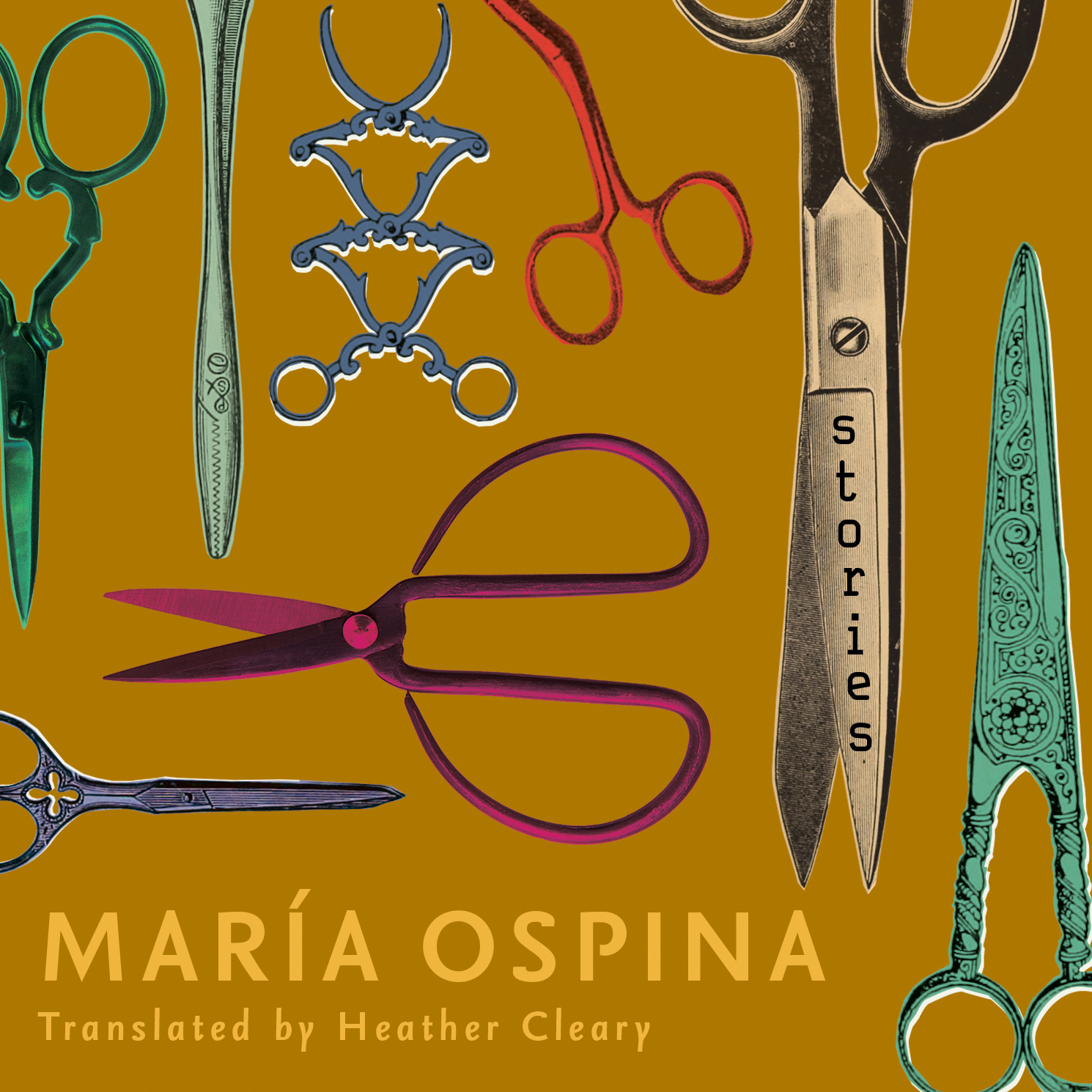

Variations on the Body by María Ospina, translated by Heather Cleary (Coffee House Press, 2021)

Contributor Bio

Heather Cleary and María Ospina

Collateral Beauty

by María Ospina

translated by Heather Cleary

So I’m left to pick up

the hints, the little symbols

of your devotion.—Antony and the Johnsons, “Fistful of Love”

“Keep an eye out for unexpected opportunities.” That was the horoscope’s prediction for Estefanía one August Saturday as she waited in the empty clinic. There was an article in the same magazine titled “The Universe is Slowly Dying,” which seemed both obvious and unsettling, so she refused to read it. As she sat behind the counter, sticking a fat needle she’d found in the drawer of scalpels and suturing instruments into the raised skin of a blister on her foot, Estefanía wondered if the message, the one about opportunities, foretold her trip to New York. Could be, though she’d always distrusted horoscopes as an act of rebellion against her mother, who was obsessed with magazine astrology. As she put her shoe back on, she immediately regretted getting carried away by the clear morning and leaving the house without socks. After completing the operation, she passed a rag across the counter, a glass display case that housed tiny shoes, hats, and other doll accessories, together with stuffed animals that had recently come out of surgery and were waiting in plastic bags to be claimed by their owners. It was almost always girls and women who came into the clinic, and their visits were getting less frequent.

