Cecily Aching Best

by Cecily Parks

Learning the name for something can resemble care. So, for example, if I learn that the autumn explosion of tiny purple flowers in my front yard is a Fall Aster, I notice the Fall Aster when it appears elsewhere, grow intimate with a plant that for most of the year is dull and brushy and clamors for nothing. If the profusion of showy radiated purple is the flower’s way of securing my attention, then its name is what makes my attention endure.

Aster comes from the Greek word for star and, once upon a time, aster was the word we used in English to refer to stars. Knowing that the aster is the star’s namesake spurs me to compare them, and my mind easily finds the filaments of likeness. Each flower makes a luminous burst in the dark green.

To consider the aster is to participate in a simile. The most interesting similes tether entities farthest apart: a brushy, briefly blooming shrub and a star. These similes give the subject (what scholars call the simile’s tenor) a richer, hitherto unconsidered existence. When Emily Dickinson says of a bird’s eyes, “They looked like frightened Beads, I thought,” we see the bird as both a beast and bejeweled.

A name derived from another can be a simile, posing a question that a woman can spend a lifetime trying to answer, because namesake implies an obligation to her precursor, the original her replica, the song to her echo. In Robert Frost’s poem “Maple,” a girl’s mother names her Maple, then dies. Frost’s similes rarely startle, but the one that forms the premise of the poem does. The name remains a cipher even to Maple’s father, who admits, of his late wife’s choice of name, “I don’t know what she wanted it to mean.” The name opens a space to be filled by answers to the question of how Maple is like a maple tree, a question the dead mother can’t answer.

Which brings me to my life’s question: How am I like Cecily? Maple’s namer is dead. The woman I’m named after is dead. Like Maple, I think, I want assurance that my name attaches me to the world, its trees, asters, and women.

A childless newly married American woman in the 1970s, my mother found herself with more time on her hands than she liked when she followed my father to Hong Kong for his job at an international banking firm. She’d left her job as an executive secretary in Manhattan and now tearfully smoked cigarettes in the kitchen of a high-rise apartment overlooking the harbor, wondering what her purpose was and waiting for my father to come home. Long-distance charges for phone calls were punishing, so she called her parents in Long Island once a month and her friends back in the States not at all. She slowly filled her days with wifely expatriate pursuits: letter writing, flower-arranging classes, watercolor classes. She slowly made friendships with other wives who had been adrift in her predicament and steered themselves out of it.

What made my mother’s arrival in Hong Kong perhaps more complicated was the fact that Hong Kong was a kind of homeland for her. Her father, the son of a Scottish marine police officer and a half-Chinese wife, was born there. Her grandmother Edith and great-grandmother Cecily were buried in the oldest Catholic cemetery in Hong Kong, where my mother cleaned grime from their graves. There my mother pressed a wet rag and water into the depressions of each letter of Cecily’s name before leaving gaudy flowers, bought at a cemetery stall. During those ministrations, notions of a one-day daughter named Cecily lodged.

Who was she? My mother’s father possessed a single childhood memory of his grandmother: she was the Chinese woman who once appeared in the kitchen of his family home in Hong Kong and left. Or that was what I was told, which was different than what was true. To me, the memory revealed that my grandfather never got the chance to know his grandmother and learned instead to think of her as a fleeting glimpse of race and gender, a someone who was not white and British, as he’d been taught to be and told he was. Over time, the memory also suggested that it may have been easier for my mother’s family to reference the glimpse of the woman nobody knew because at some deeper level she was almost longing incarnate, and it was too painful to admit to longing for her.

Her face, what she wore, how long she stayed, what language she spoke, whether she touched her grandson’s hair or cheek or hand, what home she returned to after visiting her daughter’s children: these are lost. Cecily wafts away, turning into a shadow or a shift in the air of the hallway, or the sound of footsteps leaving. Cecily, from the Latin caecus, means dim-sighted, or blind one: who I am when I try to see my great-great-grandmother’s face, the blink of her eyes, the exact shade of her dark hair, her dress, her laugh, the lines around her mouth, the shape of her fingernails. My life’s simile won’t resolve. How can I be the aster to her star? She is so far away in the firmament that all I can do is conjecture about her, using facts that sketch a biography but not a woman.

In 1860 a Chinese girl is born in a coastal port that will, after the Opium Wars, become a bustling hub for Chinese-European trade. Her family moves north to what is now called Xiamen, a busier port where the South China Sea’s sting mixes with the scent of exports: stacks of cut and branch-stripped fir, pine, and rosewood sold as timber, or the oolong tea leaves from Fujian that smell like orchids. The ocean brings salt, wind, and wetness to the air, her fingers, the pocket of skin behind her ears, and the stray dark strands of hair escaping the knot they’re twisted into. Maybe always watching the European boats entering the harbor makes her believe that somewhere someone is sailing toward her, his ship ripping the ocean’s seams. Then he appears. A British tea merchant from India named Cadogan Best, he finds her Chinese name too difficult to say, so he calls her Cecily instead, because it’s a name he knows, the name of his aunt or cousin, or the name a girl he met outside of St. Paul’s Church in Agra, her yellow hair alight in the sun.

