Keb’ Mo’ and the Resonator Guitar

by Garrett Hongo

While surfing the net recently (I was looking at pictures of old guitars and bluesmen), I came across a 2017 video of contemporary blues artists Taj Mahal and Keb’ Mo’ playing a song that I recognized from years past. They strum and pick guitars, passing licks and sharing choruses of the tune, alternating lead vocals, Keb’ sometimes playing harmonica. It’s a charming session, and what’s astonishing to me is the guitar that Taj is playing. While Keb’ Mo’ plucks on a traditional wooden acoustic with a big sound hole, Taj plays something else—a gleaming metal-bodied guitar seemingly without a sound hole but with what looks like screened vents on both sides of the fretboard at the top of the instrument’s body. There’s a big T-bridge on the lower body behind the palm of his strum hand and a shiny tailpiece reaching out from the bottom.

It looks to me like an original National tricone resonator guitar (or perhaps a replica of it), designed in Los Angeles in 1927 by John Dopyera, a Slovakian immigrant. He made it for Solomon Hoʻopiʻi, master of the Hawaiian steel guitar, who was all the rage with the Hollywood film crowd back then—how about that for an all-time American multicultural mashup? In the video, Taj wears a blue aloha shirt with swirl shapes that look like fish and lilies, while Keb’ has on a fancy dress shirt. They both wear caps and jeans, but Taj has on bowling sneakers and Keb’ blue suede shoes. They glance at each other with affection throughout the session on the wonderful tune.

The song is a version of “Corinna,” a traditional blues that Taj reworked and recorded back in 1968 on his album The Natch’l Blues (Columbia) and that I heard first in a live performance in 1969 during my freshman year of college. A crowd of us sat on the floor and filled the ballroom of the student union on a Thursday night when we might’ve been studying. We hooted, yelled, and applauded for Taj, then fairly new on the scene—a young, Black bluesman who’d come with his band to play a concert. He’s tall, maybe over six feet, and in those days was slim with big shoulders and biceps, looking a lot like a football player. He wore black jeans, a plaid flannel shirt, and a Levi’s jean jacket. He’d wound a red bandana around his neck and topped himself off with a big, floppy-brimmed, off-white hat with a red feather in its black band. He stood in front of his group of musicians, arranged before an idle grand piano pushed to one end of the ballroom.

“Play ʻCorinna’! Play ʻCorinna’! ʻCorinna,’ ʻCorinna’!” someone yelled.

Taj turned toward the voice at the back of the crowd, held the shouter with his gaze a moment, then glanced around at his bandmates, who looked back, ready to play. He stepped forward, making a few kids in front, still seated on the floor, scoot back a little.

“You can’t just call up the blues anytime you like,” he lectured. “You got to live the blues. You got to love the blues. You got to feel it in your blood, people. Don’t be yellin’ at me for what you’d like me to play just ’cause you think I’m a jukebox. Be respectful. Listen to what we got to offer you. We come to share our music. We come to school you in the blues. We give you our blood boiled in the blues. Don’t yell at us, please.”

He silenced the crowd with that, all of us feeling chastened and instructed. We were college kids, most of us white, and what did we know? Music for us came off records we bought and collected, maybe shared, but who among us made it our lives? It was a grace, an indulgence, or a concert that most paid for with money from their parents. If we wore patches on our clothes they were an affectation, something we picked up at Berkeley High to show we’d rejected the mainstream thing. If we played folk music, we learned it from our precious collections of Folkways, Vanguard, and Smithsonian records—not in Appalachian hills and hollers. If we played the blues, we got it mostly from records too, the albums by British players like Jeff Beck, Peter Green, and John Mayall who’d learned it from records themselves—in their case, records by African American bluesmen. Who could argue with Taj Mahal?

“ʻCorinna’!’” the same guy yelled, adding a dry laugh when he felt the silence bury him.