She pulled the six antique dolls from their bags, getting them ready for the elegant old woman who had hospitalized them earlier that week, requesting different surgeries for each. Even naked, they exuded a dignity sculpted by the decades; even without their starched dresses made of dupioni, lamé, and lace, without the velvet or linen shoes they arrived in, they bore their seams and joints with relative vitality and pride.

“I’ve invited my friends to a special tea. They’re going to bring their childhood dolls. They’ve nearly all saved and preserved them. Since we’re all so old now, it’s going to be an antique show.”

That’s what the woman had said to her as she unpacked the box of injured dolls. Estefanía imagined a banquet of well-coiffed and heavily perfumed women, expanding their spongy flesh with succulent pastries in a grand dining room while the eternal girls with their firm little bodies avoided their gaze from tiny chairs. Maybe each woman would tell the story of her doll, the details of how it came into her life and how long her faith had lasted—how long she’d believed her doll had a soul. Maybe the pitch and rhythm of the women’s speech would change when they talked about them, and the green of their childhood voices would break through the parch of their old throats for a moment. And there the dolls would sit, indifferent to their reveries.

“You have a treasure here, ma’am. And I know about these things, I grew up in this clinic and I’ve seen it all.”

In the thick intake book, an archive of the past fifteen years of doll diagnoses and treatments, Estefanía wrote down symptoms as the woman described them to her. Her handwriting seemed clumsy and profane beside the neat letters of her grandfather and her mother, who had been in charge of the registry before her.

“Leonor, who belonged to my cousin Leonor, needs to have her face redone because her eyes and lips have faded. I do store them carefully, you know, hidden away so no one touches them. Under my bed, wrapped in tissue paper. Beatriz, this one with the jet-black hair, her arm is loose. She might need to have her rubber replaced where it’s torn. Ingrid, well, she’s not as old as the others, but she belonged to my daughter’s German friend. I made the mistake of giving her to my granddaughters for a little while, and look at her hair now, all uneven because they got it in their heads to cut it, just look at this mess. Awful. She’ll need a hair transplant. And please, something of quality.”

“Don’t worry, I have the perfect thing. We have a bit of the hair my grandfather imported from France years ago, when they still made it. It’s a pretty color, light just like this.”

“Perfect. I’d like it long, to her shoulders. Don’t worry about the cost, as long as it goes with her skin tone. And María Inés, look at this beauty, she’s from England, turn of the century, look at this little hook she has in her back, just look, she nods yes or no when you pull it. Look, look, she’s saying ‘No, no, no!’”

Estefanía imitated the woman’s peal of laughter. It had been a long time since she’d been able to laugh like that, about those prosaic things that make people howl as if there were some unforgettable joke hidden under the surface.

“Isn’t she divine? This finger is broken, it needs to be plastered and refinished. Her nails should be repainted too. And look at Shirley Temple. My father gave her to me back when we lived in England and went to see her in a movie, one of the first ones she did as a little girl. Of course, how would you know anything about Shirley Temple? She was a child actress, a big movie star in the thirties. Adorable, with golden curls just like this one here. When she became famous they made dolls of her. They were all the rage. I’ll never forget the day I opened the white box she came in. I was so excited I almost died. This one is a real collector’s item. She needs to have her leg fixed, it started turning the wrong way. I’ll bet it was the girls, they must have taken her out of the box without permission.”

The old woman grabbed the doll’s leg and forced it back to center.

“And this Arabian doll, or, well, I’m not sure if she’s Gypsy or Arab, but she’s a gem, just look how fine she is. She’s from France. She belonged to my friend Lucia, who lived in Vienna for a while. She was meant to have some strange name, Lucia told it to me on her deathbed, but it was impossible to remember so I baptized her Lucy. She told me she returned from Europe by ship, and when she reached the Magdalena River, she stood on deck with the doll in her arms so she could see the whole view. This was back when the Magdalena was a different river, a real beauty. Before it turned into a shallow sewer. So as you can imagine, Lucy has seen it all. The Seine’s cupolas and the monkeys and deer along the Madgalena. An absolute gem. You’ll need to fix her toes, too, they’re all cracked. And to straighten this eye, it wanders to the side.