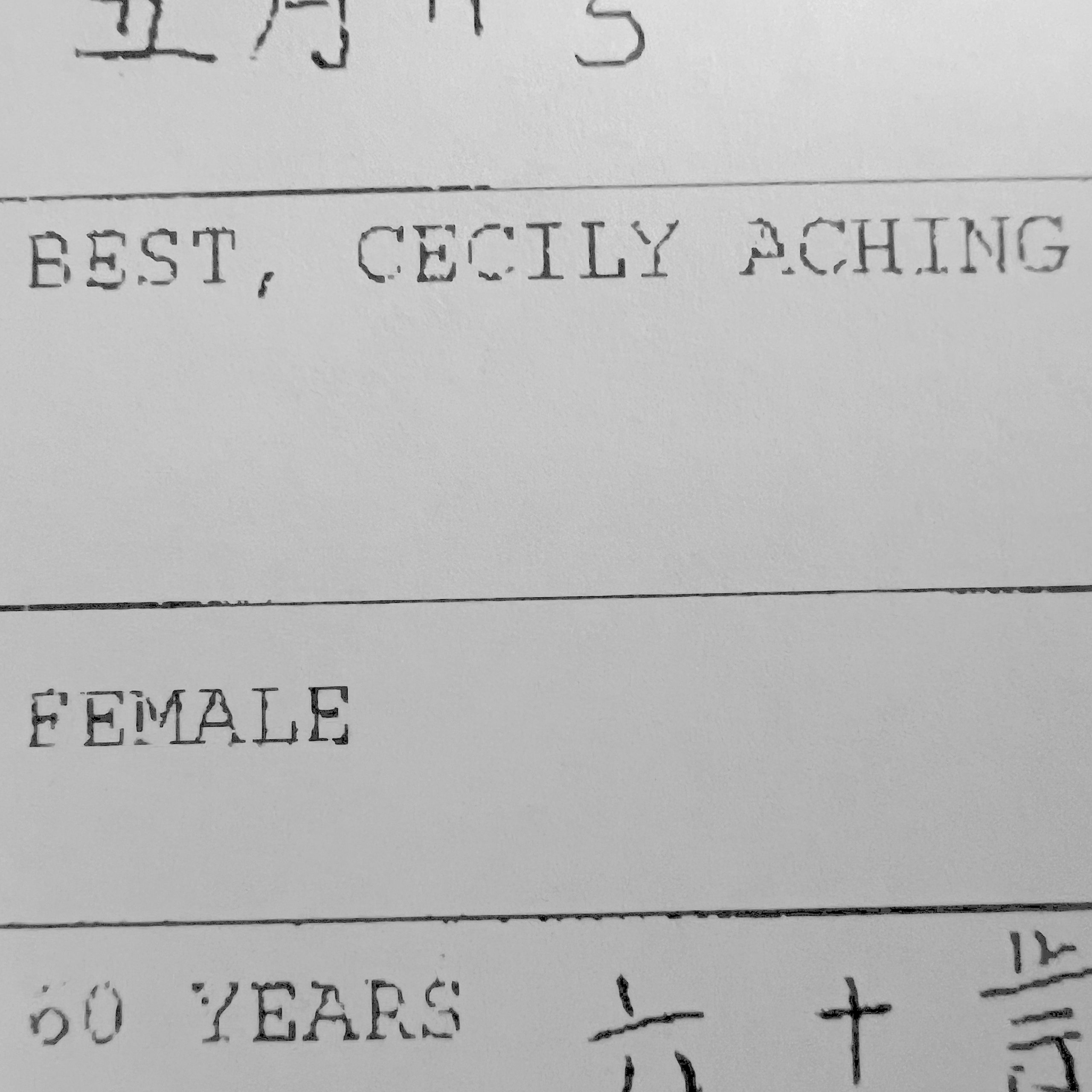

In the colonial era, adopting an English name would have been a common practice for a Chinese woman in Cecily’s position, attached to a British man who may have felt entitled to name her as he pleased. At that time, European men often formed provisional relationships with local women but didn’t officially marry. Some women, as Cecily eventually did, adopted the men’s last names. By the time my great-great-grandmother’s name is documented in writing, it’s English, as Cecily, or Cecily Best, or Mrs. Best. On her death certificate, her name appears with a Romanized middle name as Cecily Aching Best, tempting me to read her transformation from a girl with a Chinese name to a woman with an English one as an expression of pain.

Cadogan had four children with Cecily, brought them all to Hong Kong, and then abandoned them. It was said that he was bankrupt and fled for a string of British colonies, first Australia and then the Seychelles, where he died. His death certificate, witnessed by an assistant forest ranger, lists my great-great-grandfather’s profession as “None” and his residence as Moyenne Island, the twenty-two-acre island owned by his sister. It is said that she later turned Moyenne into a refuge for unwanted dogs.

