The Depicted and the Undepicted Adventures of the Traveling Dolmens by Wayne Koestenbaum

Contributor Bio

Patrick Davis and Wayne Koestenbaum

More Online by Patrick Davis, Wayne Koestenbaum

“I have a crush on the world to some extent”: An Interview with Wayne Koestenbaum

by Patrick Davis

Wayne Koestenbaum is an essayist, professor, public intellectual, and poet. (His poem, “[Misread ‘master craftsman’],” was just featured in Harvard Review 59.) In an interview with Patrick Davis, he discusses his recently completed trilogy of “trance notebooks”: The Pink Trance Notebooks, Camp Marmalade, and, this February, Ultramarine. Here Koestenbaum reflects on his various obsessions—color, kink, the Northeast corridor, Gertrude Stein—and his signature “trance poetics.”

Patrick Davis: You’ve just published the third of your trance notebooks, Ultramarine, with Nightboat Books. I’m particularly interested in how you see Ultramarine fitting into the arc of the trilogy. Is there really a conclusion to a trilogy based in trance?

Wayne Koestenbaum: In all of my long projects, there’s a movement from optimism and exaltation to a certain bittersweet sobriety by the end. That’s a writing rhythm I noticed in my book The Anatomy of Harpo Marx—how giddy the first four chapters are and how somber and death-driven the later ones are. So, I’d say that Ultramarine is more somber than The Pink Trance Notebooks and Camp Marmalade, partly because the composition of Ultramarine took much, much longer. Ultramarine is culled from four years of diaries, whereas Camp Marmalade and The Pink Trance Notebooks are one year apiece. So, there’s a larger historical terrain, much more material to condense, and therefore more of the elliptical or the elusive. And, is it fair to say, Patrick, that the world has grown darker and more dismal in these past four years or so?

PD: I think so. And that’s an interesting frame to put around this. Where was the line in your trance writing between interior and exterior?

WK: I like to think that my interior is populated by the exterior and that even the characters in my dreams come from the outside world—that my dream life reflects an attempt to rearrange the external world. That’s perhaps granting poetry power to make things happen, which is not poetry’s true provenance. But I would say that the aim of a trance poetics is certainly not solipsism or escape from the material but a re-embrace of the material through a more tactile and sonically driven relation to the corpuscles of language. That is, through a trance poetics, the closer I came to language unmediated by sense the closer I felt I was coming to reality.

PD: You said earlier that there is a more somber tone to Ultramarine, and that certainly comes from these externalities—political upheaval, deaths. Did you have a sense early on that there would be this arc across the trilogy?

WK: Not when I started, but in the revision process. I was happy to find in all three of the books that there were certain mini-narratives, like short stories or fables, buried within the flow. And I sought in revision to extend those narratives and to give them more heft and particularity. I was aware that within a seemingly random or chance-driven flow there are moments of narrative traction and obsessive return that I always attempted to flesh out and make more accessible, or to make more conventionally intense. In all three volumes, but particularly Ultramarine, I’m dancing on the lily pads of the nuances rather than explaining or delving. And there are moments when I choose a moment. Always, for me, the process of trance writing involves a certain amount of skittering and sliding, but then a sudden arrival at narrative. Narrative for me always starts to happen within the free flow of transcribing.

PD: You’re reminding me of Stein’s “loving repeating” when you mention the “obsessive return” to certain subjects or themes. Is there the same erotic impulse for language repeating as there was for Stein? Are these love poems in some way as well?

WK: There is love. I have a crush on the world to some extent. And I have a crush on what I’ve loved and what I’ve lost and on what I randomly desire, which includes a lot of, say, strangers. So, there’s a lot of cruising. And I always kept the cruising in. I kept the sex whenever there was a dirty passage, though, believe it or not, I toned it down because, well, there were limits. And I didn’t want to be typecast as a mere pervert of horndog poetics. I tried to minimize that to some extent, but I really respected, let’s say, the quality or the materiality of sexual desire, and I respected how particular, some would call it fetishistic, my sexual tastes are. Rather than smooth out my desire just into vague lust, I wanted to keep the indexes or the markers of what exactly I desire. Why is it that the bearded guy on the F train reading Walter Benjamin is the one I respected as a material arrival from the external world into my consciousness?

