In Memoriam: Adam Zagajewski

by Edward Hirsch

Adam Zagajewski was a person of great rectitude and character. He was a dear friend, someone whose friendship changed my life, and I am not yet ready to sum him up or let him go. But I am glad to speak about him because he was such a model presence for me and for so many others. There is a sorrow over losing him that started in a Krakow hospital and now radiates across the world. Adam was a somewhat contained person, but our lamentation is a violent river that overflows its banks. There is no holding it back; grief is a flood.

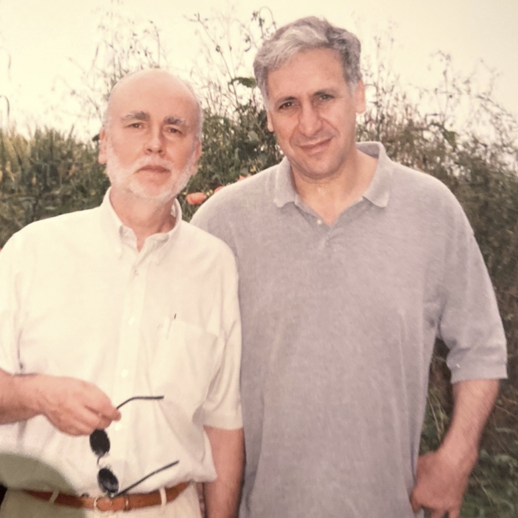

We were close allies for more than thirty years, and I do not like speaking about him in the past tense, but I suppose it is a way of coming to terms with the catastrophe. Adam was kindhearted and ever thoughtful, a reticent, somewhat introverted person, quiet by nature, modest, solitary, inclined to melancholy, though he also had a gift for friendship, a quick wit, a droll sense of humor, and a special talent for joy. I liked to try to make him laugh and see his caterpillar eyebrows arching upward. He had clear, piercing eyes. He had impeccable manners and carried himself with dignity; I consider him a sort of spiritual aristocrat, a pure artist like Thomas Mann or Rainer Maria Rilke or Zbigniew Herbert. One never doubted his implacable will—he could not be deterred from his writing life—and stirring vocation for poetry. He kept his eye on the flame.

As an intellectual, Adam had an offhanded knowledge about history that was especially impressive to Americans; we are so ahistorical as a people. There was never any doubt that he was engaged in the politics of Poland, which troubled him no end, but he also paid close attention to the vibrations of his inner life. He loved the solitude of long afternoon walks in the park. He liked to travel, mostly so that he could visit museums where he could ponder the paintings he loved, especially Dutch art from the Golden Age, but he was always eager to return home to his study in Krakow. He adored classical music—“Music reminds us what love is,” he wrote, “If you’ve forgotten what love is, go listen to music”—and spent many rapturous mornings transported by Chopin’s Ballades, Beethoven’s quartets, Schubert’s sonatas, and Mahler’s symphonies. You can tell from his poems that he was learned in the philosophers, such as Schopenhauer and Nietzsche, which appealed to his rigorous intelligence, his innate skepticism, but music affected him more viscerally, more deeply. It was an integral part of his emotional education. I was always aware that he had a vast spiritual life.

I loved Adam’s poems before I ever met or came to love him. I recall the shock and transport, the mounting excitement I felt in reading his early selected poems, Tremor, the first book of his published in English, and I resolved immediately to try to hire him in the creative writing program at the University of Houston, where I had recently begun teaching. I had no idea whether or not he spoke English or had ever taught before—it didn’t matter to me, so enamored was I of his poetry—and my passion prevailed. I argued that we had a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to try to hire an heir to Czesław Miłosz and Joseph Brodsky, a European poet of the greatest magnitude. At the time, Adam was living in Courbervoie, a suburb of Paris, and needed a job—the French did not understand the sophisticated flȃneur moving in their midst—and so in 1988 he stepped off a plane in Houston with a red scarf, a migraine headache, and a German–English dictionary. He was very polite, but he seemed tired and disoriented, and I wondered what I had done.

It was an incongruous place for him to land, but the next day we found a café and started talking about poetry, a conversation that has lasted for three decades. He seemed endlessly amused by my American openness, which wore him down and eventually cracked his carefully constructed facade. He settled in surprisingly well, partly because he discovered the Rice University Library, where the open stacks and well-stocked, mostly untouched books especially appealed to him. I was nervous that another creative writing program would poach him (many tried over the years) and did not want to tell him that quiet, open-stack libraries were a common feature of American universities. When his wife Maja came to visit, the first place that he decided to show her was the Rice Library. For the next fifteen years, Adam spent one semester a year in Houston, writing poems and teaching in our program, where he was beloved, and traveling around the country to give poetry readings. We had many adventures together—he had a sly way of disagreeing with me on panels, carving up my arguments with Old World know-how, the cutting remark (“My dear friend Eddie believes … ”)—and we sparked each other’s imaginations. His work had a tremendous impact on me personally, but it also began to impact the overall American scene.

I like to think the influence ran in two directions. After Miłosz moved back to Krakow, he missed the interchange with American poets that had been such an integral part of his life in California, and Adam got the idea of cheering him up by creating a colloquy in his honor. Together, we invented the Krakow Seminar, and for ten years we brought together Polish, European, and American luminaries (Tomas Venclova, Seamus Heaney, Eavan Boland, W. S. Merwin) to ask central questions about poetry, politics, and history. Miłosz even convinced Wisława Szymborska to read with us in a church—the church of Polish poetry. Zagajewski was one of its high priests.

