Contributor Bio

Ruben Quesada

More Online by Ruben Quesada

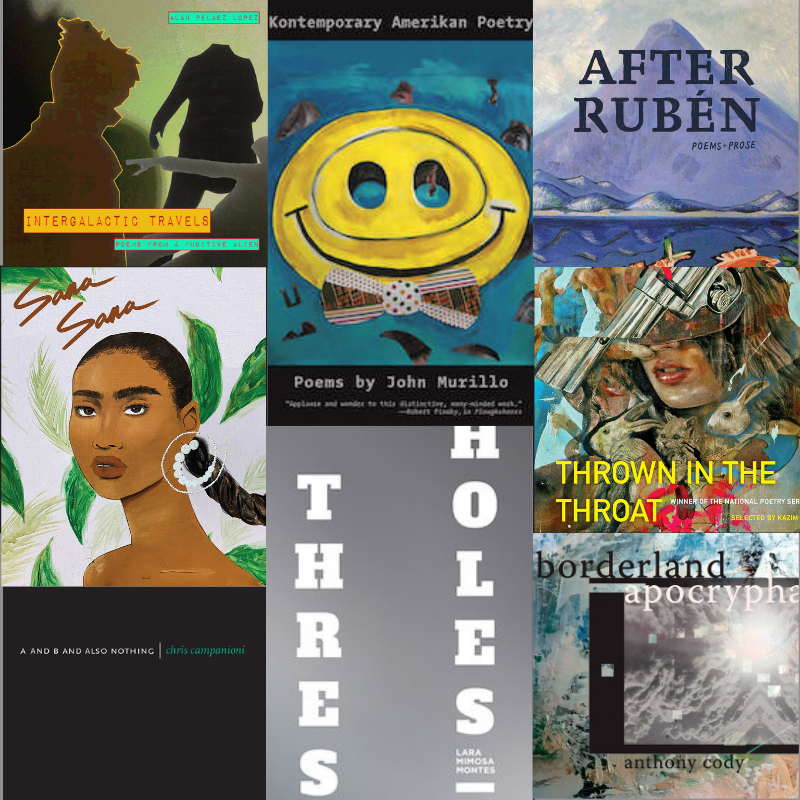

These United States: Eight Books by Latinx Poets

by Ruben Quesada

In a series of lectures, W. H. Auden claimed the job of the poet is to create secondary worlds, and that a love of the primary world leads the poet to create those secondary worlds. The writers of the following 2020 poetry collections have created a written world of experiences, not only out of love of their primary world but also, perhaps more importantly, out of the challenges they face because of their Latinx cultural and racial identities.

These eight collections are only a sample of the ever-growing number of volumes of Latinx poetry in the United States. Written by poets of varied cultural, class, and religious backgrounds, these collections transform and provoke American history and its relationship to our present moment of cultural upheaval, bringing readers one step closer to standing with the Latinx community in its many forms of expression.

•••

Game Over Books

Part prayer and part ode, Ariana Brown’s Sana Sana is a chapbook-length collection that reads as poetry and memoir. Brown’s poems dwell upon personal memories, including Spanish-language acquisition, same-sex desire, and the death of family members. This book confronts microaggressions of xenophobia, racism, and homophobia. In one of many provocative poems, “Dear White Girls in My Spanish Class,” Brown’s experience as a Black Mexican American is critical of the taxonomy of language and race often taught in US classrooms lacking cultural and colonial history:

I see you—stumbling

so hard you laugh through entire sentences

because my ancestors are a punchline [ … ]

Spanish was given to my people

at the end of a sword, forced in our throats

In the poem “Ode to Thrift Stores,” Brown writes,

A rich girl once told me

she didn’t shop in thrift stores

because they were “sad places”

and immediately I pictured

myself trotting alongside my mom

at the Community Thrift on the Southside,

the dusty heaven that produced

all my toys and dresses as a kid.

The phrase “sad places” invokes the speaker’s concerns about class and privilege, but the image of the mother and daughter “trotting” through a “heaven” in the following lines provides a moment of respite to contrast with the otherwise demeaning sentiment from the “rich girl.” Brown’s language is evocative of writers like Patricia Smith and Allen Ginsberg, who have left an indelible mark on society through their transgressive use of poetry. Brown’s poems will resonate for future audiences by encapsulating a unique relationship between race and ethnicity in our time.

