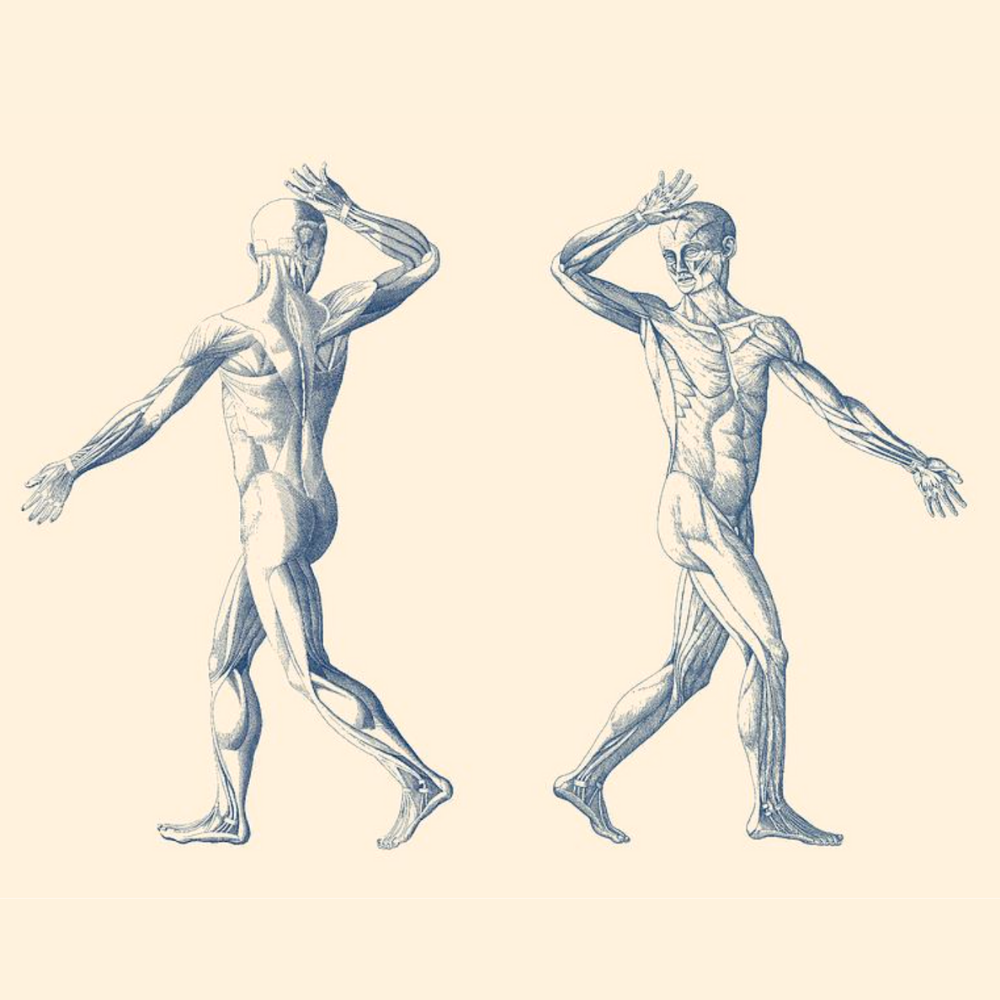

"Human Muscular System, Dual View,”

courtesy of Vintage Anatomy Prints

Contributor Bio

Reif Larsen

More Online by Reif Larsen

I Sing the Body Collective

by Reif Larsen

Each day I try to interrupt the prosaic routines of house quarantine by taking a late-afternoon walk. I follow my street in Troy, New York, down the hill to a cemetery, where I pick up a little path that runs along the banks of the Poestenkill River. The walk is a cocoon of calm, a time to be both in and of the natural world, a brief respite from fevered updates about speculative cures and apexes, away from the frenetic homeschooling of a six- and three-year-old and the handwashing and the endless worry that has subsumed our home.

The other day, as I was walking down the hill, I encountered a neighbor coming from the other direction. She was wearing a periwinkle mask and her gait was cautious. I guessed she was in her early sixties and, although I vaguely recognized her face behind her mask, I couldn’t tell you her name. As we prepared to pass, we silently co-calibrated our bodies so as to preserve a six-foot buffer between us. We were both clearly well-practiced in this ballet; by now, all of us have become experts in judging the boundaries of viral shed.

But it was not the conjuring of this compulsory cushion that stuck with me after our encounter. It was the look in her eyes, the simmering terror, the mild revulsion for my sudden presence, as if I were the enemy, as if I represented death itself.

