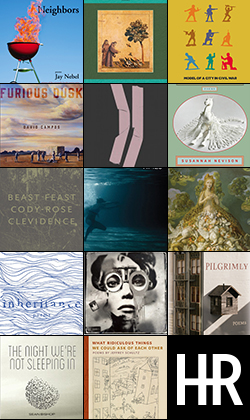

“Captured, Tortured, and Biting a Stick”: Fourteen First Books of Poetry

by William Doreski

“All poetry is experimental poetry,” Wallace Steven famously noted. Our era proves him wrong. With so many style templates available, most poems can’t help but signal their intentions in their first few lines, so the experienced reader knows immediately where they’re going and how they will get there. Journals that demand “experimental poetry” want either warmed-over Language Poetry, abrupt juxtaposition in the Ashbery mold, or a meandering pattern of lines, derived from Projective Verse. Others want well-wrought MFA poetry with sentimental delving into troubled family relationships: daughters bonding with mothers, sons feeling distanced from fathers, preferably recounted after the elder party has died.

For some aspiring (or “emerging”) poets, identity is the issue. An autobiographical mode that has evolved from what was once called confessional poetry, identity poetry underscores a particular social allegiance. The stronger young poets, including some reviewed here, invoke identity but then maneuver around the hazards of this motif. They may stake a claim on our progressive empathies, but their best poems set that aside while profitably exploring issues of imagination and culture for which poetry is the best medium.

David Campos [1] is a Latino poet who teaches at Fresno State University, and his book won the Andrés Montoya Poetry Prize, so we might expect his poems to dwell on questions of manhood, family, and the experience of growing up in a sometimes hostile West. And so they do. Add to that an obsession with food, the stigma of being overweight, and dread of and fascination with the carnage of deer hunting, and the poet risks a glut of autobiography. But Campos writes clean and starkly visual free verse, and often generates deeply telling metaphors:

My wife shifts in her sleep,

and I hear her teeth grind

like a carcass dragged

slowly over gravel.

The reader may find his poems about childhood a bit too familiar; many of them, like “Cast Iron,” are frank to the point of cruelty, and most depict situations universal in both detail and in their larger implications. His best poems, like “Museum of Natural History,” write their way into the central facts of humanness: “We are born without clothes; / for warmth we kill for skins. / And it’s cold this morning.”

Campos refers to his weight problems with a wry self-disgust, and occasionally seems willing to shed not only excess bulk but the body itself. Other poets also shape their identities by mulling over the mysteries and challenges of their bodies. Susannah Nevison [2] writes poems about breathing, about tendons, about “bodies pressed into themselves,” poems entitled “On the Physiology of the Heart” and “On the Surgical Dressing Change, in Water, of a Five-Month-Old Child.” She frequently echoes Sylvia Plath and those poets who followed Plath into the gap between the body and the spirit, where the very focus on flesh seems to risk disembodiment.

Campos refers to his weight problems with a wry self-disgust, and occasionally seems willing to shed not only excess bulk but the body itself. Other poets also shape their identities by mulling over the mysteries and challenges of their bodies. Susannah Nevison [2] writes poems about breathing, about tendons, about “bodies pressed into themselves,” poems entitled “On the Physiology of the Heart” and “On the Surgical Dressing Change, in Water, of a Five-Month-Old Child.” She frequently echoes Sylvia Plath and those poets who followed Plath into the gap between the body and the spirit, where the very focus on flesh seems to risk disembodiment.

The problem is sometimes one of address. A mysterious you means either someone else or the speaker addressing herself in that person. Sometimes it references another clearly delineated person—a child or infant—but most dramatically it is the body, addressed as a separate being, as in the prose poem “Notes to the Body,” which opens with “When you asked if I would stay with you, I wanted to say yes, I’ll always be your best girl.” Such writing, scraping the self from its cocoon, risks a terrible inwardness, but Nevison usually manages to cut her losses and end the poem—sometimes mid-sentence—before the spirit drifts off into the bright beyond. She writes fairly tight poems, some of them in prose, others in neatly patterned verse forms. Some borrow Emily Dickinson’s patented dashes, not a good comparison for any poet to invoke. Still, in many of her poems, like “Another Kind of Clay,” Nevison becomes herself in a modest but whole entity, complete and comfortable on the page.