Estefanía had promised to have them all fixed up by Saturday at noon so they could attend their tea that Monday.

“I’m so glad I finally managed to come in. I’ve been passing by this place for more than a year and thinking I absolutely needed to, but I’m only just getting around to it. I finally made it out to take care of my friends. I call them that, you see, my friends, because just imagine how long we’ve lived together. I saved more than a few of these friends from the ones with flesh and bones who had no idea what to do with them and nearly left them to the maids.”

As she waited for the owner of the most distinguished specimens to have passed through the Reyes Family Doll Clinic since Barbie and other products made in China flooded the market, Estefanía imagined being the housekeeper of a woman like Doña Cecilia. She’d have a light-blue uniform and a starched apron and might feel embarrassed about wearing them out in the street. She would spy on the meals served in the fine lady’s dining room through a little window in the kitchen door. When the leftovers from the afternoon tea came back in, decimated, she’d polish them off. Maybe she’d even sneak a pastry or two before they made their way to the grand table. Then she tried to imagine, but could not, what it would be like to have that job in New York, where an upper-class woman like Cecilia would have more money and who knows what customs. Maybe the same ones. She remembered the horoscope she’d read earlier. It might have been predicting an imminent trip to New York. Maybe it was foretelling the arrival of a buyer for the clinic’s storefront. Or that she would get her visa. She wanted to believe that all this radiated from the faint lettering of a magazine horoscope.

Estefanía had promised her cousin Shirley they would spend that Halloween together in New York. She’d said it less out of conviction than desire. It would be their first Halloween together since Shirley moved there two years ago, after finally receiving the green card her father had applied for a decade earlier. Estefanía had announced that she’d already figured out her costume for the party. She was going to be stray dog. She’d wear her hair all dirty and tease knots into her curls so it looked matted.

“I’m going to hang a sign that says ‘Hi, I’m a stray dog’ around my neck.”

Shirley had told her that there weren’t any stray dogs in New York. That no one would understand her costume. That she would have to explain too much, and that people would think she was crazy. That she should pick something less depressing.

“Hi, Aunt Martica. I opened the clinic early today because there’s a customer coming to pick up an order. It’s the craziest thing, I forgot to tell you, a collection of antique dolls. A real treasure. My grandfather would have died of excitement to see them restored. So yeah, I close up at noon today. I’d be happy to go with you if you come get me. I can’t wait to see your new look.”

Her Aunt Martica, Shirley’s mother, promised to pick Estefanía up on her way back from the prison where she was visiting her most pampered client, a businesswoman who had been caught storing supplies for processing cocaine in one of her warehouses. Martica was manicurist and masseuse to a long list of clients she’d built over years of hard work. She specialized in nails, firming and slimming massages, serums and secrets. After countless massages and many years spent developing strong arms and a soft body to cushion the hands and feet of others, Martica had managed to ascend to the ranks of the triumphant middle class. She did so well that she was able to pay for Estefanía’s high school after her mother died, and had promised to help her pay for a trip to New York to study English now that she’d graduated. With Shirley there and her aunt’s offer, Estefanía nurtured the hope of going, at least for a while.

That afternoon, Martica was going to show Estefanía her new face. Her return to some kind of youth. The plastic surgeon who sent her clients to Martica for post-liposuction massage therapy had given her a new face for her birthday a few weeks earlier. Instead of the free facelift that she had originally been promised, Martica had received an even bigger gift as she slept peacefully under anesthesia. The doctor had sculpted her a slimmer face with a pointier nose, higher cheekbones, and a smoother jawline. A welcome face, but not the one she’d requested. After two weeks of recovery, Martica still had a few bandages wrapped around her head, but the swelling had gone down almost completely. She wanted Estefanía to be one of the first to see her, now that she was ready to reenter the world.

When she’d finished the magazine with her horoscope, Estefanía opened her grandfather’s copy of Don Quixote, which always sat right next to the accounting books on the shelf. She had decided to read it the week after she graduated high school, but skipping around, picking chapters at random. When she was little, her grandfather used to tell her what was happening in the chapter he was reading on those Saturdays she spent with him at the clinic. She opened to one titled “Concerning what befell Don Quixote on his way to Barcelona” and wanted to believe that it was another sign of her impending voyage to unknown lands. When the phone rang again, she figured it had to be the woman with the dolls letting her know that she couldn’t make it in. After all, she was about to close. But instead she was met with the deep, halting voice of a man with a strange accent asking for the Reyes Family Doll Clinic. He explained that he was calling from the United States. That he was employed by Saint Ignatius of Antioch Church in New York, and that he’d found the clinic’s information online after a friend from Colombia recommended it to him.

