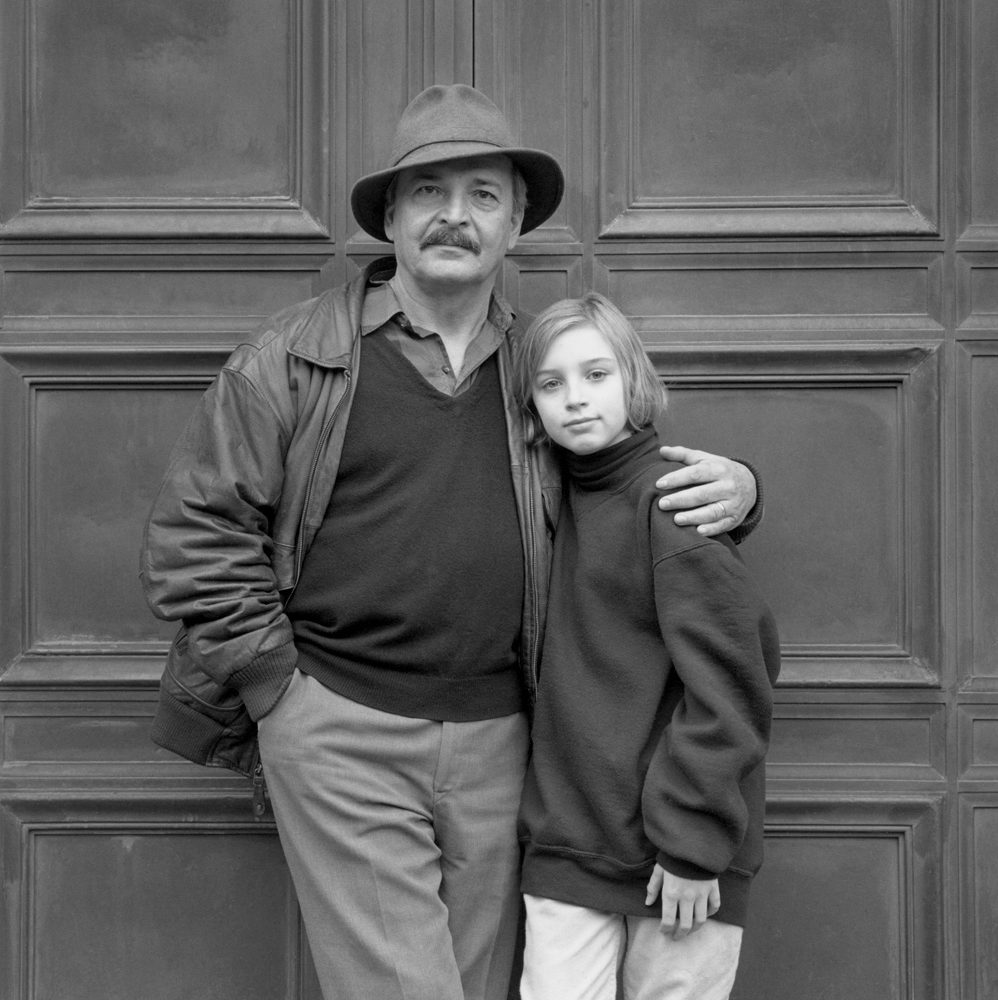

Stratis Haviaras and his daughter, 1992. Photo by Mariana Cook, from her book Fathers and Daughters (Chronicle Books, 1994). Reprinted with kind permission of the artist. © Mariana Cook, 1992.

Contributor Bio

David Rivard and Fred Marchant and Gail Mazur and Helen Fremont and Helen Vendler and Lloyd Schwartz and Michael Shinagel and Robert Scanlan and Sven Birkerts and Tatiana Averoff-Ioannou

More Online by David Rivard, Fred Marchant, Gail Mazur, Helen Fremont, Helen Vendler, Lloyd Schwartz, Michael Shinagel, Robert Scanlan, Sven Birkerts, Tatiana Averoff-Ioannou

In Memoriam: Stratis Haviaras (1935–2020)

Founding Editor of Harvard Review

We are deeply saddened to learn of the passing of Stratis Haviaras, founding editor of Harvard Review. Born in Greece in 1935, Stratis’s remarkable career brought him to Cambridge by way of Athens, New York, and Charlottesville. A writer, editor, teacher, and mentor, he was a literary citizen in every possible sense. He was the author of several collections of poetry and novels in both English and Greek, including When the Tree Sings, which was shortlisted for the Natiοnal Book Award in 1980. At Harvard, he was curator of the Woodberry Poetry Room and founding editor of Harvard Review. Upon his retirement in 2000, he returned to Greece, where he taught in the European Center for the Translation of Literature and the National Book Center of Greece and established a creative writing workshop for the Center for Hellenic Studies of Harvard University. Stratis remained a friend and contributor to Harvard Review, and we were honored to publish some of his translations online, as well as a short story in our anniversary issue, Harvard Review 50. We offer this memorial space for friends and colleagues to remember his life and work.