Some poets prefer chaos to repose. Sean Bishop’s [3] poems wrestle with their lines, sometimes spacing them oddly, uncomfortably, as in the opening poem, “Terms of Service,” and at other times forcing enjambments that seem too awkward to work, yet somehow do, as in much of “Black Hole Owner’s Association.” Bishop’s poems almost become melodramatic, with closures that sometimes are hard to link back to the poems they complete, as in the second part of “To Throw the Little Bones That Speak,” which ends with the couplet “what remains // of a child’s body with its breakable bones / of how many licks until we hit the marrow.” Sometimes a grim sentimentality compromises or at least clouds these poems, usually by invoking a questionable childhood with a slightly grotesque father lurking behind it. Yet these are intense, energetic poems, sometimes compelling, with a confident if urgent diction:

Some poets prefer chaos to repose. Sean Bishop’s [3] poems wrestle with their lines, sometimes spacing them oddly, uncomfortably, as in the opening poem, “Terms of Service,” and at other times forcing enjambments that seem too awkward to work, yet somehow do, as in much of “Black Hole Owner’s Association.” Bishop’s poems almost become melodramatic, with closures that sometimes are hard to link back to the poems they complete, as in the second part of “To Throw the Little Bones That Speak,” which ends with the couplet “what remains // of a child’s body with its breakable bones / of how many licks until we hit the marrow.” Sometimes a grim sentimentality compromises or at least clouds these poems, usually by invoking a questionable childhood with a slightly grotesque father lurking behind it. Yet these are intense, energetic poems, sometimes compelling, with a confident if urgent diction:

Secret Fellow Sufferers,

our fathers are liars:

Some slick beast is breathing by our bedsides.

Down the chimney each winter a dead saint comes

to cough into our hearths a year of obligations.

By edging close to overstatement, Bishop energizes ordinary domestic scenes and casts them into deep relief.

Not all poets court this sort of peril. Rejecting any sort of dramatic diction or form, Cathy Linh Che [4] presents many of her poems as simple narrations broken into even simpler free verse. Because these are stories about her family and their difficulties in Vietnam, their escape to this country, their subsequent stories of illness, puberty, and domestic tensions, they beguile us without challenging the imagination through any particular linguistic means. As poetry most of this work is modest and memoir-like. But some poems transcend their own mode by generating a sense of the mystery of ordinary life, as do “Talk” and the first of two poems entitled “Brooklyn Interior.” The longish “Letter to Doc,” the strongest poem in the book, invokes a complex of emotions that it tries but luckily fails to subsume as “love”:

Not all poets court this sort of peril. Rejecting any sort of dramatic diction or form, Cathy Linh Che [4] presents many of her poems as simple narrations broken into even simpler free verse. Because these are stories about her family and their difficulties in Vietnam, their escape to this country, their subsequent stories of illness, puberty, and domestic tensions, they beguile us without challenging the imagination through any particular linguistic means. As poetry most of this work is modest and memoir-like. But some poems transcend their own mode by generating a sense of the mystery of ordinary life, as do “Talk” and the first of two poems entitled “Brooklyn Interior.” The longish “Letter to Doc,” the strongest poem in the book, invokes a complex of emotions that it tries but luckily fails to subsume as “love”:

From here I can see

the rain-slicked streets,

the points where they meet,the florescence of gold, red, & green—

the variant shadows

where I have kept you:around corners, in bars,

in sudden light that blisters

into flurries of snow.

More exploratory and adventurous than most of her poems, this one follows itself to a teasingly honest conclusion. She will surely write more like this.

Jeffrey Schultz [5], on the other hand, is nothing if not adventurous. His taste for rugged metaphor and jagged little narratives enlivens poems that otherwise, given their subjects, could have wallowed in the quotidian: “Summer’s blast furnace could peel the skin / right back from your face,” one poem begins, while another invokes a familiar contemporary urban drama: “Police helicopters searchlights suddenly useless, / dawn-break dispenses its smog-tinged grace on the pursued.” His titles are often intriguing: “J. Steals from the Rich and Uses the Money to Get Drunk Again,” and “The Velvet Underground’s ‘Sweet Jane,’ from Two Minutes, Thirty-Three Seconds to Two Minutes Fifty-One Seconds.” Schultz’s lines tend to length, and generally hold themselves to their rhythms. Sometimes the effect becomes too rich, like an elaborately decorated cake. But Schultz writes with energy, and if he sometimes overwrites, freighting his material with more verbal force than it can bear, this is a chance a real poet takes.