“I’m looking to buy figurine parts and antique dolls for our altar.”

Estefanía tried to adopt a secretarial tone. She explained that the clinic only repaired children’s dolls and stuffed animals. She could get him the number of one of the antique shops in the neighborhood, though.

“You see, what I’m really looking for is colonial saints, but that’s not all I’m interested in. I’m also looking to buy all sorts of antique dolls, as well as parts and pieces. Perhaps you could help us find some.”

He promised generous compensation. Estefanía told him she probably had a few things that would interest him. She had to look. She wrote down his email address so she could send him a list and photos of the items. Antonio Pesoa had an Argentinean accent and the voice of an ascetic hermit speaking for the first time in ages, from the confines of a small cave.

Before wondering whether the call might be a prank, Estefanía thought of the money the deal would bring in. Of the chance to finally get rid of the inheritance of limbs, eyes, and hair that her grandfather had left to her mother, and her mother had left to her and her brother. Juvenal had already been informed of the clinic’s impending closure, and Martica was trying to find him another job. Someone would buy the storefront sooner or later. And if she got her visa, she’d finally make the trip to New York. She’d go see Shirley and sign up for the English course she’d found in Queens. She’d learn the language. She’d stay in New York for good and eagerly await Martica’s visits twice a year. She would start to believe in horoscopes.

In the back of the shop, a teddy bear, a doll with a chewed nose, and a legless Barbie with red hair awaited Juvenal’s intervention. After a brief but intense struggle, Estefanía opened the door to the small storage area on the far side of the room for the first time since her mother’s death. The drawers of the dresser to her left were marked Porcelain Parts, Clothing, Face, Religious, and Shoes in her grandfather’s neat hand. On the other side of the room was an old counter piled with arms, legs, torsos, and shopping bags full of blond heads, as well as heads for teddy bears and stuffed dogs, hands, and plastic hips labeled flesh-colored, a euphemism for the shade of white that all the dolls coddled by the little girls of Bogotá were painted. Several rolls of fabric and one of synthetic fur gave off a smell of mothballs in one corner.

“Neither of them ever threw anything away.”

With the first arm Estefanía lifted from the pile of amputated surplus, a large eye fell out and rolled across the red tiles toward a corner of the little room. When she bent down to grab it, she noticed the green and black stripes of its irises. The glass had cracked a little bit, but only in the back, so the fissure wouldn’t show when it was set in a doll’s head again. Estefanía recognized the old technique of painting on glass. They didn’t make them like that anymore. These days, eyes weren’t three-dimensional or removable, they were just drawn onto the plastic, depriving the dolls of the freedom of peripheral vision and the ability to look nervously this way or that to meet or evade the gaze of their owners. Children are spoiled by the eyes they do today, she thought. They promised the security of a gaze always there waiting for them and taught them to expect they would always be special. That’s why she was never going to have kids. Even that eye of yesteryear might bring her good money in New York. She stuck it in her pocket on her way to see what the dresser held.

In a drawer marked Antiques she found three dolls wrapped in tissue paper, which she removed carefully. There was a gypsum doll the length of her forearm, with black hair, a round face, a mouth pursed in the shape of an o, pale pink cheeks, and flawless skin, bundled up in a shawl and matching dress. She looked like a stout woman from a town in the Andes ready to set up a stand in the market square, but the tag hanging from her wrist read Germany, 1870. The next one she unwrapped was naked. Its pubic area was made of rough canvas, its public areas of the finest porcelain. A pair of legs that turned into porcelain at the knee and ended in black high heels hung loosely from its soft torso, in danger of coming unstitched. The doll’s arms were in good shape, with the exception of a crack in the palm of one hand and half a finger that had broken off. Its lips were pursed on the verge of a pout, and a few teeth could be seen in the space between them. It had blue eyes and long lashes, and dark hair painted on to just below the ears, as was the style. France, 1918. Despite her flagrant nudity and the anonymity of decades spent in a dark drawer, there was nothing sinister about her. She seemed headstrong but also polite. From a small box Estefanía removed an androgynous baby in lace swaddling that even encircled its head, forming a kind of crown. The head was the only notable part of the body. Bisque porcelain, read the tag written in her grandfather’s hand. Sheathed in lace, the doll’s face was dominated by two enormous gray eyes, shiny and open wide, surrounded by long lashes that heralded a future of intense grief. Vienna, 1901. It begged to be taken out for a stroll by a nanny, around a city from a different era. It could certainly play the baby Jesus in a Manhattan church at Christmastime.