Stratis—I could make long sentences listing all the ways he brought his talent, dedication, and joie into our Cambridge literary life through the ’80s and ’90s. He was, lest we forget the range of his talents, novelist, curator of the Poetry Room at Harvard, founder of the long-lived writer’s group that met there on Sunday nights; founder, too, of Harvard Review, which he edited and ushered from staple-bound to perfect-bound. I knew him in all of these capacities, but right now I am picturing him in his backyard on Clinton Street, aproned, hosting—with Heather Cole—one of their fabulous summer lamb roasts, which every year pulled in writers and kindred souls from all parts of his extensive tribal network. He loved to clink the glass, make the toast, and wield the carving knife—which in his hands was a symbol of largesse.

—Sven Birkerts

For Sunday evenings and new writing read around a long table in the Poetry Room, for the founding of Erato and then Harvard Review, for the testing and weighing of poems fresh from their envelopes, for the faith you had in words and books, for the hope that there would always be new ones needed, for the translations you did, and the tape recordings you made, for the array of readings you hosted, for teaching us about a heroic age when the trees sang, and for all you gave to so many writers, including me, this deep bow of thanks.

—Fred Marchant

During my years at Harvard, Stratis was always at work improving conditions for the Poetry Room. Some of this work was invisible to readers, such as a better independence for the Poetry Room in the administrative structure of the Harvard Library System, or the resolute modernizing into digital form of the precious aural resources of the Room still in tape or LP form, which were thereby preserved for future listeners. But if those were his invisible accomplishments, he was visible daily in the Poetry Room assisting many visitors and students. He wholly believed that the room should remain available to the general public, as it continues to be. He applied for, and won, many grants for the preservation of library materials, and, since he was himself a poet, understood fully the value of such a room—open to all—in any library system. Stratis invited scores of poets—foreign as well as American—to read in the Poetry Room and arranged lectures as well, serving as host afterwards if a celebratory gathering was planned. I’m especially aware of what a good friend he was to Seamus Heaney during Seamus’s years at Harvard, and of Seamus’s affectionate regard for him. Stratis brought to the Poetry Room a wide and deep knowledge of classical and European poetry, espousing poets that many of us had not read till he sponsored a reading by them. He will be long remembered by all of us.

—Helen Vendler

I first met Stratis when he worked at Widener and came to poetry readings around Cambridge. When the Tree Sings knocked me out. To have this brilliant charismatic writer at the helm of Lamont’s Poetry Room was thrilling. Stratis was a generous friend to me (I think my second or third published poem was in Arion’s Dolphin [which he launched at Goddard College in the 1970s]) and to so many other writers, He enriched the literary community here for years in ways for which we should be forever grateful.

—Gail Mazur

Each of the journals that Stratis founded seemed to get bigger and bigger. And with time and distance, so did he. And his Cheshire Cat smile (what delicious secrets was he always preparing to spring on us?). When he moved to Greece, we missed him a lot. He was a great spirit, a welcoming editor, and a wonderful writer. We’ll miss him now more than ever.

—Lloyd Schwartz

You have to start with shit, Stratis said. He’d instructed me to buy a fifty-pound bag of cow manure, and he was now spreading it in my back yard. Writing, gardening—it’s the same for both. He was planting two pepper plants, some summer squash, zucchini, and two tomato seedlings that he’d brought over from his own garden half a mile away. As he worked, he held forth on the relationship between gardening and creativity, how plants and literature intertwine. Your writing will change now, Helen, he said. You will see interesting things start to happen in your work, once you have a garden to tend to. He did not think that living in an apartment, as I’d done for the past eight years, was good for literature, and he took it upon himself to lead me into the light of true inspiration. Well, Stratis certainly lit me up, all right. He was mentor, philosopher, friend, and co-conspirator; he delighted in bucking established norms, both in his workplace and mine. It’s ok to have a job, he assured me, but writing must always come first. Where would I be, if not for Stratis? He showed me how to love the world and to write without fear, without restraint, and it always starts with shit.

—Helen Fremont

In September of 2001, Sally and I led a small group of travelers to Turkey and Greece on a trip sponsored by Harvard Alumni Travel. It was a last-minute decision for us, as the original leader had withdrawn in the wake of the 911 attacks. I had the presence of mind to contact Stratis, who had returned to Greece, and to invite him to meet and talk to the group when we arrived at the Grand Bretagne Hotel in Athens. It went very well. Dapper in his casual way, urbane as usual, Stratis mingled easily with the dozen or so travelers having drinks amid the storied opulence of the Grand Bretagne. (It had been the headquarters of both the Nazis and the Allies in World War II.) Then he spoke. I recall that he read a couple of his poems and then talked about contemporary Greece and answered questions. It was so far above the usual canned spiel of local guides that I had a problem on my hands: expectations had been raised. The next morning at breakfast several of the group asked after Stratis. They were more than a little disappointed to learn that he would not be coming with us when we visited the Parthenon and the National Archaeological Museum before going on to the Peloponnese. Now I feel like one of those alumni travelers. Where is Stratis? Will he not join us for the rest of the journey?