Jeffrey Schultz [5], on the other hand, is nothing if not adventurous. His taste for rugged metaphor and jagged little narratives enlivens poems that otherwise, given their subjects, could have wallowed in the quotidian: “Summer’s blast furnace could peel the skin / right back from your face,” one poem begins, while another invokes a familiar contemporary urban drama: “Police helicopters searchlights suddenly useless, / dawn-break dispenses its smog-tinged grace on the pursued.” His titles are often intriguing: “J. Steals from the Rich and Uses the Money to Get Drunk Again,” and “The Velvet Underground’s ‘Sweet Jane,’ from Two Minutes, Thirty-Three Seconds to Two Minutes Fifty-One Seconds.” Schultz’s lines tend to length, and generally hold themselves to their rhythms. Sometimes the effect becomes too rich, like an elaborately decorated cake. But Schultz writes with energy, and if he sometimes overwrites, freighting his material with more verbal force than it can bear, this is a chance a real poet takes.

Another hazardous undertaking is to invoke the Freudian world of folk and fairy tales. Laden with baggage from years of study by literary anthropologists like Vladimir Propp and psychologists like Bruno Bettelheim, this genre seemed overdetermined from the start. Sarah Rose Nordgren [6] invokes it gently by devising delicate or fragile female figures who come to no great harm but experience the intricacies of their own being in sometimes trancelike states:

Another hazardous undertaking is to invoke the Freudian world of folk and fairy tales. Laden with baggage from years of study by literary anthropologists like Vladimir Propp and psychologists like Bruno Bettelheim, this genre seemed overdetermined from the start. Sarah Rose Nordgren [6] invokes it gently by devising delicate or fragile female figures who come to no great harm but experience the intricacies of their own being in sometimes trancelike states:

Surely she’s worth seven years,

the black girl who hangsin the corner like a dress,

insisting on silencewith her rosebud eyes, I drink

from the family cupsolemnly while she dances

a ghost dance with herself.

(“Instructions for Marriage by Service”)

Such poetry can be highly effective in creating subtle emotional moods. The trick is to let the poem evolve to a climax and closure without betraying that mood, and Nordgren is good at this. Her poems aren’t dramatic enough to call a great deal of attention to themselves, but their subtleties are worth exploring.

Drama, however, may inhere not so much in the individual poem but in the arrangement of the entire collection. Henry Walters [7] has structured his first book in “movements.” Most of these movements consists of three parts: a freely associative prose poem, a sonnet, and a more loosely assembled verse poem. The central eponymous section presents a series of poems about the textures and anatomies of physical being:

Drama, however, may inhere not so much in the individual poem but in the arrangement of the entire collection. Henry Walters [7] has structured his first book in “movements.” Most of these movements consists of three parts: a freely associative prose poem, a sonnet, and a more loosely assembled verse poem. The central eponymous section presents a series of poems about the textures and anatomies of physical being:

Doctoring stones takes hands, no chisel, no blade,

Pressure-tuned & -tendoned, palms & callouses

Calibrate as fine as a set of scales.

Deal gently. Pound & be kind . . . .

A classicist and naturalist, Walters relies heavily on allusion, some of it obscure, and his work suggests a thorough grounding in Ezra Pound’s aesthetic (the “Pound” in the above quotation may be a clue). The book is constructed so effectively that it is difficult to consider its parts separately from the whole. But the individual poems—whether the prose poems, sonnets, or the free verse poems—are generally effective, and a few, like “Medieval Memory Place,” “Of the Relative Motion of Bodies,” and “Rondo alla Turca” are remarkable for their linguistic and semantic daring. For Walters, identity is a larger construction that inheres in the fine grain of the natural world and the long history of human culture (especially music), and his work is inextricable from it.

The prose poem dominates Siobhán Scarry’s [8] first collection. Her aggressive wielding of language, crashing words and images together sometimes with nuclear force, suggests that she’s too impatient for verse. Her relatively few verse poems are quieter, less forceful but still cunning in their shaping of imagery. The one sentence-poem “Dream of the Moving Image” demonstrates that she can be adroit with the line, but the sheer exhilaration of language in poems like “After Blackdamp” shows why she prefers the hybrid form:

The prose poem dominates Siobhán Scarry’s [8] first collection. Her aggressive wielding of language, crashing words and images together sometimes with nuclear force, suggests that she’s too impatient for verse. Her relatively few verse poems are quieter, less forceful but still cunning in their shaping of imagery. The one sentence-poem “Dream of the Moving Image” demonstrates that she can be adroit with the line, but the sheer exhilaration of language in poems like “After Blackdamp” shows why she prefers the hybrid form:

Floating free across the fences that separate the empires of our backyards, each particle of dust alive and lit with summer. Feet skittering in shale slide, moccasins stuttering on the shallow creek water, and the children’s children of the Pennsylvania miners caper in aboveground air, white flesh of their feet bloaty and wavering under the blurry microscope of free time.