Other items from her grandfather’s collection of antique remains appeared in the list Estefanía sent to the strange Argentinean who had called that morning.

- Black infant in bisque porcelain, crack in one leg and small hole in one heel. Rubber intact. Missing head. Chubby. Tag reads France, 1926.

- Assorted parts: one pair of eyes, painted wood with inlaid glass irises and pupils. Four pairs of glass eyes in different colors. Single eye, lightly scratched on the back. One pair of porcelain arms attached to cloth. One pair of medium wooden feet. One pair of plaster feet (5 cm long).

- Other: miniature perfume bottle in blue glass; embroidered knit socks for a large doll; small ivory fan with floral design; white leather gloves with black embroidery; small metal mirror; leather-bound doll’s diary, can be opened; porcelain lapdog with brown fur and an open mouth that reveals a painted tongue inside.

“Come take a look, sweetheart, and tell me what you think.”

From inside the storage room Estefanía heard Martica’s voice and went out to meet her.

“Gorgeous!”

“Sometimes I think this royal face doesn’t go too well with the body I’ve got.”

“You look great, Aunt Martica.”

“The swelling still needs to go down a bit more before I look like one of those fancy dolls you said someone left here.”

As she climbed into Martica’s car, Estefanía noticed something in her pants pocket digging into her leg. It was the glass eye she’d forgotten to leave in the pile of old figurines when she ran out to see the other doll in her life.

Estefanía spent the next week waiting for the woman to reclaim her dolls. A few orders came in, which she received with great efficiency and which kept Juvenal busy for a while: a teddy bear that vomited fill from a tear in its shoulder, three bland little dolls who had ended up in a child’s beauty parlor and couldn’t pull off their new punk hairstyles, and one of those dolls that pee, which needed a new torso because its owner had poured drain solvent down the tube that ran from its mouth to its groin. But the date of the tea had come and gone, and the elegant dolls remained behind the counter. Inclined to tragic thoughts, Estefanía imagined their owner in a casket, seized by a rigor mortis of longing.

On Friday, she decided to call the number the woman had left on the receipt. A housekeeper informed her that Doña Cecilia would be traveling for an unspecified period. When Estefanía explained that the clinic would be closing soon, for good, and asked what she should do with the dolls, the woman disclosed that her employer had been in a nursing home since the weekend before, that her son had returned from abroad to take her there. The housekeeper offered to ask about the dolls and promised to have an answer for her the following week.

Estefanía looked through the glass counter at the dolls’ faces, all wrapped in plastic, and knew she needed to save them. They didn’t deserve to be in that chipped display case for one moment longer.

Estefanía:

Your message has given us immense pleasure. We wish to purchase all the items you offer. Though some of the objects you mention do not fall under the rubric of religion, they will suffice just the same. We can offer you three hundred dollars for the lot. Should you be interested, we would need to determine a means of shipping the items to New York. I’ll look into different parcel delivery services this week and follow up with you. I wish I could travel to Bogotá to pick them up, but that is a fantasy. I await your reply.

Antonio Pesoa

Dear Estefanía:

I forgot to ask you in my last email if by any chance you have a ventriloquist’s dummy among the items available for purchase. Please say you do! Let me know as soon as you can.

A.

Having called the number left by Doña Cecilia for two weeks with no response, Estefanía decided it was time to find asylum for the exiled dolls. She’d searched for the woman’s address so she could bring them to her home, but it wasn’t listed in the phone book. Maybe she had told her the story of each one in so much detail because she was leaving them to her. Maybe she cried out for them in the drugged stupor of afternoons in the psychiatric ward and everyone thought the names were yet another symptom of her malady.

After another two weeks of waiting and several failed calls, Estefanía accepted the dolls as her irrefutable inheritance. That night she dreamed of the six of them adorning a gilded colonial altar. In each section of the altar was a doll wearing a starched saint’s gown and tunic, with a rosary dangling from hands recently repaired by Juvenal. Antonio entered, dressed all in black with a woolen cap covering his bald head. He seemed to be floating, as if he was being pulled by a string from his belly. He knelt at the first pew. Estefanía stepped inside the church and tried to approach the altar, but a furious priest threw her out in unintelligible English. Antonio said nothing; he just looked at her, deeply moved. Estefanía stood in the doorway, sobbing next to a leper reeking of urine who begged for alms, and realized she was in the Church of Saint Frances in downtown Bogotá, where her grandfather used to take her when she was a little girl.

