Heathrow, London

by Mona Arshi

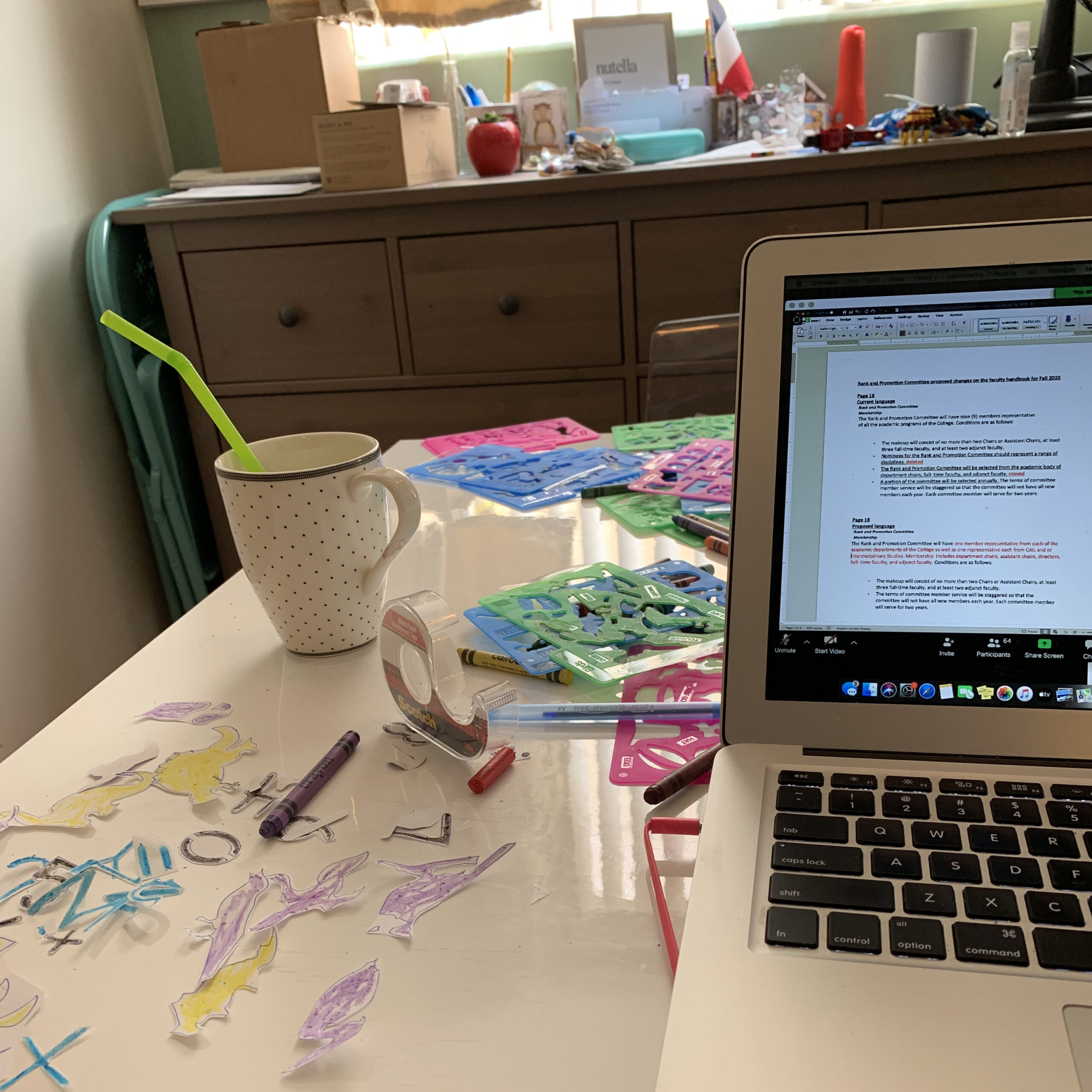

It’s true to say the present conditions make it difficult to concentrate. There’s a new white noise underneath everything, an anxiety-hum. This is no real hibernation; we have become hypervigilant animals. As a result, I can only read short and sharp-edged things: the ancients, poetry, fables. I have also paused with my children, my teenagers. Untethered from schooling in any conventional sense, they are sleeping the pandemic away. I often read them fables, the darker the better; they love the supernatural. They are shocked when I tell them that in the original version of Rapunzel, the Prince impregnated her early in the story. There’s something reassuring about the fact that our ancestors uttered these stories out loud and that they became instructions for living or outlines of some dharmic law. Not surprisingly, reality seeps into our dreaming. Our family sleep like bears; we have such clear and fantastical dreams, and when we wake, we collect them together at the breakfast table like roadkill and gently poke them. One evening I read Virginia Woolf’s short story “A Haunted House,” about a ghost couple searching for something in their old beloved home. In it, there are lines such as, “Wandering through the house, opening the windows, whispering not to wake us, the ghostly couple seek their joy.” The next morning there is a dead wasp near my pillow.