The concert was sponsored by the Associated Students, led by an entrepreneurial classmate who cut a deal with the Ash Grove, an old dive out on Melrose Avenue in LA that booked blues and rock acts of a certain funky kind. Our college would get them for one night, usually on a Thursday when the Ash Grove was dark. That way, the musicians, usually from Chicago or the Southeast, would get a full week’s booking while they were out West. Before I got to college, I’d heard Ike and Tina Turner and the Ikettes there. Tina owned the room, dancing up a storm with the Ikettes, her voice gritty and body gyrating, her big wig hat flailing in the air as she spun, twined, and cool-jerked on the runway and stage of the small club. I felt the walls sweat when she pumped a lot of pain and glanced at me with a side-eye as she strutted to the music. Earlier that year, needing to rise by 6:00 a.m. for my job at LA’s Department of Water and Power, I’d missed late evening gigs by Howlin’ Wolf, Gatemouth Brown, and Koko Taylor. Taj was younger than all of them, a kind of novelty in that he was urban-born, college-educated, and had gotten into the blues as a sort of revivalist, at least two generations removed from its originators in the Mississippi Delta.

“I’m-ah sing it for you,” Taj said. “Not because you call. Not because you call or anything like that. I got honey in my heart is why I do.”

He glanced then at Jesse Edwin Davis, the Native American guitarist, whose long black hair hung like a horsetail down his back, over his concho belt, and past his waist. Then Taj turned away from the audience and picked up a battered acoustic guitar. It seemed made of wood, with big f-holes and a kind of dome-shaped, metallic top on the body just under the strings. Around the rim of the dome, there were squares or diamonds of perforations arrayed in a ring. They made it look like an aluminum vegetable steamer, ass-end up, had been screwed onto his old axe. Taj, instead of standing with his guitar, plunked himself down and sat with it cross-legged on the floor, just like the rest of us, placing the bout of his instrument in the middle of the bucket his legs made. He began to pluck out that catchy three-note sequence, shaking his head back and forth so his hat shook too, the red feather swiping at the air in front of the black finish of the piano behind him.

I saw that he plucked hard on the fifth string with his thumb, using a kind of apoyando stroke, resting it briefly on the fourth string, then plucked that fourth string and repeated the sequence many times before the rest of his band—Davis on electric guitar, an electric bass, and drums—kicked in, as Taj started singing the lyrics and melody with his gruff yet tender voice. The bass and drums locked together in a reggae beat, and Davis strummed syncopated chords just off of it. With Taj playing flourishes on his curious guitar, the tune possessed a gut-thunk that slapped against the wooden ballroom floor and, simultaneously, a sweet chime that lit the air and chandelier lights above us. He sang in a Delta-style vernacular that he “got a bird what-a whistle,” then sang the phrase “got a bird” four more times in successive lines, each underscored by the same insistent beat. And that beat got accentuated in a syncopated rhythm played on the bass and rhythm guitar, which lifted the tune into a staccato shuffle. It stumbled, jerked, and then righted itself. Though that bird “would sing,” Taj declared, “without Corinna, it sure don’t mean a natural thing.” The rhyme ended the verse and completed righteously on the beat too.

I thought I’d never seen anything like his guitar before. And I had no inkling then that I’d already heard guitars just like it on my parents’ Hawaiian records back home in Gardena. I went alone to the concert and had no friends to compare notes with that night. But the next morning, I described the strange guitar and a couple of guitar-literate friends who made a few guesses. A classmate who owned a Martin 00-18 said it was “probably a Dobro,” a wooden-bodied resonator with f-holes and steel strings that was invented during the 1930s. Someone else said it was a National, the first resonator guitar ever made, but that only a few were made of wood back then—most were steel body. How many of these kinds of guitars were there? I wondered. And what’s a resonator?

Though I can’t be sure I think that on The Natch’l Blues, his recording from 1968 with “Corinna,” Taj is playing a steel-body National Triolian, a single-cone resonator guitar made by the National String Instrument Company of Los Angeles sometime after 1930 and before 1936. In the liner notes, he lists “Miss ‘National,’ Steel-bodied Guitar,” along with harmonica, as his instrument on the album. Yet there are photographs of him, taken around the same period, posing with a wood-body resonator guitar that could have been another National guitar or one built by Dobro, a company founded by Dopyera after he split with National. There were numerous iterations of this guitar design, as it turns out, Dopyera creating many versions to satisfy not only the desires of its varied players, who’d eventually span the seemingly separate genres of Hawaiian, blues, and country music, but the demands of his market- and profit-oriented business partner, George Beauchamp.