I waved hello, startling her. Her hand curled into something resembling a reciprocal wave, and then she was gone.

•

Back in March, when everything changed, Bill McKibben wrote, “Above all, I think, a physical shock like COVID-19 is a reminder that the world is a physical place.” Physical in that the novel coronavirus, SARS-COV-2, which until very recently had never before taken up residence inside a human being, still requires contact—proximity—to transmit. Human beings thrive on proximity. Despite all of the prognostications over the last decade about our steady cultural retreat away from physical experience into the virtual compartments of our smartphones, we still crave collective closeness. We kiss, we pat, we hug, we high five, we nuzzle, we grind, we lean in, we close talk, we whisper. We lay hands upon the world to know the world.

I keep thinking back to the fateful Champions League game between Atalanta and Valencia, played at the cavernous San Siro stadium in Milan on March 10. Atalanta B.C.—a small, scrappy team from Bergamo, Lombardy—had never before made it to the Champions League and were poised, miraculously, to move on to the next round.

Their diminutive stadium back in Bergamo had been judged unfit to host club football’s most prestigious tournament, which was why 40,000 Bergamaschi traveled the forty miles south to Milan in order to witness history. Atalanta, channeling the virgin huntress after which their club was named, scored four goals that evening. Four times the home crowd leapt up in ecstasy, kissing their neighbors, fists raised in triumph, praising the heavens for their most unlikely fortune. It was a miracle: little Atalanta had slain the dragon. They were going to the quarterfinals.

The quarterfinals would never be played.

Barely three weeks later, 42,000 would test positive for the virus in Lombardy alone. Almost 7,000 would be dead. Local hospitals would be pushed past the breaking point. Doctors would face impossible decisions about which patients should be given a ventilator and which patients should be left to die. The Atalanta game is now widely cited as a “biological bomb,” one of the key mass transmission events that allowed the coronavirus to travel so widely and swiftly across the region.

I wonder: what if Atalanta had scored only twice? Or not at all? Would the numbers be the same today? The truth is that when one is dealing with exponential growth, small early interventions can have far-reaching effects. An embrace, an exhalation, a handshake can mean the difference between a life and a death—or a hundred lives and deaths, a thousand. Our brains are not equipped for such unfolding consequence. We are creatures of the here and now, not the then and there and everywhere.

•

The world is a physical place, but part of what makes this pandemic so terrifying is the invisible passage of the virus’s journey through space and time. We see its aftereffects, but we do not see it. We hear the quiet chuff of a dry cough, but we do not hear the virus enter us. The collision of virus and body unfolds on a microscopic playing field incommensurable with our own sense of self.

To counteract the virus’s prolific spread, we have been asked to be equally prolific in our stillness—everyone must stay where they are, shun the contact that nurtures and sustains us.

“When will I see my friends again?” asks Max, my three-year-old, staring out the window at an empty street.

In truth, Max seems to enjoy staying home in perpetuity. For him, memories of before have already become fuzzy. He is settling into the now, becoming adept at the niceties of videoconferencing, muting himself without being asked. When we go outside, he dons his mask with glee, a rebel pilot out to defeat the evil Empire.

But for the rest of us who still remember the before, this stillness remains a profound ask. It is not just that we have turned our bedrooms into home offices. Whole sectors of the economy have been decimated and may never come back. Wide-scale poverty will most likely become rampant. The consequences of such stillness will linger long after the virus itself is subdued.

We now have an evolving list of words for this stillness: quarantine, lockdown, mitigation, shelter in place, stay at home, self-isolate, pause. None of these terms comes close to describing our new reality, and yet still we search for a vocabulary with which to express our confusion. Like Max, we craft elaborate metaphors of war, of the enemy virus, of healthcare workers as the new soldiers, even if these metaphors continue to miss the mark. This is a crisis, yes, but it is not a war.

•

I am particularly fascinated by the term “social distancing”—by its contradiction, its inexactitude, its melancholy. The phrase cannot contain itself.

Social distancing implies some kind of emotional distance, not just a physical separation, a mentality and not just a set of coordinates. You, my neighbor, my friend, my family member, are a threat and therefore I will treat you as such. Sensing this disorientation, we have tried hard to be alone together, another contradiction in terms.

In the first days of the isolation, my wife and I found ourselves reaching out to friends near and far. I lacked a language to describe the static nature of my despair; I wanted to see if everyone was equally bereft, handcuffed by their helplessness. I scrolled through Twitter for hours, glassy-eyed, until I eventually deleted the app from my phone.