Dear Estefanía:

It would be wonderful if you sent everything with your aunt next week. It would have to be packed well so none of the little pieces break, given how delicate they are already.

The loose eyes! Yes, we want them, absolutely. And we’re just thrilled about the other dolls. We could pay you four hundred dollars for them, if that figure seems fair to you.

They must be strange treasures, indeed. But of course, things worth treasuring tend to be strange. They’re the ferment that escapes the mold.

I like your idea of decorating an altar with these alluring dolls.

Make sure they shine according to their essence.

I’m dying to get my hands on a ventriloquist’s dummy from the colonial period. They’re very hard to find. I want to propose a kind of religious-didactic performance to the other priests, between a ventriloquist (dressed up as a saint or a virgin) and his doll (which could play the role of angel or a soul, or something like that).

I can pick up the delivery and pay your aunt directly, as you mentioned. My phone number, so she can call me when she gets to New York, is (212) 945-3850.

Please write back and tell me more.

Warmly, A.

P.S. Thank you for sharing your dream with me. In my version, were my dreams to shimmer, I would attack the priest, tie him to the column, and force him to perform hara-kiri, then I’d take you to see the newly canonized dolls and the ventriloquist playing a soul in purgatory. But don’t take me seriously. I haven’t slept in days.

A fine rain misted the city on the September morning when Estefanía took Doña Cecilia’s dolls out of the counter display and carried them over to one of the long surgical tables. Juvenal was working at the other one, sewing a new pair of ears onto an enormous Saint Bernard. One by one, the dolls allowed themselves to be laid flat. Their naked bodies revealed their new precarity. Estefanía walked over to the storage room, opened the drawer marked Clothing, and pulled out a bundle of dresses wrapped in tissue paper. Leonor looked pretty in a blue satin dress with a petticoat. The lace tunic worked for little Beatrice. The pleated dress with short sleeves was good on Ingrid, topped off with a simple white coat. And so on. She found something to cover each of them, so they wouldn’t have to travel in just their inner majesty. Antonio would need to find them more suitable dresses for the altar. She pulled a few small rosaries made of orange and rosewood from the drawer of religious objects and put one on the arm of each doll. She packaged them one by one in bubble wrap and laid them in the boxes she’d gotten for their journey. Then she dusted off the dolls in the storage room and the body parts she’d promised Antonio, resting each one on a bed of foam scraps and paper shreds.

The sun was just rising in Bogotá when Estefanía went to the airport with Martica. Martica made the trip to New York when the big department stores had their sales. She traveled light and came back with two suitcases full of clothing her clients in Bogotá had ordered, which she sold to them with a commission that covered her expenses and padded her savings account. She used to stay with her sister, the one who worked at a factory in New Jersey assembling tiny pieces of airplane motors, but ever since Shirley moved to New York, Martica has been staying in her daughter’s apartment.

The two boxes with the dolls and other objects for Antonio were selected for inspection by the antinarcotics unit as Martica waited in the long line to check in at the airport. One police officer had a young dog that wagged its tail furiously as it searched the boxes for cocaine. The officers urged it on, trying to get it to find the valuable powder, but the dog showed no interest. Confirming one last time that the shipment contained no illicit substances, one of the police officers took out the Arabian doll, unwrapped it, licked his index finger, ran it along the doll’s leg, and returned it to his mouth. When he didn’t taste the alkaloid he expected to find diluted in its skin, he gave the final order to close the boxes. A few days later, Martica called Estefanía to say that she’d delivered the boxes to Antonio and had the money in hand.

“All he said was thank you, ma’am, and added that I have a lovely niece. He also said he wants to meet you, sweetheart.”

Crowned, victorious one:

(That’s the etymology of your name, did you know?) I received the beauties you sent, despite the mishaps. If I were an airport police officer, I would have confiscated them all without the help of any dog and made a run for it. You can rest easy, your grandfather’s treasures will be venerated here. The doll that moves her head to say yes and no arrived with an injured hand. Could she be the one the dog sniffed? Perhaps the gesture rattled her humors.