I don’t think there is a better self-characterization of Adam than his poem “Self-Portrait,” which captures both how he lived day to day and what he loved abidingly. He was still residing in Paris when he wrote it in the 1990s and had not yet returned to Krakow. I had to brace myself when I first recalled it because he is so incredibly vivid in the poem—he knew himself well—and it is a bit overwhelming to reread so soon after his death. The present tense is shattering. The poem begins, “Between the computer, a pencil, and a typewriter / half my day passes. One day it will be half a century.” He speaks of living in strange cities and talking with strangers about strange topics, of listening to a lot of music (Bach, Mahler, Chopin, Shostakovich), of reading poets, dead and alive, and taking long walks on Paris streets. He likes deep sleep and fast bike rides; he goes to museums where the paintings speak to him and “irony suddenly vanishes.” He loves gazing at his wife’s face. I love the recognition at the end of the poem:

I’m truly not a child of the ocean,

as Antonio Machado wrote about himself,

but a child of air, mint and cello

and not all the ways of the high world

cross paths with the life that—so far—

belongs to me.

It is incomprehensible to me that life no longer belongs to my dear friend, whose poems put us in the presence of great mysteries. They deliver us to something profound and strange and perhaps even unlimited within ourselves. They have a strong kinship with prayer, a paradoxical longing for truth, a fiery sense of quest, and a keen longing for radiance. “God, give us a long winter / and quiet music,” he writes in his soulful poem “A Flame”: “Give us astonishment / and a flame, high, bright.”

Rereading Adam’s poems, I see that they are everywhere shadowed by death and extremely conscious of human cruelty. They recognize the recurrent savageries—the charnel house—of history, which keeps reminding us what human beings are capable of doing to each other. “It could be Bosnia today, / Poland in September ’39, France / eight months later, Germany in ’45, / Somalia, Afghanistan, Egypt,” he stated in his poem “Refugees.” “In the Parc de Saint-Cloud … I pondered your words,” he wrote to the painter Józef Czapski: “The world is cruel; rapacious / carnivorous, cruel.”

Yet Zagajewski’s poems are also filled with splendid moments of spiritual lucidity. They were spirited by what he termed “festive proclamations.” “I was impaled by sharp barbs of bliss,” he wrote in his poem “Cruel.” “I know I’m alone, but linked / firmly to you, painfully, gladly,” he noted in “Presence”: “I know only the mysteries are immortal.” For him, even the action of swimming became like prayer: “palms join and part, / join and part / almost without end.” I marvel at the way his poems transport us into a realm that is majestic, boundless, and unknown.

There are many poems of travel and transport in Zagajewski’s work, but there are three essential cities: the medieval city of Lvov, where he was born (“There was always too much of Lvov,” he confessed, “no one could / comprehend its boroughs”), the ugly industrial city of Gliwice, where he grew up (“Two cities converse with one another,” he confessed: “Two cities, different, but destined for a difficult love affair, like men and women”), and the city of Krakow, where he was a student and awakened to poetry, music, philosophy. He was a poet of Rilkean imagination, who came to believe that poetry delivers us to what is most exalted in ourselves. And yet he started out in the early 1970s on quite a different path, writing under the sign of the newborn opposition movement. He had a strong sense of the writer’s social responsibility and a clear idea that “the collectivity (the nation, society, generations) was the chief protagonist and addressee of creative, artistic works.” These early poems have a raw earthy energy, but don’t outlast their moment. Since the mid-1970s, however, he increasingly swayed to another side of his nature. He gave vent to the aesthetic and committed to the (permanent) values of art. Or as he put it: “I have discovered there is also a ‘metaphysical’ part of myself that is rather anarchic—not interested in politics or in history but in poetry and music.”

Zagajewski never forgot the importance of addressing communal concerns, the necessity of civitas, and yet he also learned the fundamental values of privacy, of the morality of speaking only for oneself. His poem “Fire” marks one turning point in his transformation from a dissident poet. It begins with the wry recognition he is probably “an ordinary middle-class / believer in individual rights.” The word “freedom” is not that complicated, he suggests, “it doesn’t mean / the freedom of any class in particular.” He recalls “the blazing appeal” of political fury, great righteousness, and the longing to burn things down:

[ … ] I used to sing

those songs and I know how great it is

to run with others; later, by myself,

with the taste of ashes in my mouth, I heard

the lie’s ironic voice and the choir screaming

and when I touched my head I could feel

the arched skull of my country, its hard edge.

The rival claims on Zagajewski’s attention yielded to deeper aesthetic, and even metaphysical, divisions. He was always a poet of compelling dualisms (“The world is torn. Love live duality! One should praise what is inevitable,” he proclaimed). A powerful dialectic operates in his work between reality and imagination, between history and philosophy, between the temporal and the eternal.

“Two contradictory elements meet in poetry: ecstasy and irony,” he asserted in Two Cities: “The ecstatic element is tied to an unconditional acceptance of the world, including what is cruel and absurd. Irony, in contrast, is the artistic representation of thought, criticism, doubt.” He weighted both elements, and yet his broadest impulse was to try to praise the mutilated world, indeed, to praise the mysteries of—and even beyond—the world itself. He was in some sense a pilgrim, a seeker, a celebrant in search of the divine, the unchanging, the absolute. His poems are filled with radiant moments of plenitude. They are spiritual emblems, hymns to the unknown, levers for transcendence. I find it bewildering and unbearable that he is gone, but I am grateful for our long friendship, and I know that his poems will companion me for the rest of my life.

Adam Zagajewski’s poetry is translated to English by Clare Cavanagh, Renata Gorczynski, Benjamin Ivry, and C. K. Williams in Without End: New and Selected Poems (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2003).

Published on November 24, 2021