—Alfie Alcorn

I was present with Stratis Haviaras at the creation of the Harvard Review with the premier issue published in the spring of 1992. I was listed as publisher along with Richard Marius and Stratis, while Stratis was the editor. After Seamus Heaney was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1995, Stratis the following year issued a Harvard Review monograph on Seamus titled “A Celebration,” which Stratis edited and to which I contributed an essay on “Seamus Heaney’s ‘Villanelle for an Anniversary.’” I was proud to serve as publisher until my retirement in 2013.

—Michael Shinagel

Stratis Haviaras occupied a rare space in American letters, and he filled it with a light that was compounded of soulfulness, shrewdness, and affection for friends and words. It isn’t simply that he opened up the Poetry Room at Harvard to the outside world, internationalizing it, but that in doing so he helped change American poetry—he’s a big part of the secret history of American poetry over the last fifty years, the true history of poets making their way in this beautiful, benighted country. The Poetry Room in those years was a clubhouse for all sorts of American poets, a place where all the factions felt welcomed.

The magazines Stratis started—Arion’s Dolphin, Errato, and Harvard Review—were essential to me as a younger writer. His nose for the real thing always seemed infallible, capacious in its appreciation of every style from the crude to the cosmopolitan. His own work, both poetry and prose, is lyrical and generous at all times, but never without a complex precision and keen estimation of the consequences that come from living how and where we do. I first heard him read from his writing at the Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown in 1984—a good five years before I actually got to know him. It was the year The Heroic Age was published, a book that blew me away when I finally sat down with it.

Stratis’s kindness and generosity are legend. On a personal level, I’ll just say that he picked me up at two very low points in my life—there was a modesty and casualness to the way he did it, no self-importance. I’m still grateful for what he did, for his friendship. His faith in my work as a writer and editor changed many things for me. It changed me. So many others I know would feel the same.

—David Rivard

My immense sense of loss upon hearing of the death of my dear friend Stratis immediately took the form of a direct address to him: “How much of this, that I am feeling now, you’ve suffered and shared. As soon as I heard, I thought of your murdered father: how that endless grief gets to stop now. Only to ache on in our memories … yours is free. Ave atque vale, best of friends.”

—Bob Scanlon

Stratis Haviaras: A Memoir by Vassilis Kounelis, translated by Tatiana Averoff

I first met Stratis Haviaras in October 2008, when I attended the novel workshop he taught at the Greek National Book Center. Stratis brought the teaching of creative writing to Greece and with it the certainty that the art of writing can be taught. He would react to critics and opponents of this view with a wink and would whisper in my ear, “They hate the young, Vassilis! They are afraid that they will steal their art and their place in the stalls!” My apprenticeship with him lasted until November 2016. During these eight years, he was my closest friend, teacher, and mentor, but also a daily interlocutor, who responded quickly to all the literary texts and ideas that passed through my mind, as I impatiently sought his opinion.

Stratis supported his teaching with warmth, generosity, endless work, and tangible results: a number of notable writers emerged from his workshops. He brought prestige and quality to the Greek National Book Center, although his removal as well as the violent closure of the Center in 2013, were very painful events for him. They filled him with disappointment that seemed to reopen deep wounds from his past.

His personal story highlights a painful period of modern Greek history. Born in 1935 to young refugees from the Asia Minor disaster, both Stratis and his younger sister Elizabeth grew up during the Nazi occupation, starving and orphaned. His thirty-five-year-old father, Christos Haviaras, a member of the EAM-National Liberation Front, was executed by the Nazis in 1944. His mother, Georgia Chatzikyriakou-Haviaras, was arrested and deported to a concentration camp in Germany, from which she returned (unlike the 109,000 Greek prisoners who left their bones there). She passed away many years later.

Stratis witnessed the bombing of his paternal home in Nea Kios, a village in Argolis, Peloponnese, and watched powerless as his neighbors removed even the stones from the fallen walls. For many months he survived on boiled cabbage and scavenged for wild greens, as he describes in his book The Telling. From the age of thirteen he worked in construction and at many other odd jobs, never forgetting his dream, finding escape in his writing. He would often recount the cruel treatment he experienced as a fifteen-year-old boy when he visited the National Library in Athens hoping to read the books he couldn’t afford to buy. The librarian blocked the entrance with his body and turned him away with the insulting phrase, “Get lost, you bum, he wants to read, my foot.” This episode, which could have been taken from the pages of Hugo’s Les Misérables, deeply hurt the young boy, but also motivated him with the power of a missile. Along with his struggle for survival, he fought equally, and perhaps even more so, for his love of literature. That is why he would advise us to work hard for a living, yet never to forget that our higher priority is to find time for the needs and the requirements of our writing.