I thought about her yesterday, and also about you, and about matters of the flesh, because I almost took a little old lady’s finger off at the gym. I was using one of those weight machines; she stuck her hand in, and I smashed her finger. We had to call an ambulance. It was absolutely pulverized. She’d stuck it right between the weights. There was blood everywhere, which wasn’t entirely a bad thing because it snapped all those people staring at themselves in the mirror back to reality a bit. The ambulance arrived forty minutes later and no one got out so I went to see what was going on, and the girl behind the wheel was busy putting on lipstick. Anyway, the eternal mysteries of athletic life. Good Lord. The old lady was quite stoic, thank goodness. But who puts their hand right where weights

are going up and down? I told her I was sorry and that I’ll never go back there. And to think, I’d managed to drag myself to the gym for a couple of weeks straight. I blame it all on one of those guys who sells exercise equipment on television. This one has a disgusting blob of resin that he claims is pure fat, and he calls it “Mr. Fat” and goes on and on about how it lives inside you. Have you seen him? I was so disgusted that I paid for a year-long gym membership in advance. But I can’t go back after the incident with the old lady. I’d rather be here, in my cave, caring for my injured doll.

Your aunt said you might visit New York soon. When you do, I’ll take you out for tea and we’ll have some delicious pastries filled with peaches from a distant island in the Japanese archipelago. And talk about any old thing.

I’ll send you photos soon of these contemplative girls in their new home.

Write to me. About whatever you like, anything will do.

Of late, my nights consist of trying to keep my thoughts at bay—they’re like search dogs with a deafening bark.

Thank you, your majesty.

Warmly, A.

Estefanía reread the message. She wished it had been written by hand. Her aunt had told her that Antonio was extremely shy, one of those men whose silences reveal more than what the rest of us know. Estefanía thought of a wild horse running across the plains of Asia, of those four-thousand-year-old pines that still grow on the hills of the Middle East. Antonio must be something like that.

The liquidation of the Reyes Family Doll Clinic lasted four weeks. The space sold quickly and for a good profit. A developer was buying up the whole block to build luxury apartment buildings like the ones going up all over Chapinero. Juvenal decided to drive a relative’s taxi while he waited for a job with one of Martica’s clients to come through. Estefanía took the things she wanted to save: a couple of paintings of European dolls sitting in chairs in a park in spring, which her mother had hung in the operating room; the collection of miniature hats for sale inthe counter display; the business’s sign and accounting books; dolls that were left over after the liquidation; Don Quixote. Some pieces of furniture and other remnants were donated to a school for the blind a few blocks away. The rest went to the garbage pickers. When Estefanía locked up for the last time before turning the shop over to its new owners, it occurred to her that one day she’d come back from New York and not recognize the dirty, rundown corner of her childhood, and she would feel an emptiness.

In the airplane headed to New York, as she flipped through the blank pages of the notebook Martica had given her for jotting down the contacts and friends she would make in her new life, Estefanía wondered again what might be behind Antonio’s long silence. It had been weeks. He’d never answered the letter she sent him with the details of her trip, in which she repeated her interest in their Japanese tea and promised to bring him a sweet mango so he could experience for the first time what it was to drink the fruit’s pulpy juice from a tear in its skin. Or the next one, in which she’d copied the first and asked if he’d received it. Or her last one, written just days before she arrived at her cousin Shirley’s apartment in Queens. Had Antonio been scandalized by the image of a mouth sucking on a mango? Maybe it had stirred him in his strict celibacy. Had he been disappointed by the bourgeois dolls, which Estefanía sensed were hardly worthy of an altar? Or maybe he’d had an accident. In his last letter, Antonio had mentioned a pain in his chest, terrible fatigue, and shortness of breath. That’s why she was bringing him a mango. Martica always said that nothing kept a heart healthy like a mango.

The mango slowly rotted in Shirley’s refrigerator. A few days after throwing it out, Estefanía went looking for the address Antonio had given her in one of his first emails. She took the Manhattan-bound subway Shirley had told her to and got off at Twenty-Third Street and Park Avenue. She walked along Twenty-Third until she reached Second Avenue, then headed north to Twenty-Fifth. She passed a Laundromat, an Irish pub, the front steps of apartment buildings, and a storefront that announced itself as a Christian Science Library, but she didn’t see a church anywhere. The building marked 228 was a pink multistory residence. Estefanía walked around the neighborhood looking for a church, but the only one she found was a few blocks away and had a sign out front that read, “FOR SALE. Immediate Occupancy.”

She spent the next week visiting churches in Manhattan. She’d enter just as mass was ending, study the altar, and ask each priest if he knew Antonio Pesoa. The first churches were near the address he’d given her. But as she started visiting others further from the neighborhood, she realized she was going to spend the winter looking for him. And for the dolls.