•

Coffee House Press

Guided by philosophy and art, Thresholes by Lara Mimosa Montes is a poetic narrative that began as a series of blog posts about the poet’s home borough of the Bronx. The perspective travels back and forth in time and place through a series of tragic events. This volume by Mimosa Montes centers the speaker as the heroine of an epic journey. Aware of her role in a timeline of events out of her control, she writes that she “felt not the force but its pull / I move forward but not of my own accord.”

The writing is self-aware, even performative, noting that, according to Judith Butler, “to force someone to speak in a manner that does not honor improvisation, or the unconscious, is to do a violence to that person.” Mimosa Montes takes readers through events in poems that cumulatively function as documentary and confession; she claims to “live in the time of characters / rather than the time of the world.”

Months had passed. I could think of nothing but love.

○

Months had passed. I could think of nothing but loss.

○

Everything we need to live we carry inside; everything

we need is already in us to write.

Presented clearly and in a seemingly improvisational and unrestrained manner, Mimosa Montes acknowledges that her journey is simultaneously created and “undone by [her] own animal hand.” Her commitment to its forward movement results in a book-length epic about trauma and loss.

•

Red Hen Press

A post-confessional collection by Francisco Aragón, After Rubén probes personal history, political identity, and place. Imitation is the highest form of flattery, and Aragón’s collection in response to Rubén Darío’s work shows his admiration for the modernist Nicaraguan poet as well as a patchwork of contemporary poets like Ernesto Cardenal, Andrés Montoya, and Juan Felipe Herrera. He venerates the tradition of gay poets like Walt Whitman, Federico García Lorca, and Richard Blanco by imitating and rewriting their poems.

It is clear that Aragón is aware of his inheritance as a gay poet, and he uses this collection to revise queer Latin American history. In “January 21, 2013,” he embodies Darío’s voice with an imagined poetic correspondence between the now deceased Darío and the living Nicaraguan novelist Sergio Ramírez. Ramírez has denounced textual evidence of Darío’s homosexuality, and the letter to Ramírez announces,

[ … ] I’d like to think that, somehow,

you knew—and know—this truth.I’m waiting for the day when you,

the world, stop fighting it. I am

dead, and the dead are very patient.

•

Milkweed Editions

Deft and nimble, the outstanding debut Thrown in the Throat by Benjamin Garcia will both delight a reader and reinvent their understanding of the English language. Garcia confronts a world that does not often include him, considering the agility of language and showing how it can be possessed for self-empowerment. “Words have their luggage like immigrants,” says Garcia, whose words carry the experiences of coming out, having sex, questioning gender identity, and facing homophobia.

Words have their luggage like immigrants

have their customs. Huitlacoche, mariposa, maricón.

Now that I have put it in my mouth,

I am proud to be a faggot.But it sounds so hateful when you say it.

This focus on the possibilities of language returns in the poem “Nonmonogamy,” in which Garcia explores the word “know”: “And to be thoroughly fucked is to get owned. Meanings under meaning are called subtext, and words under words are called lies. I might sleep with twelve-hundred men, but who could know me more [ … ]

Garcia’s idiomatic playfulness takes us closer to understanding a lived experience—we are thrown into the throat of the speaker. It is a place of beauty and reinterpretation, as in the following lines of “The Language in Question:”

When I called you a beluga whale, I meant it

as a compliment. What a noble beast. You said this to me,

meaning me. Maybe I’m wrong, but I’m starting to think

that this comparison is not without its faults. I was wrong [ … ]

•

Otis Books | Seismicity Editions

A and B and Also Nothing is an ambitious endeavor by Chris Campanioni that asks readers to examine the ways we understand words and their meanings. What does it mean to be American or to belong to a country? Campanioni aims to “draw and draw upon, sketch out, elaborate” the meaning of citizenship and Americanization:

What does it mean to be an American. In our culture of America that would rather remove our strains of difference, rather than celebrate them, rather than recognize them and recognize difference as a prelude to power. Strength, real strength.

Language and its use or reinvention is at the heart of this collection. The book opens with and continues a discourse on the writing of Henry James and Gertrude Stein, two innovators of language. Campanioni describes language as mechanism to change our perspective on life, with the potential to create a space where “all of reality could be shifted if you only think to write it.” With self-awareness, he writes that

Every reader is a voyeur the same way every writer is an exhibitionist, flaunting their metaphysical corpus every time they put it down on paper, expecting a gaze they will never be able to meet.

In this dense collection, readers will gaze upon a mind that wrestles with the absolutes of meaning.