A typical example is the episode he recounted to me in detail one summer afternoon: while working on the building construction of a well-known ship owner in Athens, he stayed overnight in the tool shed writing until the early hours. The light from the storm lamp was poor and the noise of mice dancing under the shack distracted him. In order to chase them away, he set fire to some newspapers and finally to the pages of paper he had in his hands…

Stratis began his long literary career in 1957 assisting Kimon Friar in the work of translating The Odyssey: A Modern Sequel by Nikos Kazantzakis into English, while at the same time struggling to shape his first poetic efforts on paper. During his first stay in America, he worked as a waiter and studied design. After returning to Greece in 1961, he worked as a supervising engineer in major technical projects, such as the large hydroelectric dam of Acheloos. He rebuilt with his own hands the small construction on Gravias Street in Sourmena (today’s Argyroupoli) where he housed his mother. It is an ironic twist of fate that the contract for the resale of this property was signed by Stratis and his sister in June 2015, on the very same day that capital controls were imposed in Greece!

His marriage to American engineer Gail Flynn, his immigration to America, and the birth of his daughter Electra mark major changes in his life. His early job as a clerk at Harvard’s main library paved the way for a brilliant career at the University. Less than ten years later he became Curator of the Woodberry Poetry Room and joined the teaching staff of the great American university.

In the meantime, he managed to get under the skin of the junta’s collaborators, taking a series of initiatives against the military dictatorship in Greece. A fervent believer in democracy with left-leaning ideas, he submitted a query to the US government and received an official response from the US Pentagon regarding the first use of napalm bombs in the Greek civil war. His writing and his social status made it possible for Stratis to return to Athens in 2000, no longer an outcast but with well-earned prestige. He returned to Nea Kios, his tough birthplace, where he was finally buried twenty years later.

In the summer of 2014, Stratis suggested that I present his last novel, Άχνα (Achna) (Kedros Publications, Athens), which was to be published in the fall. His proposal deeply honored me but, for reasons unforeseeable at the time, it was never implemented. Achna is an important work, and for Stratis it was much more than just another novel. It was his last grand challenge, his legacy as a creator, the swan song of a man who had fought hard to survive, to create, to be educated, and who knew how to accept and converse with death. Stratis’ relationship with death was a complex one and it runs through his work. It marked him as a boy during the Second World War: “I was almost fifteen, and the heroic age for me was over,” he writes in the closing lines of the novel.

The title of the book bears metaphorical reference to the period of the German Occupation. Literally, the Greek word achna means breath. Although rarely used now in modern Greek, one finds the word in imperative phrases such “Hold your breath, not a sound, stay hidden, don’t even breathe until the evil passes.” Metaphorically one holds one breath as a writer when one begins to realize the enormous difficulties of the task. Or, in a similar sense, as my illiterate grandmother use to say, “Think twice and think three times what you are going to say, because speech has consequences.”

This word that Stratis chose to bring out of obscurity and oblivion has the same weight and value as the words speech, poetry, drama. While the ancient Greek word achos means a sound of community, achna refers to a more personal sound; it is the echo of a person exhaling, often under duress or considerable personal pressure, such as the German occupation, the refugee issue, the migration, the memories. Achna, an inner breath lingers on the palate “and every word that comes out of him runs like saliva,” as Haviaras writes, capturing in his poetical prose his lifelong struggle with dyslexia.

“What’s up, Stratis?” I would ask him when we met at his beloved bar Filion, drinking whiskey with parmesan snack at six in the afternoon. After 2015, at the age of eighty-one, he almost always answered me without enthusiasm: “Nothing’s up Vassilis, everything is crashing down.” He had just decided to stop making his annual return trip to the United States in August. His beloved garden awaited him in vain; he could no longer toil for hours on end to rejuvenate the hardened soil after another heavy American winter.

“What are you up to, Stratis?” I can see him walking down Hippocrates street and I long to ask him again before he fades away in the distance.

“I’m collecting signatures for Hades, I’m going to meet Achna,” he answers as he walks on with a smile.

I wonder, did he finally meet her?

Vassilis Kounelis is a Greek author and lawyer. His publications include Smoked Ruins (Kastaniotis Publications, 2018) and Nomataios (Oceanida Publications, 2011).

Anyone who would like to add a comment to this page may email us at info [at] harvardreview [dot] org.

Published on March 12, 2020