As the days wore on, and we all endured multiple Zoom meetings and classroom conferences and happy hours and birthday parties, a kind of virtual weariness took hold of me. The pixelations, the stuttering, the stilted conversations, the frozen screens, the dropped connections—it felt like we were all underwater, like the contours of reality had been put though a compression filter. It was good to see people’s faces, but I was often aware that this collection of pixels was also not them. And the seeing them but not being with them, the feeling of the constant virtual without the physical, was emotionally exhausting. I was not so much comforted by them, but by my feeling of existing at the same time as them, and this, in the end, was no real comfort at all.

If this kind of livestream socializing went on indefinitely, would we eventually replace the actual laying of hands upon the world with a virtual panopticon? Would new generations become more comfortable with the stutter-step contact of a Zoom call and eventually balk at meeting IRL? It has already begun. I once dreamed of giving my children only wooden toys, of raising them without screens. I remember when we used to talk fearfully of the dangers of “screen time.” Now, there is no such thing as screen time. There is only time.

The other day I watched as my six-year-old son, Holt, encountered a friend on a walk. I was about to warn him to observe social distancing, but I did not have to say anything. Conditioning had already set in. The two of them played, masked up, mimicking one another’s actions from a safe distance. My heart fell. My son’s sense of proximity will be forever altered by this event, whether he knows it or not. I wonder what metaphors he will use in the future to describe contact, isolation, love.

“Will I get sick from the coronavirus?” Max asked me the other day.

“Probably not,” I said. “But we have to protect other people from getting sick.”

Max nodded and put on his mask, accepting such logic without question.

•

It is tenuous logic, as evidenced by the rush to reopen the country prematurely, even as thousands continue to die each day. Protect whom? Must we really protect them when I need to get back to work? Is this quarantine even really working? Wouldn’t these people just die anyway? Not surprisingly for a nation rooted in myths of individual exceptionalism, our powerful sense of self begins to drown out our muddled conception of the collective.

As Eula Biss writes in On Immunity, her meticulous meditation on motherhood and inoculation: “Immunity is a shared space.” Vaccination works not because it protects you alone; it works because it establishes a communal immunity that doesn’t allow the virus to take hold, thereby protecting those who cannot be vaccinated themselves. Public health is a matter of shielding the vulnerable body with and literally through our own bodies.

Put this way, it is easy to see why our country has botched our response to this pandemic so badly. Culturally, we do not value shared space, just as we don’t value the body collective. And matters are not helped by the paradox of the request: we must manifest our deep connection to our species via the removal of our bodies from the public space. People must be willing to suspend their own lives, often at great financial and emotional peril, for the sake of a universal future. We must pull back to lean in. Such spiritual jujitsu leaves us drained, bewildered.

I wanted to express all of this to my neighbor on the street. In that moment of passing, in the face of her involuntary suspicion, I wanted to say, “I am keeping my distance because I care deeply about your body.” Probably best to keep my mouth shut, actually.

•

These radical shifts in personal space and public contact are difficult to fully catalogue with our rational brains. For instance: what is the future of human touch? Maybe this is why my dreams have been on overdrive; the nights are now surreal palaces of Frankensteinian memories and lives never lived. When the dots don’t connect, we often leave it to our subconscious to build the bridges. Recently, I have been circling back to a turning point in my own life that I haven’t thought about in years.

I was twenty-three and living in Brooklyn at the time. One beautifully sunny day in December I decided to go ice skating in Prospect Park. Afterward, walking back to my car with my skates slung over my shoulder, I heard a sound of someone approaching me from behind. I turned my head slightly to the right, perhaps to measure their approach. This small adjustment likely saved my life.

No one witnessed what happened, including me. I never saw my attackers. But I can give you the basics: four young men accosted me from behind. Before I could fully turn to face them, one of them swung a tree log at my head. I was unlucky to have someone swing a tree log at my head in broad daylight, but from that moment forward, I was very lucky. I never lost consciousness. They demanded my wallet. I gave it to them, though I would’ve given it to them without them smashing my head in. Awash in adrenaline, bleeding profusely, I managed to make it back to the skating rink, where an ambulance was called. A park ranger tried tending to the mess that used to be my face. I could hear the fear in her voice. I remained strangely calm even though I knew that nothing would ever be the same again.

I was seriously injured, as it turned out, but despite the extent of my injuries, my luck continued. I went through fourteen hours of reconstructive surgery, performed by one of the most talented teams in the world. The video of the surgery would subsequently be used as a teaching tool for future medical students, a fact I find simultaneously unsettling and exhilarating. My contribution to the body collective.