Beauchamp was a vaudevillian entertainer who came up with the idea of a resonator guitar during the late 1920s. He wanted one loud enough to be heard above the woodwinds and the raucous brass in the orchestras that backed his act. His first thought was to take a Hawaiian steel guitar, a popular instrument of the time, place it on a pedestal that would serve as an external amplifying soundboard, and attach that to a Gramophone-like horn pointed toward the audience. Beauchamp hoped it would be an instrument of sublime sound and power. He took his idea to Dopyera, whose shop was a few blocks away from where Beauchamp lived. The craftsman and violin-maker Dopyera had his doubts, knowing a bit more about acoustics than Beauchamp, yet took the commission and made the contraption anyway, its horn bigger than a tuba’s bell. As he suspected, the giant horn colored the tone of the instrument so badly it sounded like a hornet with a cold.

Dopyera, an inventor of sorts who had several patents for other instruments (he made banjos and mandolins as well), then experimented with various alternatives, coming up with the idea for a resonator to be placed inside the body of the guitar. It would capture the vibrations of the strings and amplify them acoustically without the distortions inherent to a big horn. He made drawings, experimented with various materials, tried a single resonator, and finally settled on a design that used three small, convex six-inch aluminum cones that sat inside a circular metal basket mounted in a large cutout in the top of the guitar body. The cones were hand-spun in Dopyera’s own shop, his brother Rudy working the lathe and spinning tool. The guitar’s body was of nickel-plated German silver, fashioned by Adolph Rickenbacher, a Swiss immigrant who had a shop just down the street from Dopyera’s. For a top plate, Dopyera placed a round-cornered triangle of like metal with diamond- and pyramid-shaped screen cutouts over the cones, creating a gleaming, ornately constructed instrument unlike any guitar ever before. This was a tricone resonator with a stunning art deco look to its metal body, a honking big T-bridge, and a distinctive, metallically tinged sound, bolder and louder than any other guitar of the pre-electric era.

The three inner cones not only captured the sound of the strings, but resonated with each other and the bridge, producing a penetrating but sweet and rich sound full of upper harmonics. To debut Dopyera’s instrument, Beauchamp commissioned the Hawaiian guitar virtuoso Sol Hoʻopiʻi, who was enormously popular at the time, to play it at a party for Hollywood insiders. Taj Mahal plays one almost exactly like it in the video with Keb’ Mo’. It’s a classic of its own kind of sound—full of gutsy punch from its lower strings and capable of gliding and quivering notes in its higher registers that can captivate a listener’s ear.

I think I first heard it live when I was a child younger than five in Kahuku, Hawaiʻi, a town that neighbors Lāʻie, where my maternal grandfather had his store, today about an hour’s drive from downtown Honolulu. Then, we were a more isolated plantation community made up of the descendants of Filipino, Chinese, Japanese, and Portuguese immigrants brought to work in the sugarcane fields, which were owned by descendants of white missionaries. Kānaka ʻōiwi (Native Hawaiians) avoided plantation work for the most part, but they were part of the community too, a few families with tons of relatives in neighboring Lāʻie and Hauʻula. Both towns were full of kānaka ʻōiwi whose living came from a combination of farming, gathering from the sea, and working jobs outside of King Sugar, as it’s now called by historians. On Saturday afternoons, we’d gather on one of the church lawns to hear music that the kānakas played, usually in trios and quartets—a contrabass, a ʻukelele, and two guitars. Everyone in the group usually sang, creating marvelous harmonies that I think I can still feel in my body, especially on the high notes of a chorus.

One particular day, there was a different grouping in the quartet—instead of two Spanish-style guitars, there was only one. In place of the other guitar, there was a boy, maybe middle school aged, seated on a stool with a guitar sitting sideways across his lap. When the group started up, I saw his left hand gliding up and down the guitar’s neck, holding something that he seemed to slide across the strings. The sound he made on his guitar was like that of a yodeling tenor singing a beautiful Hawaiian-language ballad. It was like a waterfall full of yellow flowers spilling across the mossy green face of the cliff in the Koʻolau Mountains.