PD: I think that brings us back to the subject of fact, that fetish and kink are based in the intersection of fantasy and fact. We’re seeing a mainstreaming of kink now. I’m thinking of Garth Greenwell’s work, for example. Do you think there’s new territory, fresh territory, around fetish and kink seen through a properly literary lens rather than a prurient one? Are we finally examining it with the seriousness that it deserves?

WK: Yes, and perhaps with the levity it deserves too. I don’t claim to be the kinkiest guy on the block by any means. I’ve long loved the work of Dennis Cooper. He is a real model and an idol of mine, as well as a friend and supporter. His work stands out for me as an example of finely honed kink, portrayed with a certain dogged literalness. It is a rarefied species of literary craft and art. And so, I am not more kinky than Dennis or Dennis’s characters or his worldview. But I have tried to speak my desire within its authentic idiom.

PD: “Ultramarine” is defined variously as color, as touchstone, as desire, as procrastination, and as identity. In Ultramarine, you say “maybe ultramarine is again the solution, / ultramarine as base and superstructure, / return and embarkation.” Did you have a sense early on that ultramarine was kind of the oxygen flowing across this trilogy?

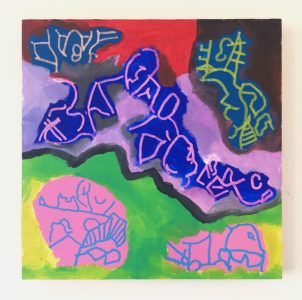

WK: I let it remain for me a bit of a mystery as I worked on the third volume to what extent ultramarine had also populated the earlier volumes. But I know, from The Pink Trance Notebooks on, that color in my life as a painter has been at the core of this book, and that therefore ultramarine has always been in my hands during the composition of all three notebooks. There’s a specific ultramarine that I often use in the base of my paintings. In fact, I can show it to you right here. [Koestenbaum presents one of his paintings to his camera.]

WK: Do you see the blue?

PD: I do.

WK: It’s not this green. It’s the blue. Underneath it is the ultramarine. So, looking at this painting, which I made in February 2014, I was already deep into using the color ultramarine.

PD: I noticed in this particular picture, there is a pink and an orange along with the ultramarine. In some ways it captures the color palette of the three books.

WK: Yes. Ultramarine is the paint that represented background, a form of night and a form of blankness on which I could write and inscribe constellations. And maybe I was also always thinking of ultraviolet too. Not only the color but maybe the Andy Warhol superstar Ultraviolet. She’s dead now, but she didn’t die that long ago. She had a studio in the building where I have a studio, maybe one or two floors below me. So, I was in the same building as Warhol’s Ultraviolet. I knew for years the third book would be ultramarine something. So I guess, yes, I did know. But I let the metaphysical or symbolic dimensions of ultramarine remain half-unconscious rather than worked out.

PD: That sense of what’s just in the background and just beneath the surface is what is so compelling about the books, because, of course, that’s what we’re all trying to access. It’s not always about our mothers or fathers. It sometimes is a layer behind or above or beyond that. Speaking of deep background, Gertrude Stein, like ultramarine, is a constant note across the books. Where was she? In the background or more in the foreground for you?

WK: Stein was originally, for me, always in the foreground, though my period of deep romance with Stein is in the past. For twenty years, I was often teaching Gertrude Stein and reading her in her entirety very passionately. I took it upon myself to be a proselytizer, a Stein defender, particularly to students who were often unwilling to get the message of Stein’s greatness. She’s a tough sell. And I really believe, I have always believed, in how accessible and joyful Stein can be and have wanted to bring that message out into the world. And though I don’t ever think that my writing is like Stein’s, the thing in my writing from Stein is a certain rhythmic propulsion. A love of simple, half-dirty or scatological words, and food, a certain materiality as well as a rhythmic, childlike propulsion. I would say that Stein arose for me particularly in Ultramarine; I think it was, in part, why I went to Paris during its composition. And there are moments where I am in Stein’s salons and city, where the music of my poems derives from that trance, the phenomenology at the core of the project. I had to think about Stein a lot, and she emerges as a hero of the book. I was aware at those moments that I was stepping forward from the background of the stage.

