Eastern North Carolina

by Meaghan Mulholland

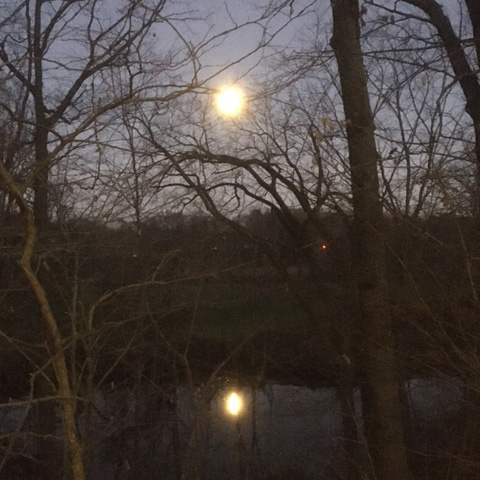

I’m driving an empty stretch of road toward the Alligator River Wildlife Refuge at dusk, hoping to spot a wolf, when a roadside sign catches my eye. It’s been raining all day, alternating in sheets and spatters against the roof of the cabin where I’m staying at Stumpy Point. Daylight is fading, but I know I’ll forget about the sign later, and I’m curious—it looks like a historical marker of some kind. I pull onto the shoulder and read:

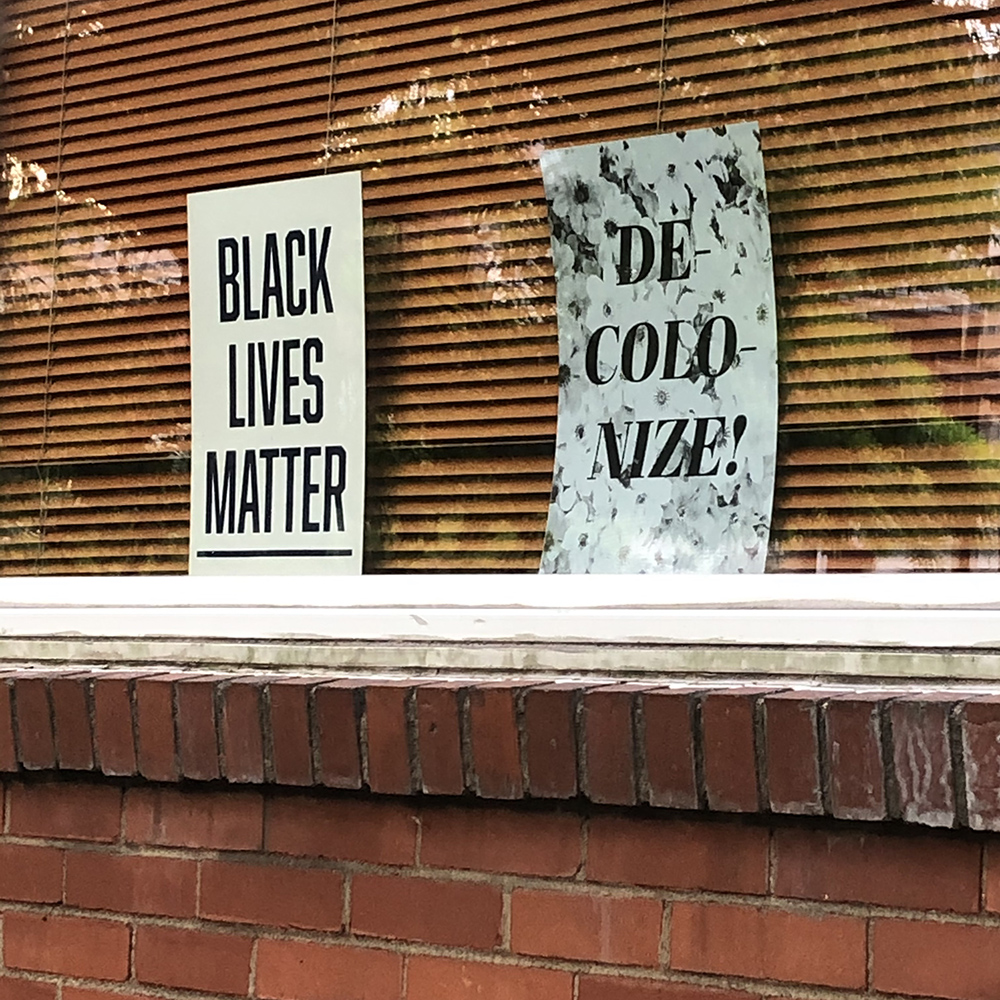

Dasemunkepeuc. Algonquian village at time of Roanoke voyages. Abandoned 1587 in this vicinity.

Through the windshield, the words blur and come into focus again with each pass of the wiper blades. Around me are acres of flat marsh and bogland, occasional clumps of shrubbery called pocosins, an Algonquian term for “swamp-on-a-hill.” The horizon is lost in mist. No trace of a village, which isn’t remarkable, given how long ago it was abandoned—but I’m surprised and a bit saddened regardless.