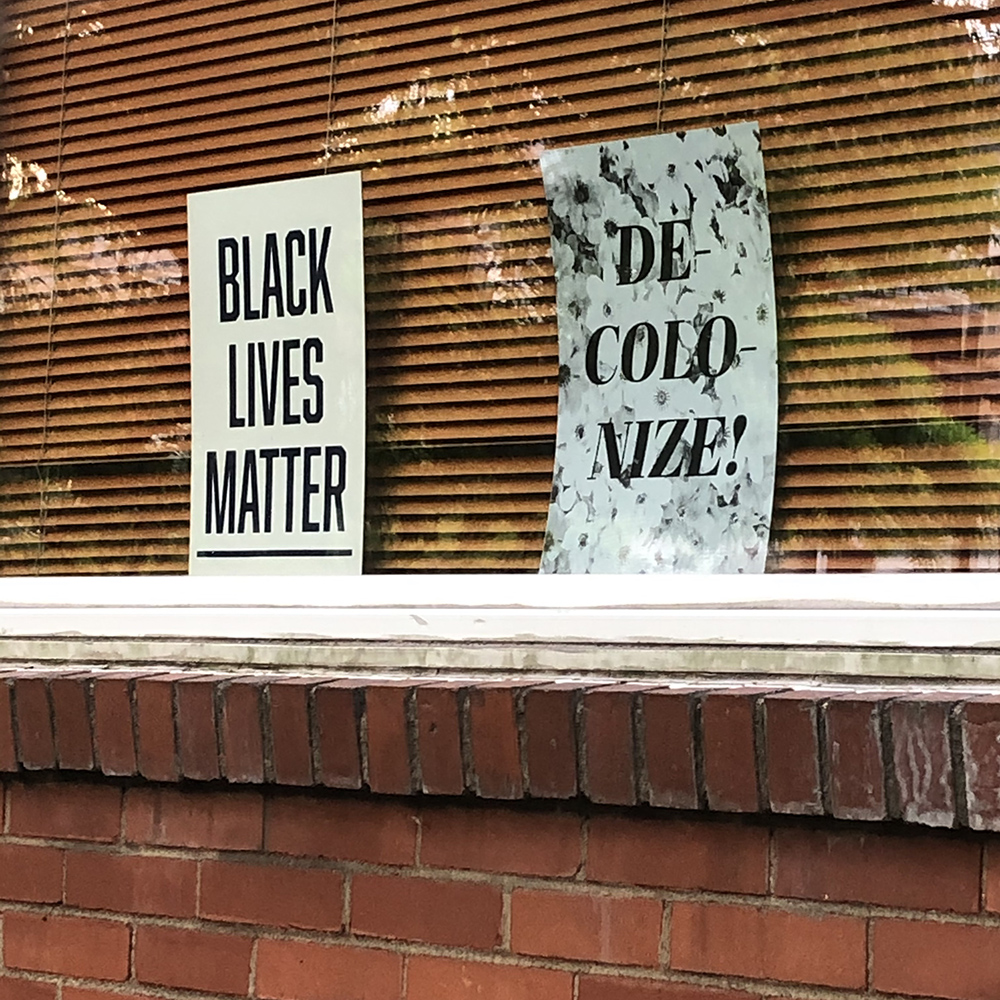

Our government leaders have deployed images of the Churchill war drive as part of our narrative; we do battle with the “enemy virus.” Parks are closed. Police powers enhanced. I go for a state-sanctioned walk each day, and it feels more and more like submission. There are days I have to remind myself I used to be a human rights lawyer. Good citizens stay at home; bad ones go shopping for nonessentials and spit on the pavement. All the while there are the numbers: 920 one day, 734 another. Friends lose fathers and grandparents, loved ones get ill, and we exchange texts. “How bad is it?” “You really don’t want to get this,” says my newly recovered friend. I can still hear the faint wheeze in her voice when she talks.

One still and warm April afternoon, I visit my mother. We meet, socially distanced, in her garden. For the first time in my life, I see and hear the green parrots puttering in the trees. My parents have always lived under the Heathrow flight path and now we manage another first: a conversation in the garden uninterrupted by planes. I look up, and there is not a single jet stream scarring the sky. Although we are reduced to essentials, I have never felt more outwardly compassionate toward the world. We discuss a photograph of Jalandhar in Punjab, where my family lives. The Himachal chain of mountains is visible for the first time in over thirty years. The image, so serenely beautiful, and the thought that my cousins might have this view now, makes me weep. I want things to return to normality, and I don’t want things to return.

Published on May 13, 2020