This passage also shows her tendency to over-alliterate, and to rely on the associative sound of words. The primary impulse of the book is the play of mind and language in the act of image-making, so Scarry is drawn to ekphrastics and other representations of the visual. Her poems are less predictable and more aleatory than those of poets with more social or psychological concerns, and more fun to read.

Even more aggressive in their wrestling with language, Cody-Rose Clevidence’s [9] poems, according to an equally aggressive blurb, “descend into an underworld of decaying, regeneration language, whose prophetic argument about the natural world augurs etymologies of corroded animalia and a bibliomancy of theriophagic power.” This combination of bad grammar and pretentious terminology sometimes afflicts the poems as well, but Clevidence provides a catalogue of contemporary experiments that is unrivaled in a single volume in this reviewer’s experience. A sample that illustrates the thematic leaps hinted at by the above blurb:

Even more aggressive in their wrestling with language, Cody-Rose Clevidence’s [9] poems, according to an equally aggressive blurb, “descend into an underworld of decaying, regeneration language, whose prophetic argument about the natural world augurs etymologies of corroded animalia and a bibliomancy of theriophagic power.” This combination of bad grammar and pretentious terminology sometimes afflicts the poems as well, but Clevidence provides a catalogue of contemporary experiments that is unrivaled in a single volume in this reviewer’s experience. A sample that illustrates the thematic leaps hinted at by the above blurb:

IN TUCSON ALL THE ORANGE TREES

ARE ONLY ORNAMENTAL. TEARS

CONTAIN MANGANESE. IAMBIC

PENTAMETER IS AN ARTIFICIAL

STRUCTURE THAT RISES OUT OF

LATINATE INTONATION LIKE HOW

MATH RISES OUT OF THE INTER-

ACTIONS OF MATTER.

Ignoring the clumsy interpolation of “like how” for “as” and the billboard of capitalization, it is obvious that Clevidence writes with verve and intelligence, forcing together disparate images and ideas in a manner that could be productive. Her book offers many vividly written and challenging passages, and a few entirely convincing poems. Whether the reader is prepared to sweat through many pages of not-so-warmed-over post-Language poetry excess (much of the section entitled “This is the Forest”) is a matter of personal preference, but nearly every page of this sometimes enraging book has at least a phrase, an image, or a whole passage of animated writing worth reading. While her experimental gymnastics—some drawn from the concrete poets of the 1960s—aren’t original or particularly exciting, the underlying voice has something to offer.

In a quieter and more orderly way, Jay Nebel’s [10] poems also associate incongruent images in an effective manner: “Every day I’m more like a beached / whale waiting for someone / to pull out his fishing knife and open me up” (“Lawns”). His lyrics are relentlessly suburban and domestic, but with violent or tragic overtones, and bursting with frustrated energy: “All this food should make me want / to shove my face through the television / and root around, drunk / on shortcake and apple pie” (“The Food Network”). Lively verbs propel his speaker in a flash from innocent perception to sometimes grotesquely harsh imagery. He manages to describe the elderly Jack Gilbert as “a crumbling masterpiece / from the Renaissance” (“Montage with Pittsburgh, Jack Gilbert and My Korean-Born Son”). How can one not admire these poems? Revenge and schadenfreude darken them to good effect: “I feel better knowing / that my friend who seared my eyebrow / weighs over four hundred pounds” (“Paradise”). Some of the poems meander a bit, and occasionally the grammar lapses, but this collection is a thoroughly good read.

In a quieter and more orderly way, Jay Nebel’s [10] poems also associate incongruent images in an effective manner: “Every day I’m more like a beached / whale waiting for someone / to pull out his fishing knife and open me up” (“Lawns”). His lyrics are relentlessly suburban and domestic, but with violent or tragic overtones, and bursting with frustrated energy: “All this food should make me want / to shove my face through the television / and root around, drunk / on shortcake and apple pie” (“The Food Network”). Lively verbs propel his speaker in a flash from innocent perception to sometimes grotesquely harsh imagery. He manages to describe the elderly Jack Gilbert as “a crumbling masterpiece / from the Renaissance” (“Montage with Pittsburgh, Jack Gilbert and My Korean-Born Son”). How can one not admire these poems? Revenge and schadenfreude darken them to good effect: “I feel better knowing / that my friend who seared my eyebrow / weighs over four hundred pounds” (“Paradise”). Some of the poems meander a bit, and occasionally the grammar lapses, but this collection is a thoroughly good read.