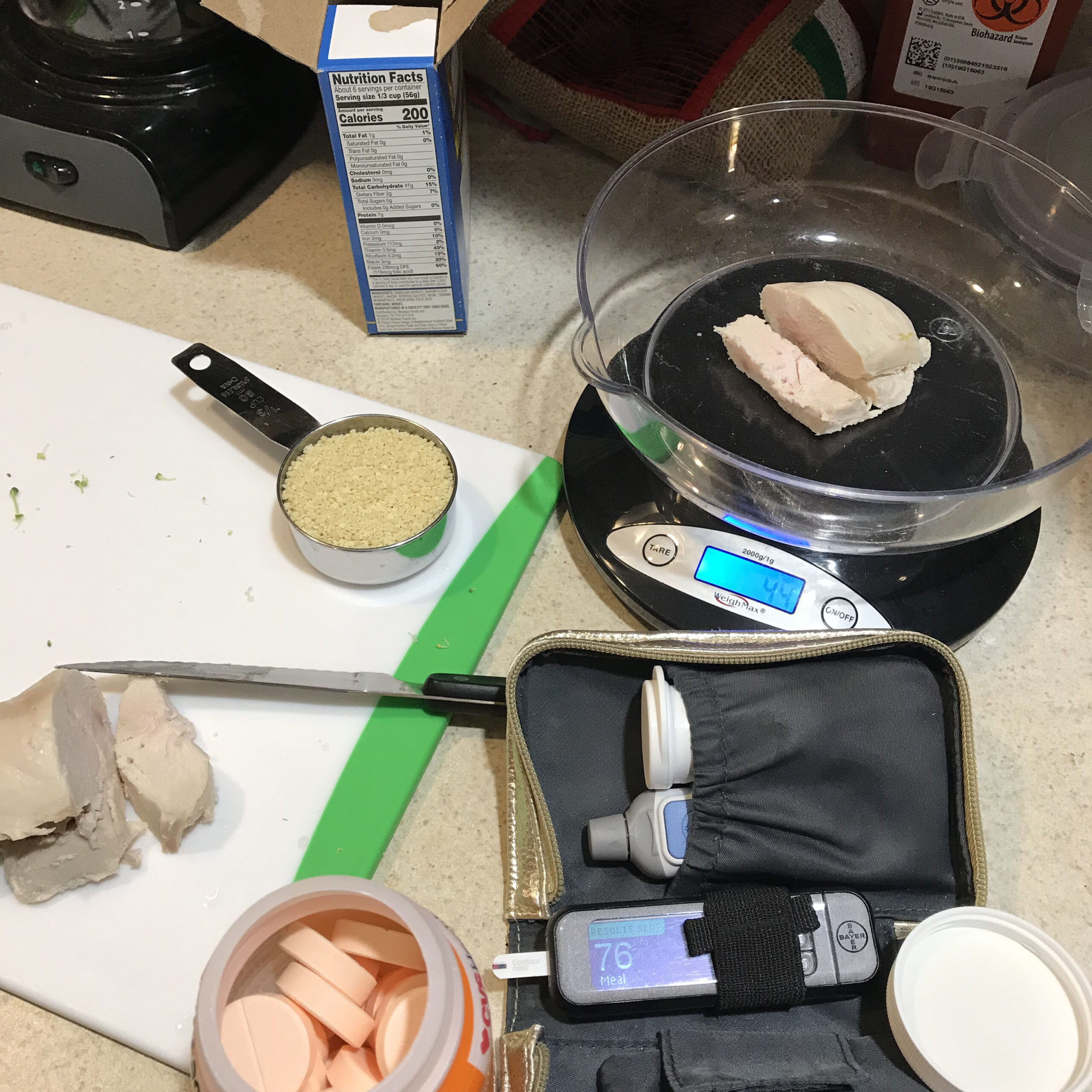

I’ve been preoccupied with disappearances lately. I’m working on a book about endangered red wolves, only ten of which are known to remain in the wild. They live nowhere else but here, on this swampy peninsula just west of the Outer Banks, which scientists predict will be underwater within a hundred years. Earlier today, I interviewed the biologist managing their recovery (seated, appropriately distanced, in our respective cars) and spent the remainder of the afternoon driving around trying to glimpse one. They are notoriously elusive, camouflaging with the landscape, but I have telemetry data from the biologist (the wolves all wear tracking collars), and know at least the general area in which they might be found.

The sun’s about to set, but I can’t resist taking out my phone and typing in Dasemunkepeuc. I learn it was likely a large village; the tribe’s leader called it home. When Europeans attacked in 1586, inhabitants were already dying of diseases colonists had brought. During the ambush, their chief was shot and fled to some woods, pursued by a colonist who later emerged carrying his severed head.

I pull back onto the road, and soon I’m cruising the puddled lanes of the refuge, navigating around deep ruts, scanning the fields for any movement. When last I was here, one year ago, I was just embarking on this project, excited about the discoveries ahead. Then the pandemic hit. I got sick in July, and I’m still sick: headaches, fatigue, hair falling out. Half a million Americans are dead. The counties surrounding this refuge are among the poorest in the state. Here hunting is a way of life, and people are necessarily more concerned with their own daily struggles than the fate of a few endangered canids. Trump campaign signs and banners are still planted in front yards, still sagging over shop windows. In the gas station market, I’m the only one wearing a mask.

Wolves in North Carolina are either symbols of unconstitutional federal intrusion or untamed beauty. In reality, of course, wolves are just wolves. The Lakota people considered them another tribe that roamed the Great Plains—the Wolf Nation. I pull onto the shoulder, turn off the engine, roll my window down and squint into the rain. Somewhere, gliding through stands of cypress, black gum or loblolly, perhaps crouching in the reeds beside a black canal, the creatures I seek are waiting for darkness. I know I won’t see them, but still I linger—the night settling over me like a blanket, the rain drumming softly on the roof.

Published on March 15, 2021