I am still slightly boggled at the maneuvers they performed. My forehead was shattered into seventy pieces, but the doctors managed to find them all, save one, and glue them back together. My orbitals were pulverized but they shaved off part of my skull and made me new eye sockets. By the end of the operation they had inserted thirty screws into my face, which had essentially collapsed but had still managed to protect the important squishy bits, like my eyes and my brain.

It’s a goddamn miracle, my doctors told me many times, shaking their heads. In fact, the only immediate physical effect of the attack was that I lost my sense of smell, an odd echo to one of the early onset symptoms of Covid-19, and a condition which is totally unsettling due to the elusive, intimate nature of that perception. You don’t know what it is until it’s gone. But I was not complaining—I most definitely could’ve/should’ve been blind or dumb or dead. For the most part, I’ve tried to resist this kind of speculation. Our brains are not well equipped to contemplate such consequence. Instead, I focused on being grateful for what felt like a second chance at life.

Even after my physical wounds had healed, the recovery from the trauma itself persisted. Those who have been attacked can attest to this. Trauma lingers in the mind, but it also lingers in the filaments of the body in elemental ways beyond one’s control. Even if my memory of the attack was hazy at best, my body remembered exactly what had happened—where everyone stood, the angle at which the log was swung, the subtle difference between wood smashing into your skull and, say, steel (wood has a certain give to it), not a distinction one ever wants to know.

For years after, I would jump if someone came up behind me, particularly on my right side. I scared many an innocent bystander on the street with my sudden about-face, before mumbling an embarrassed apology. Afterward, my body would begin shaking uncontrollably. Long before pandemics, I could only be around people on a street if they did not come within six feet of me.

My trust in public space was shattered, but I insisted on staying in New York City, visiting the skating rink soon after. I refused to let that trust evaporate forever. Jane Jacobs, the urbanist and resident of Greenwich village who helped save the neighborhoods of New York from Robert Moses’s dystopia of highways, once wrote, “The trust of a city street is formed over time from many, many little public sidewalk contacts.”

No matter that one of them could be an attempted murder via blunt force trauma, I did not want to shun the rest of those sidewalk contacts, which made a dense city like New York so vibrant, so alive. The ebullient busker and his ridiculous electric violin, the weary bodega owner blessed with a boundless knowledge of the cosmos, the eccentric farmer with the many necklaces who sold me beets at the market, the dancer who danced for no one in the park, the caregiver who rolled the world’s oldest man out in his wheelchair each morning to breathe in the city. I refused to replace all of these people with a version of my attackers, even if my body kept insisting I do so.

Eventually, after years and years of walking down streets in both night and day, of people approaching me from the front and the rear, my body’s elemental fear of public trespass calmed. Little by little, I began allowing people back into that orbit of personal space without flinching. I learned to trust the sidewalk, to trust the collective body once more.

•

I’ve never written about my attack before. I don’t think it was because I feared that any metaphor would prove too flimsy to carry the weight of that particular collision. The processing was just occurring on a nonverbal level, and it is only now, seventeen years later, in the middle of a pandemic, that I’ve felt compelled to address it. Perhaps it is because I spent so much time working on allowing people back into the bounds of my physical orbit, and now I have been forced to remove them from that space again. But this banishment is not born out of fear as it once was; it is an act of love. This absence is our gift right now.

Like many others, I have found that taking a walk through the woods does much to temporarily ease my anxiety. I have been watching as a stubborn upstate New York winter quietly slides into spring, its metamorphosis the sum of a thousand changes I might have otherwise ignored. There are the maroon velveteen buds on the tips of each maple branch, the shimmering blue twinkle of Siberian squill among the spongy grass, the nervous blue jay calling out his return. These changes march on, as usual. I crave them. There is comfort in the cyclical nature of such rebirth.

As I take my daily walk, I let my palm drift across the forsythia blossoms. No distance is required between us. The spring peepers call optimistically from the river valley. They say: we only have time for love. I am invigorated but also weary, for this evidence of transient natural beauty just steps from my house points me back to the real crisis after this acute crisis: will this evidence of a mass behavioral shift finally give us the courage to take radical action against climate change? We have shown that we have the capacity to radically change the world for the collective body. Will we?

When I reach the river’s edge, I encounter a hiker, an older man in his seventies. He is walking without a mask. His pace is brisk. I step off the path, respectfully.

As he passes at a safe distance, he turns to me, smiling, and says, “Thank you.”

Published on May 14, 2020