Lele hunehune mai la i na pali

Lele hunehune mai la i na paliThe water sprays like lace down the cliffs

The water sprays like lace down the cliffs(from “ʻAkaka Falls” by Helen Parker, translation mine)

The sound was so beautiful, I think I cried for the gift of having heard it. The Hawaiian steel guitar was like a human voice, quavering with motion in its highest notes, gorgeous throbs of music. At the age of five I could have been devoted to that sound. But the moment passed, the band launching into a hapa-haole, holoholo tune based on a paniolo cowboy rhythm, the lyrics half in English, half Hawaiian, about a road trip around the island. And the audience of villagers, parents and children, applauded in recognition and appreciation. “Kani ka pila!” someone shouted. The throng joined in on the choruses, beating time with their hands that applauded and their bare feet that slapped and stomped the cool grass right on the beat.

•

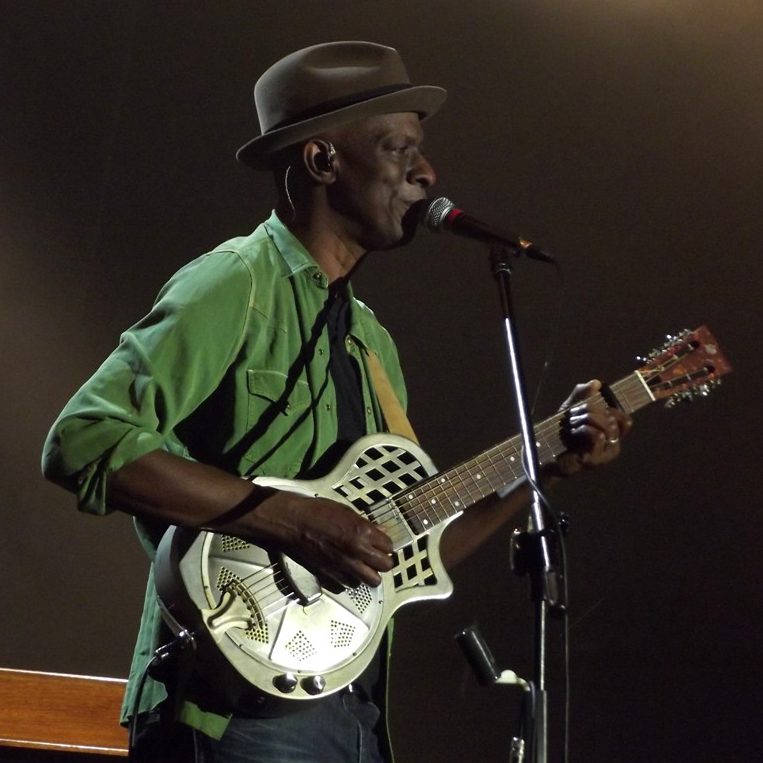

I spent an afternoon with Keb’ Mo’ recently. His given name is Kevin Roosevelt Moore; he is the winner of five Grammy Awards over a recording career that spans more than four decades, and his oeuvre extends to over eighteen records, from Rainmaker, his debut album on Chocolate City Records in 1980, to more recent works like TajMo, a wondrous collaboration with Taj Mahal released in 2017 on Concord Records. We met one early November afternoon at his home near Nashville, where I’d traveled for a literary conference. Exactly my age (we were both born in 1951), Moore grew up in Compton, California, right next door to Gardena, where I lived. If you don’t know LA, the racial shorthand was that Compton was Black, Gardena yellow. Bill Taylor, a classmate of Moore’s from high school, was a friend who’d loaned me jazz LPs throughout our freshman year. Via text, Bill introduced us, and Moore and I spoke over FaceTime for a while to get acquainted (I was in France, while Moore was in LA). He ended up inviting me for a visit once I landed in Nashville.

From my hotel near Vanderbilt University, I took a Lyft via pleasantly curving, tree-lined country roads over to Franklin, Tennessee, a swank suburb of mansions and big yards. It was the day after Halloween and there were big inflatable ghosts and witches under the sycamores on the expansive front lawns. When I got to Moore’s place, a newish three-story manse painted green and white, I entered through a side door to his basement, where the bluesman greeted me and ushered me into a big utility room, complete with a small kitchen and an area for a loveseat, an easy chair, and a corner sofa. In the middle of the room was a stand for four guitars (one of them a resonator) and another lay on the floor in an open case. On the wall over the sofa was a large poster-like painting (à la Rauschenberg) with multiple rectangular images of the singer Amy Winehouse.