PD: This is the whole point of reading broadly and deeply, right? These literary moments just become part of our own language at some point. They become such a part of us that they seem to be native, when, in fact, there’s a literary genealogy that runs through us. You spoke of the tactile or physical nature of Stein’s language, the joy of the rhythm on the tongue, the propulsion. I am struck by the way you describe the trance as a physical transformation.

WK: What I’m thinking as I’m listening to you is of a very vivid image of myself on Amtrak with a window seat, looking at the Hudson or at the Long Island Sound, whether I’m going up to Boston or whether I’m going from New York to Hudson. And the rhythm of the train and the fact that the trip is two-and-a-half or three-and-a-half or four hours, and that I’m going to be writing constantly, while maybe eavesdropping and casting lascivious glances at my neighbor, offering him some nuts from my bag. There’s a swirl of a kind of random, erotic fantasy landscape, physical motion on the train, and constant writing, and maybe interludes of falling asleep. And within the writing session itself, sometimes, narratives arise. All of a sudden, from random associations, I’m suddenly on a veritable narrative track, telling a story. Certain rhythms start to arise.

For example, there’s a moment in Ultramarine that’s the June Havoc-Berlioz moment. It’s essentially a very satiny and rhythmic song with the words, the names June Havoc and Berlioz as kind of ping pong balls that are used within the rhythmic game, almost aside from their meaning. And then I think that kind of moment arrives as a joyful, physical fact in the scene of writing. It’s something to do with materiality and sensuality and sound. And those moments arise in the middle of the writing session, not in its beginning. The writing session or the transcribing session begins with self-rebuke. Boredom. Alienation. Spartan unwillingness to evolve, then loosens into song or story as it goes along.

PD: Is it fair to say that it begins from some place of writer’s block or writer’s resistance?

WK: Definitely writer’s resistance. It begins with crabbiness. It begins with an almost physical discomfort. There’s the physical discomfort of needing to sit up, sitting still and being locked into my train seat, bored, not private enough. Writing is really hard, though I love to write. The writing session and the experience of writing begins with resistance. Absolutely.

WK: You said as a reader of poetry that you like the sensuality of words. I was thinking that what I said about writing beginning with resistance and then falling into pleasure is also what happens to a reader. It’s also what a reading session is like, where when I start to read I’m resistant and I’m reading word by word, or sentence by sentence, and it’s not assembling in my mind as a flow. I’m reading too slowly in a sense, and I’m forgetting how to flow with the material. And then something else happens. I am one with the writer. I’m not taking in the words word-by-word or sentence-by-sentence, but I’m almost in a fantasy that is constructed with the writer. I’m in a feedback loop with the book, and it’s hard to tell sometimes whether I’m in the book or in my fantasy. That’s a really happy experience of reading. I have read big books just to fall into that state.

PD: Absolutely. Certainly it’s true of Proust. It’s true of Henry James. It’s true, I think, of any extended work, and certainly it was true for me reading across 1,500-plus pages of the notebooks. I was quite entranced, and it felt very intimate and very connective. It feels a bit like massaging the brain—you’re just kind of in this flow with the text, and that meaning, of course, is co-constructed. To what degree are you celebrating something informed but not academic, something massaged in a different way?

WK: I often feel, like a lot of poets and fiction writers, that we are in a state of entropic blankness. We’re in a state of funk or sadness, and there’s a sense of consciousness as an unformed, murky thing. I think why I love the novels of Jean Rhys so much: because they take place entirely in that realm of stupor. In her case often induced by alcohol but also by artfulness. My whole writing life I’ve had a sense of getting up in the morning, being at my desk and being in a sea of blankness, and gradually penetrating the work, one word at a time. And though I know that I’ve written books that are continuous intellectual journeys and that I write many sentences to give information, even in the notebooks, I’ve been tracking states of mental paralysis and emotional funk for a long time. The trance notebooks, the three volumes, have been my chance to dwell in a more generative fashion and to see that funk as a kind of opportunity for a geyser to commence.

Wayne Koestenbaum’s Ultramarine is out now from Nightboat Books.

Published on September 28, 2022