, Charles Bernstein, Jorie Graham, Anne Carson, Susan and Fanny Howe, and others. We have to look at presses like Pressed Wafer and Burning Deck to find these poets in book form. Also missing are the sentimental poets who flood online journals with heartfelt clichés that stir empathy and disgust, and the often unpunctuated narrative ramblings favored by American Poetry Review. To fully appreciate the range of poetry in America, England, Ireland, Australia, and India today one must go online and brave the mass of digital text poured forth daily, some of it as impressive as most of the work in these published collections; much of it tendentious, amateurish, or downright idiotic. But it demonstrates that wherever English is spoken and read, poetry remains a living organism. We need the news of the human condition that poetry provides, so we must keep reading our young poets (and old ones as well), more for our own sake than for theirs.

•••

Books discussed in this review:

[1] Eleanor Chai, Standing Water. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2016. ISBN 978-0-37426-948-7. $23.00, hardcover. Return to Text

[2] Leora Fridman, My Fault. Cleveland: Cleveland State University Poetry Center, 2016. ISBN 978-0-9963167-1-2. $16.00, paper. Return to Text

[3] Lynn Pedersen, The Nomenclature of Small Things. Pittsburgh: Carnegie Mellon University Press, 2016. ISBN 978-0-88748-609-8. $15.95, paper. Return to Text

[4] Kimberly Grey, The Opposite of Light. New York: Persea Books, 2016. ISBN 978-0-89255-471-3. $15.95, paper. Return to Text

[5] Derrick Austin, Trouble the Water. Rochester: Boa Editions, 2016. ISBN 978-1-942683-04-9. $16.00, paper. Return to Text

[6] Sass Brown, USA-1000. Carbondale: Southern Illinois Press, 2015. ISBN 978-0-8093-3446-9. $15.95, paper. Return to Text

[7] Martin Rock, Residuum. Cleveland: Cleveland State University Poetry Center, 2016. ISBN 978-0-9963167-2-9. $16.00, paper. Return to Text

[8] Daniel Nadler. Lacunae: 100 Imagined Ancient Love Poems. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2016. ISBN 978-037418-269-4. $23.00, hardcover. Return to Text

[9] Michael Homolka, Antiquity. Louisville: Sarabande Books, 2016. ISBN 978-1-941411-27-8. No price given, paper. Return to Text

[10] Adam O’Riordan, In the Flesh. New York: W. W. Norton, 2016. ISBN 978-0-393-34572-8. $15.95, paper. Return to Text

[11] Sjohnna McCray, Rapture. Minneapolis: Graywolf Press, 2016. ISBN 978-1-55597-737-5. $16.00, paper. Return to Text

Published on January 31, 2017