Moore is a slim, lanky man over six feet tall who was dressed in blue jeans and a long-sleeved black tee, a light green ball-cap on his head. He wore high-top brown leather boots. Around his neck was a pair of breakaway reading glasses with black plastic frames. His voice is a pleasant baritone-to-tenor and he laughs frequently, his face breaking into a broad smile over a small salt-and-pepper goatee. His skin is the color of dark rum. He wears his hair cropped short and he moves easily, like a dancer, gently stretching his long frame as he bends to pick up a guitar or set it down. He tends to speak quickly, his voice so soft that I had to lean forward to catch everything when I turned the topic toward his own upbringing and beginnings in music.

“I grew up in Compton. But my mom’s from Hooks, Texas, near Texarkana, and my father’s from Heflin, Louisiana. Roots in the South. Growing up in Compton, I hung out with a couple guys who introduced me to the blues. I heard Lowell Fulsom and B. B. King records at my cousin’s place where we’d go after church, but it was old people’s music to me back then and I didn’t pay attention. So, I came to the blues late. It wasn’t until I was about fourteen, playing steel drum in a steel band that I even saw a resonator guitar. I was waiting to get into the gig at the Troubadour out on Santa Monica Boulevard, standing outside next door to the club, when I saw all these shiny guitars in the window of McCabe’s Guitar Shop. I said, ‘What kind of guitars are these with hubcaps on them?’

“A year or two later, my Vocational Drawing teacher Mr. McGee got me into a concert Taj Mahal was playing at my high school. Two periods, because the whole school couldn’t fit into our auditorium all at once. You were supposed to go only to one assembly, but Mr. McGee got me into both. He was one of those guys who knew you before you knew you. I remember hearing and seeing something very different. Taj played a National resonator guitar—all metal and bright and brisk. He played ʻShe Caught the Katy and Left Me a Mule to Ride,’ ʻPaint My Mailbox Blue,’ and of course ʻCorinna.’ I think he was playing songs that would later be on The Natch’l Blues. And it was like the universe was trying to point me there—to the blues. But it took a while.

“I was about thirty-three years old—much later, during the eighties—playing in the Whodunit Band with Charles Dennis, who later became B. B. King’s guitar player, when I got curious about the power of the blues, the fact that it had depth. I was curious about the truth in the blues. I’d been writing songs, was a working musician playing around LA, doing a few recording sessions. But I wasn’t addressing truth and authenticity.

“Around 1991, I was over at my friend Nate Larson’s house and he played two artists on the stereo. ‘Check this out,’ he said. He played Big Bill Broonzy and I thought, WTF? Then he played Robert Johnson. Then I bought the Robert Johnson box set. I borrowed an acoustic guitar. It was hard to play, man! I tried figuring out acoustic tuning. I called McCabe’s Guitar Shop and found Fran Banish, a teacher who gave me lessons. I still didn’t know that much. But I finally found myself in a search for a tone in my own voice that gave me a feeling like I had when I was a kid at my cousin’s house—that longing. I started practicing slide—finger-picking and bottle-necking. I’d heard Big Bill Broonzy and Robert Johnson, you know, and I just couldn’t go on being that shallow LA pop music boy I had been up until then.”

After a while, Moore busted out his guitar collection. He’d disappear, catlike, down the hallway and come back with guitar after guitar in their black cases, setting them on the floor, opening them up, and lifting an instrument to his side, tuning it, passing a couple along to me, inviting me to play. But I’d not touched a guitar in over forty-five years. The last time was the summer of 1972, when I gave my brother my Gibson J-50 acoustic that I couldn’t play then either.

“I got a lot of resonators,” Moore declared. “You can play anything on a resonator. It’s loud to compete with the horns. It’s boisterous, with an attitude. That’s why the Delta blues musicians took to it. Why I like it is the steel. The spider cone has a country sound. The chrome single-cone has the blues sound. I like the way it responds to the slide. It feels really down-home. The resonator gives that twangy feel like you’re down South. But I’m more of a music fan than a guy who focuses on a certain guitar. The resonator gives me a tool I need as a songwriter. I love that space between the blues and being a singer-songwriter. The resonator helps create atmosphere. It’s like I’m a carpenter and the resonator is the right saw I need to do the job. It has to do with the tones you use to get the point across. I’ve a National M-1 or M-2, a ’33 Dobro, and a National Reso Rocket—that’s my main one. I recorded Robert Johnson’s ʻCome in My Kitchen’ with it.”