On Halloween, Estefanía dressed up as a stray dog to go to the party Shirley had invited her to. A few gringos asked her to explain her costume, and she pointed to the sign hanging from her neck, which read “Hello, I am a street dog (girl)” in her shiny new English.

~

Estefanía’s ecclesiastical investigation came to an abrupt end in January, when Martica told her on one of their daily phone calls that she’d gotten a package from New York that had been sent to the clinic and then forwarded to her. Inside was a box wrapped in paper with drawings of monsters and Japanese characters on it, and a letter she read out loud.

Dear Estefanía:

I’m writing to let you know that Antonio Pesoa died at the end of September. As the friend in charge of distributing the objects he left behind, I wanted to inform you that I found this box in his apartment, ready for the post office and addressed to you (I hope this is still your address). He spoke of you when he showed me the dolls he’d bought from you. (I was the one who told him about the clinic; I lived nearby when I was little. My mother brought several of my dolls there for repairs. It’s a shame I never went inside, though I always meant to.) Antonio would shut himself up in his apartment with them for hours. He didn’t go out much toward the end. He didn’t want to see us because he was ashamed of his illness, so they became his companions. He was working on a photo series of his neighbors from the building sitting among the dolls and parts you’d sent him. He told me a while ago that he was writing an epistolary novel about a fugitive who hides in a seminary on Manhattan’s West Side and tries to find pieces for the figurines in the adjoining church. In the novel there was a girl who sent him those things from far away.

I haven’t found the manuscript among his files, but if I do, I’ll make sure it reaches you. For now, I’m sending you this package, which he left for you before his heart rebelled.

A hug from the friend of a friend,

Claudia Galindo

“Open it, Aunt Martica. What’s in the box?”

“It’s a book, sweetheart. An old book in who knows what language.”

The old leather-bound missal could only be opened to a page in the middle; all the others were stuck together. There, in a hollow carved out of the pages, the head of an antique doll rested on a bed of dried flowers, protected under glass. A dark-skinned face nested in a fragile book, surrounded by unfamiliar and unintelligible letters. Her eyes moved nervously back and forth when the book was opened to reveal her.

In the photo of the gift that her aunt later sent, Estefanía recognized the head as Lucy’s, the doll that had crossed the Seine and then the Magdalena nearly a century before, in the arms of well-bred girl on her way to provincial Bogotá. The doll that had declined the invitation to rot during its passage through the brutal heat of Honda, that had crossed the Andes on the back of a donkey and had withstood seventy years of being looked after by two upper-class women. Until Estefanía and Antonio came along to disrupt her years of peace and mothballs.

What had become of the other dolls, of the arms and eyes that found no place on any altar? When she buried her mother, Estefanía had come to understand that the living have trouble with the things left by their dead. Had Antonio’s friends scooped them up and set them on their shelves? Were they in the window of some antiques shop? She even imagined them in a landfill somewhere outside New York, tiny arms sticking out from a mountain of plastic, old shoes, garbage bags, fruit rinds, office files, and computer screens. She thought of their little doll eyes fixed on the waste from silicone implants, syringes, yogurt cups, lunch boxes. Those antique glass eyes transformed into the inert filling of a dump in a country full of trash. Witnesses to the disintegration of bones from countless chicken wings that would decay faster than them. Eyes with no audience to witness the putrefaction they reflected.

She felt better thinking of the little head protected by the green leather binding of an old book that had made its way to Bogotá, searching for her.

“Aunt Martica, will you bring it with you when you come?”

The seven Claudia Galindos that Estefanía found on the internet—a beach volleyball player from Bogotá, a Mexican pastry chef, a Canadian lawyer, a sociology professor in Bolivia, an actress living in Miami, and others whose occupations were impossible to determine—never answered her emails.

~

With the exception of two weekends in February when snowstorms paralyzed the city, Estefanía spent every Saturday and Sunday that winter and spring visiting antique shops in Manhattan in search of the other dolls. When her student visa expired early that summer and she needed to head back to Bogotá, she still had nine shops left on the long list she’d compiled for her pilgrimage. Lucy stayed behind, presiding over Shirley’s apartment from her pagan altar. Estefanía promised them both that she’d be back soon and slid the list of the remaining antique shops into the book. So she could keep searching whenever she returned.

“Collateral Beauty” is a story from María Ospina’s forthcoming collection Variations on the Body, translated by Heather Cleary (July 2021, Coffee House Press).

Published on June 29, 2021