Autobiography still dominates the contemporary lyric, but it doesn’t have to embrace the identity mode. Nancy Reddy [11] filters hers through second-person and third-person poems as well as the more familiar first-person narratives. Their aura of self-witness, of the relentless presence of the speaker, gives them away. She writes with a great deal of pathos enlivened by humor, as in “Paper Anniversary”: “The happy couple’s in the kitchen / so I’m in the side yard doing my best imitation / of a doghouse.” Also energized by vividly focused imagery, these poems at their most effective transcend the imperatives of the self and open into a larger but still immediate world:

Autobiography still dominates the contemporary lyric, but it doesn’t have to embrace the identity mode. Nancy Reddy [11] filters hers through second-person and third-person poems as well as the more familiar first-person narratives. Their aura of self-witness, of the relentless presence of the speaker, gives them away. She writes with a great deal of pathos enlivened by humor, as in “Paper Anniversary”: “The happy couple’s in the kitchen / so I’m in the side yard doing my best imitation / of a doghouse.” Also energized by vividly focused imagery, these poems at their most effective transcend the imperatives of the self and open into a larger but still immediate world:

When we were children we wanted to be orphans.

The snow came early and halved the treeline.

Branches still flush with leaves heaved with ice and snow

and split at the waist.

(“Games”)

Reddy writes some predictable poems about the psychological oppression of women by badly chosen men, but even then she shapes her work gracefully and fuels it with vivid tropes. While poems like “Come Fetch” and “All Good Girls Deserve” run the risk of distancing some readers, as this review mentions above, Reddy maintains her poise and avoids the self-pity that might cause an impatient reader to close the book.

Moving away from autobiography to a more objective mode, Adam Day’s [12] work, shadowed with social and political violence, suggests the Auden of the 1930s, as in “A Police History”:

Moving away from autobiography to a more objective mode, Adam Day’s [12] work, shadowed with social and political violence, suggests the Auden of the 1930s, as in “A Police History”:

Walking through ice-seamed streets

to a theater, a streetcar full of talking

bodies passed a woman, before a column

of tanks rolling towards the town square

to confront a revolt.

The first person, less ubiquitous than in most of the other books reviewed here, is usually an obvious persona: “I was a woman before the war— / we took the arms of our enemies // and swung them from our crotches” (“Before the War”). The atmosphere is thick with foreboding. Even poems that seem to be about the poet himself, like “Time Away,” seem fraught with cruelties shortly to be enacted. The world of these poems both is and isn’t ours; Day offers a cautionary look at where the world is going, and how it is dragging us with it. So much of it seems eerily familiar, yet still unrealized. In his odd way he speaks for many of us, for our darker awareness: “I’m not wary of myself, or others, / but myself in the presence / of others. It might be safest / to say home and read” (“Now and Forever”). As he says, as we all might say, “It took me a long time / to become a human being” (“He Speaks of Old Age”). The specter of war looms over this collection. It’s the war Auden experienced in the 1930s: the ghost of a war that hasn’t yet occurred, but which is surely coming. A creepy and compelling book.

Also a bit creepy and persuasive in its invocation of violence as the quotidian, Jynne Dilling Martin’s [13] collection wields long not-quite-Whitmanesque lines to good advantage:

Also a bit creepy and persuasive in its invocation of violence as the quotidian, Jynne Dilling Martin’s [13] collection wields long not-quite-Whitmanesque lines to good advantage:

The hunter pushes a bullet beneath his tongue to fix his aim,

or is it to stave off thirst? The antelope pausing at the brookfears each snap. The child drinks, the child is tired, for the child

the day is done. Some animals enter caves and never reemerge . . . .(“A Spell for going Safely Forth by Day”)

Her inventive imagination, however, salts this foreboding world with vivid details, colors, and textures: “The night I am captured, tortured, and biting a stick, / to taste its hard green tang” (“Resolutions”). The strangeness of her poetry is that of a relentless imagination that almost occludes everyday actuality and defies any distinction between the inner world of the poet and the world outside of her mind. What can the reviewer say about a poem entitled “Autopsies Were Made with the Following Results” and opens with, “I draw uncounted fugues from pianos but no consolation, / and recall the ogre who mistook hot coals for roasted nuts”? What world does she live in that allows her to write “Like an adopted cat, your planet hates its name” (“Revelations”)? Martin knows something the rest of us don’t.