We ended the gab session with Moore playing some blues. He reached first for the Regal guitar Taj Mahal had gifted to Moore after their TajMo double-bill tour together. A close replica of Dopyera’s original tricone made of German silver, the kind Sol Hoʻopiʻi first played, the Regal is metal-bodied too and of the same form factor as the Slovakian’s guitar, but is copper-tinged rather than silver-colored.

“Taj’s got all kinda sweat on it. It’s good! Funky like that,” Moore said, standing up and handing me the coppery tricone. Then he reached into another case and picked up a National M-2 mahogany resonator, its dark wooden body contrasting with the shiny metal cover plate. “I always wanted the mahogany National. I finally bought one,” he said, settling down to play it.

He commenced a sweet, finger-picking blues, the resonator cone vibrant in the air, biting a bit, thunking and emphatic as it was plucked. Moore had started a soft, lyric line with gentle, rhythmic tapping of his left foot. Then, he began sustaining the bent and flatted notes of the tune as he fell into a rhythm. It was an old spiritual, “This Is the Way I Do” sung by the Black street singer Tee-Tot, from the musical Lost Highway about Hank Williams and his tragic life. As Moore sang the lyrics, down in his baritone range, his voice grew increasingly full of character and tenderly authoritative. I could feel how he opened his throat to the long, moaning way that he sang, stretching over the vowels and bending their notes.

This is the way I do

This is the way I do in my home.

His playing was gorgeous, rhythmic, full of grace and precision, slide strumming and picking both. The single-cone resonance was a gentle thrumming against the guitar’s wooden body, escaping like a light, audible mist into the air around us. Then, Moore picked a stalking, halting lead that emphasized the downbeat and filled out the measure with deft phrases. In his hands and in his voice, the spiritual felt like a Hawaiian, slack-key “porch song” to me, a tune for casual gathering, friends getting together kani ka pila—impromptu and spontaneously, sharing spirit.

As he ended the tune, Moore executed a set of abbreviated lyric repeats and then a sweet fadeaway with his voice and guitar. The bill of his cap flipped up and down as he glanced to his instrument and then up toward me, bringing the song to a ritardando close. He laughed, and his hands, arms, and spirit all lifted lightly away from his guitar, liberated by something he’d just shared. Moore spun the instrument in his hands so it lay flat on his lap.

“This is so cool,” he said, pointing to the body, then the cover plate. “Good ’cause it’s got that wood in it and a straight cone.”

I sensed the session was over and started to take my leave. I thanked him, got up, and began saying goodbye. But Moore wanted to walk me upstairs. In the expansive parlor, we came upon his wife, ten-year-old son, and a female friend, who all greeted me amiably. It seemed they were like bandmates arranged for a record album photograph, asymmetrically dispersed around a green velvet, vaguely Victorian-looking sofa. His wife stood in front of it, the friend seated near her upon it, and his son sat sidesaddle on the far arm next to a large, floor-standing lamp with an elaborate silk shade that looked like the skirt of a large, translucent jellyfish. We exchanged light words of cheer, but it was time to go. Moore and I walked out to the porch to meet my Lyft. Before it pulled up, he said something remarkable.

“The blues originated in America,” Moore said, as we stood overlooking the gentle, S-snake of his asphalt drive. “In South Africa, when I went there, everything was joyful. You really get the depth of what was robbed from you when you feel the joy in that African music. It’s deep culture with all these animals—a tribal culture. When we were brought over, we lost all that. We got a different feeling then. It’s in the blues. And the way I connect is not necessarily from the music per se, but from the feeling I get when I hear the blues—that longing. In the body. You go back to the field hollers—that lonesome feeling of being lost. That’s the blues.”

Excerpted from Garrett Hongo’s forthcoming book The Perfect Sound: A Memoir in Stereo (Pantheon, February 2022).

Published on February 8, 2022