Under the death certificate category “Whether Married, a Widower or Widow,” Henry is described as “Single,” because he never legally married the Chinese woman who now went by the name Cecily Best and was solely responsible for the care of four children in Hong Kong. As a Chinese woman with half-Chinese children, she would have been shunned by both the Chinese and the British population there. She likely commanded the social status of a prostitute. She placed my great-grandmother Edith in a Catholic orphanage dedicated to the care and education of mixed-race girls, and Edith eventually married a British man, but that is another story.

Cecily’s story is one that I’d hoped to excavate from traces: handed-down memories and official documents. As a scholar trained to find textual evidence, I’ve held photocopies of my great-great-grandparents’ death certificates for over a decade, as if they were fine old wines that would, when brought out of a cellar and into light, reveal levels of complexity and revelation. Who hasn’t returned to a text later in life—the poem “[Because I could not stop for Death]” by Emily Dickinson, say—and realized that reading the poem as a forty-five-year-old is far more darkly exhilarating than reading it as a fourteen-year-old who didn’t believe she would die. The text hasn’t changed; the reader has. Subjecting a death certificate to exegesis is what I can do when the trail of inquiry comes to its end. Subjecting it to exegesis again is what I do when the trail of inquiry refuses to end.

Cecily’s death certificate is, in places, typed in English and handwritten in Chinese. The certificate still tells me that Cecily Aching Best died of bronchitis on May 20, 1920, at St. Francis Hospital in Hong Kong. She was sixty. The space for “Rank, profession, occupation and nationality so far as is known” is filled with two typed rows of eight asterisks, sixteen stars fill in the box to ensure that it can have no words. Sixteen asterisks decline to describe Cecily as Married, Housewife, Mother, Widow, or Chinese. On the gravestone my mother washed under frangipani trees, her name appears as Cecily Best.

The asterisk is that typographical star that appears in a text to tell readers that there is something more to be added or redacted. The asterisk, which also comes from the word aster, has an effect like starlight, a message from a messenger far away, maybe already gone, maybe disappeared. Cecily is a constellation that I’ve tried to navigate by for over a decade, trying to understand who my great-great-grandmother was so I can know who I should be. In her poem “[Go thy great way!]” (Fr 1638), Emily Dickinson asks, “For what are Stars but Asterisks / To point a human Life”? In my case, the question isn’t rhetorical: the stars that point my life really are asterisks, typed on a death certificate.

In her last known poem, or poetic fragment, Dickinson found in the asterisk—not the punctuation mark, but the word—a denotation of the death that she sensed nearby, writing: “The Asterisk is for the Dead, / The Living, for the Stars —”(Fr 1685). The inscribers of my great-great-grandmother’s death certificate apparently also thought that the asterisk was for the dead, and typed them as a way of indicating something beyond the confines and categories of the death certificate, the incomplete story of my great-great-grandmother’s life. In the present that I write in, the asterisk signals brokenness and an irrecoverable past.

In Frost’s “Maple,” Maple’s name remains an inquisitor as Maple ages: “Her problem was to find out what it asked / In dress or manner of the girl who bore it.” Maple “looked for herself, as everyone / Looks for himself, more or less outwardly.” Maybe Frost’s poem highlights our misplaced faith in language to connect us to the material world. Maybe it celebrates the curiosity borne out of confusion. Or maybe it affirms the capacity to accept, and even love, what the imagination makes. Maple ends up marrying a man who, before he knows her name, says that she reminds him of a tree. Frost concludes: “Thus had a name with meaning, given in death, / Made a girl’s marriage, and ruled in her life.”

There’s not just one meaning of a poem, or line, or word. Or name. When I talk about my name, I’m reading a single-word poem that, each time I return to it, yields different meanings.

Cecily isn’t my great-great-grandmother’s real name. In Chinese, her name would have been composed of a surname (the name of the family who gave her to my great-great-grandfather in a transaction whose terms have been lost to time) and a given name after it, a name specific to a daughter born to Chinese parents in the Guangdong Province in 1860. Her surname would not have been one that she used much during that time period, and her family name is forever lost. Her given name was A-Ching, though even that is a pinyin transliteration of Chinese characters in an alphabet that I have never learned.

To better understand her name, I appealed to three people: a literature scholar who is Chinese, a Cantonese teacher, and a diplomat. Without them, I might not have learned that the “A” in A-Ching has no real meaning but is commonly used in southern China as a sound filler to fulfill an expectation that a name should consist of two syllables. Of the possible characters that would have represented Cecily’s given name, Ching, I learned that the likeliest are 青 and 清 and, of the two, it’s most likely to be 青. The “A” sound, the filler sound, is 亞. So, my great-great-grandmother’s given name would have been written: 亞 青. Some would say we don’t, in point of fact, share a name. Some would say that I’m a married professor and mother of two, the daughter of a mother who had the leisure and luxury to clean the graves of her female ancestors, and that in the discourse of privilege and opportunity, I’m the star to Cecily’s aster. But how can I say so when I don’t know her, when not-knowing brims with endless possibility, is luminous? The character 青 (transliterated as Ching or Qing) means green, green grass, youth, or sometimes is used to describe the blue-green colors of the sea or the mountains, seen at a distance, a blue-green out of which she, in my imagination, will ever flicker.

Published on October 14, 2022

First published in Harvard Review 59.