•

Four Way Books

John Murillo’s Kontemporary Amerikan Poetry embraces traditional forms to create a compendium of musical verses. Murillo addresses the violence against, and oppression of, Black Americans in “A Refusal to Mourn the Deaths, by Gunfire, of Three Men in Brooklyn,” a fifteen-sonnet sequence that disrupts the standard crown form by taking the first line of one sonnet and making it the last of the next. This new arrangement is more expansive; it creates a movement between the linked sonnets, a dialogue between the interior and exterior.

[ … ] You’ve heard this one before.

In which there’s blood. In which a black man snaps.

In which things burn. You buy your matches. Christ

is watching from the wall art, swathed in fire.

Murillo’s rhythms draw his reader in to consider the complex problems of race in the United States. W. B. Yeats wrote that the purpose of rhythm in any artwork “is to prolong the moment of contemplation … by hushing us with an alluring monotony.” Over the course of these sonnets, we ruminate on inescapable, institutional oppression, police violence, the media’s vilification of Black Americans, and on the desire for a revelation—of Biblical proportions—that Black Lives Matter.

With Kontemporary Amerikan Poetry, Murillo participates in the transgressive poetic tradition of taking an inherited poetic form and making it one’s own. Most recently, readers will remember Terrance Hayes’s award-winning American Sonnets for My Past and Future Assassin (2018) which took the traditional fourteen-line form but relinquished meter. Gerald Stern’s 2002 collection American Sonnets loosened the form and meter of the sonnet entirely by exceeding the fourteen-line count and omitting metrical elements. And in The Man with Night Sweats (1992), Thom Gunn used poetic form to address a crisis, that of HIV/AIDS. In Murillo’s poetry, the crisis at hand is the deaths of Black Americans.

•

The Operating System

Alan Pelaez Lopez’s Intergalactic Travels offers readers a deeply personal and dense collection of collages, documents, drawings, images, erasures, concrete poetry, and text. The volume begins with a quote from “A Legacy of Slavery,” an essay by Colin Palmer that documents the history of enslavement in what is now Mexico, dating back to the sixteenth century and continuing to affect present-day communities and people:

In the sixteenth century, New Spain—as Mexico was then called—probably had more enslaved Africans than any other colony in the Western Hemisphere. Blacks were present as slaves of the Spaniards as early as the 1520s.

This is a documentary poetics that illuminates the intersection of Indigenous, Black, and Latinx identities, giving readers a first-hand experience of contemporary concerns, from race to immigration status to familial survival:

i keep thinking of trayvon martin and nia wilson’s death. i don’t know what it is that i’m fighting for at this moment. i use to think that my biggest problem was being undocumented. it’s not. i am learning to be black in the united states and it’s hard. [ … ] we’re the black ndns who survived. and still, amá assures me that the problem isn’t blackness or ndn-ness, the problem is the settler’s world, particularly settler rage, settler fear, and settler citizenship.

This collection simultaneously functions as a manifesto and a poetic form of witness to a lived experience at the intersections of culture, race, and migration.

•

Omnidawn

Anthony Cody’s avant-garde collection Borderland Apocrypha, a finalist for the National Book Award in Poetry, collages text and visual imagery with free verse, concrete poems, erasure poems, overlapping text, and newspaper clippings. A beautifully designed book, the text is printed in landscape orientation, pushing against the boundaries of the page.

As with these other collections, Cody tells of personal history and family trauma. Setting poems amid the historical context of the lynching of Mexicans in the United States throughout the nineteenth century, he offers readers insight into a moment that has often been excluded from American history. He uses images to capture these moments in more than just words, creating an interactive space for deep engagement by deconstructing sentences and historical information. See, for example, this single page:

Borderland Apocrypha embeds poems in reproductions of obfuscated documents to reify the historical erasure of violence against Mexican Americans. Cody makes his reader face what has been forgotten and swept under the rug, pushing our understanding of history—and also, importantly, our understanding of how books might evolve—to reflect our modern, multimodal forms of communication.

•••

These Latinx poets use history to inform readers of an overlooked past, to understand the present moment, and to document complexities of culture and identity. Whether it’s Murillo’s use of form, Brown’s investigation of language, or Cody’s focus on documentary, these (and many more) poets open a window through which readers can glimpse the history and origins of these United States from the perspective of Latinx people. Purpose and intent—particularly the intent to preserve fact and fiction—is at the heart of all of these collections, which embody the Latinx experience through space and time, at the intersections of race, history, and language.

Published on December 11, 2020