Instead of aggressively dynamic language, a degree of cool objectivity helps empower Kerry-Lee Powell’s [14] poems. She handles simple and straightforward description with a measured cadence and confident diction:

Instead of aggressively dynamic language, a degree of cool objectivity helps empower Kerry-Lee Powell’s [14] poems. She handles simple and straightforward description with a measured cadence and confident diction:

An old man on a folding lawn chair,

his bald head and freckled hands

reflected in the ornamental pondwith its tadpoles and its muck

and the whirring of the pump

he has spent all day trying to fix.

(“The Encounter”)

Her work draws in the reader with the anecdotal verve of good short stories (she is also an accomplished fiction writer), and transfixes with exacting imagery that surprises not for its imaginative leaps but for its grim precision:

You knew the fires in the vacant lots

might turn you to ashes, but you heaped

the chairs you took from the church hall

watched the smoke twist into hooks

and wondered, who would be king?

Possibly because she’s Canadian, and detached from the aesthetic tensions of the American MFA world, her poetry shows none of the inclinations toward sentimentality, identity angst, or experimental urgency that afflict those of us below the forty-ninth parallel. It’s unfortunate that a large blurb on the back cover of her book praises her “dark nostalgia,” since that unbecoming emotion is infrequent in her work.

These fourteen new poets all transcend, to some degree, the limitations of poetry in our time. Those limitations are more social than aesthetic and help determine who gets published, which voices we’re allowed to hear, and where we can find them. The difficulty of truly making it new—writing poetry that discovers all over again the original freshness of the language—is exacerbated by the oversupply of poetry in bookstores, on the internet, in the classroom. Frost reminds us how vital is the sense of discovery in writing poetry—“no surprise for the poet, no surprise for the reader”—but with the institutionalization of poetry, surprise is a rare commodity. Yet each of these poets has at least a bit of surprise for us; in some instances more than a bit. As long as poetry remains a vital art—as long as language is important to us—that attempt to recover an original freshness will persist, and occasionally prevail.

[1] David Campos, Furious Dusk. Notre Dame: Notre Dame University Press, 2015. ISBN 978-0-268-02377-5. $17.00, paper. Return to Text

[2] Susannah Nevison, Teratology. NY: Persea Books, 2015. ISBN 978-0-89255-458-4. Return to Text

[3] Sean Bishop, The Night We’re Not Sleeping In. Louisville: Sarabande Books, 2014. ISBN 978-1-936747-93-1. $14.95, paper. Return to Text

[4] Cathy Linh Che, Split. Farmington: Alice James Books, 2014. $15.95, paper. Return to Text

[5] Jeffrey Schultz, What Ridiculous Things We Could Ask of Each Other. Athens: University Press of Georgia, 2014. ISBN 978-0-8203-4721-9. $16.95, paper. Return to Text

[6] Sarah Rose Nordgren, Best Bones. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2014. ISBN 978-0-8229-6317-2. $15.95, paper. Return to Text

[7] Henry Walters, Field Guide A Tempo. Brookline (NH): Hobblebush Books, 2014. ISBN 978-1-939449-06-1. $18.00, paper. Return to Text

[8] Siobhán Scarry, Pilgrimly. Anderson (SC): Parlor Press, 2014. ISBN 978-1-60235-481-4. No price given. Return to Text

[9] Cody-Rose Clevidence, Beast-Feast. Boise: Ahsahta Press, 2014. ISBN 978-934103-53-1. $18.00, paper. Return to Text

[10] Jay Nebel, Neighbors. Ardmore (PA): Saturnalia Books, 2014. ISBN 978-0-9915454-6-9. No price given. Return to Text

[11] Nancy Reddy, Double Jinx. Minneapolis: Milkweed Editions, 2015. ISBN 978-1-57131-477-2. $16.00, paper. Return to Text

[12] Adam Day, Model of a City in Civil War. Louisville: Sarabande Books, 2015. ISBN 978-1-941411-02-5. $14.95, paper. Return to Text

[13] Jynne Dilling Martin, We Mammals in Hospitable Times. Pittsburgh: Carnegie-Mellon University Press, 2015. ISBN 978-0-88748-596-1. $15.95, paper. Return to Text

[14] Kerry-Lee Powell, Inheritance. Windsor, Ontario: Biblioasis, 2014. ISBN 978-1-927428-79-5. $16.95, paper. Return to Text

Published on September 25, 2015