Brooklyn

by Virginia Marshall

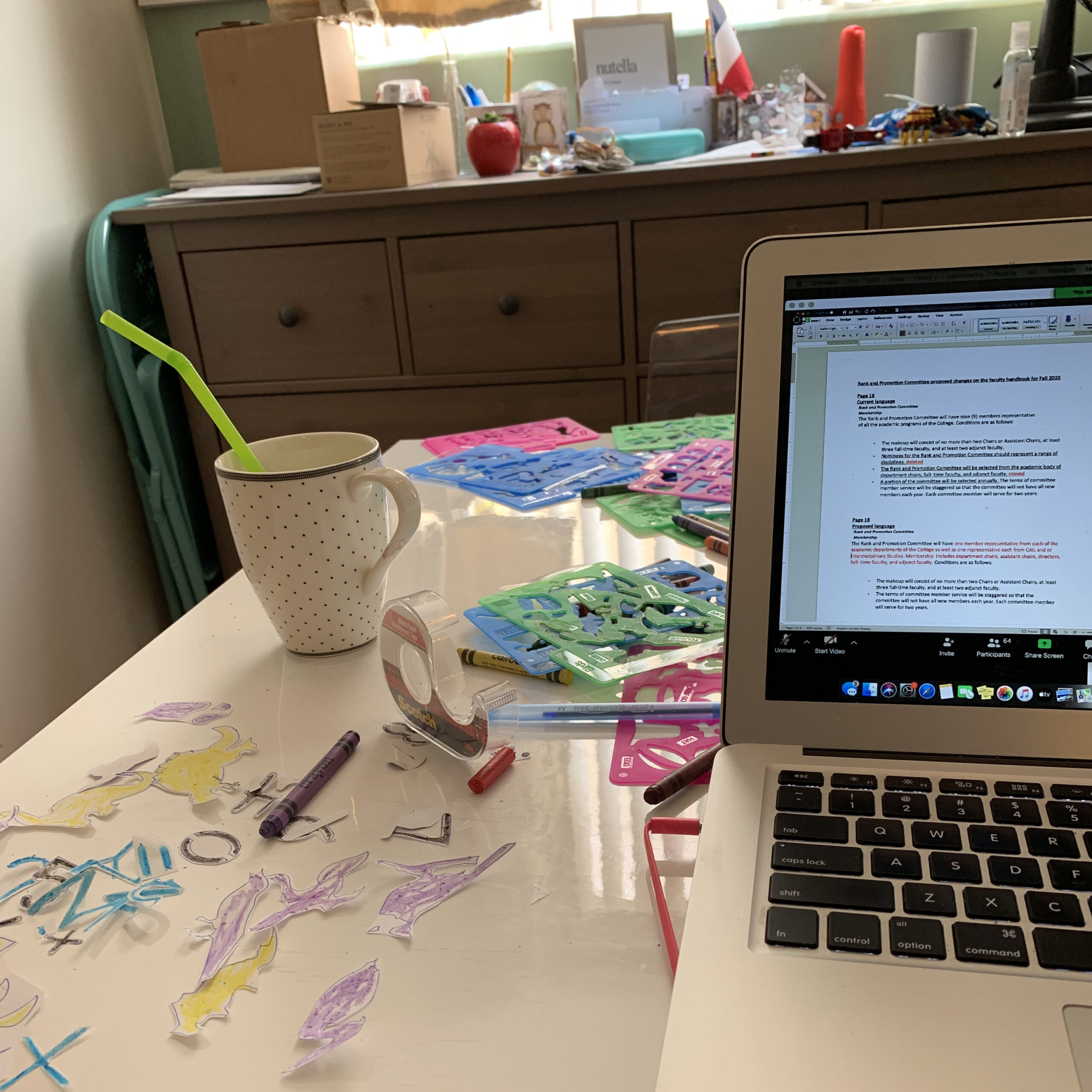

I have decided to read poetry on my stoop. I do it every day, after signaling the end of my work day by posting a waving-hand emoji to my team’s Slack group. I still have my copy of The Norton Anthology of Poetry from college, though its edges are now chewed, and, because he’s right smack in the middle of the book, I’ve decided to start with Keats. In college, I memorized a Keats poem about dying young. It moved me greatly at eighteen, but now I just like the sounds. So, I read aloud, ignoring the passing people and their dogs.

In the middle of the second sonnet, I hear David the mailman leave Zona’s house. Zona is my next-door neighbor and David is her boyfriend.

“If you go to BJ’s,” she is saying, “pick up a case of water.”

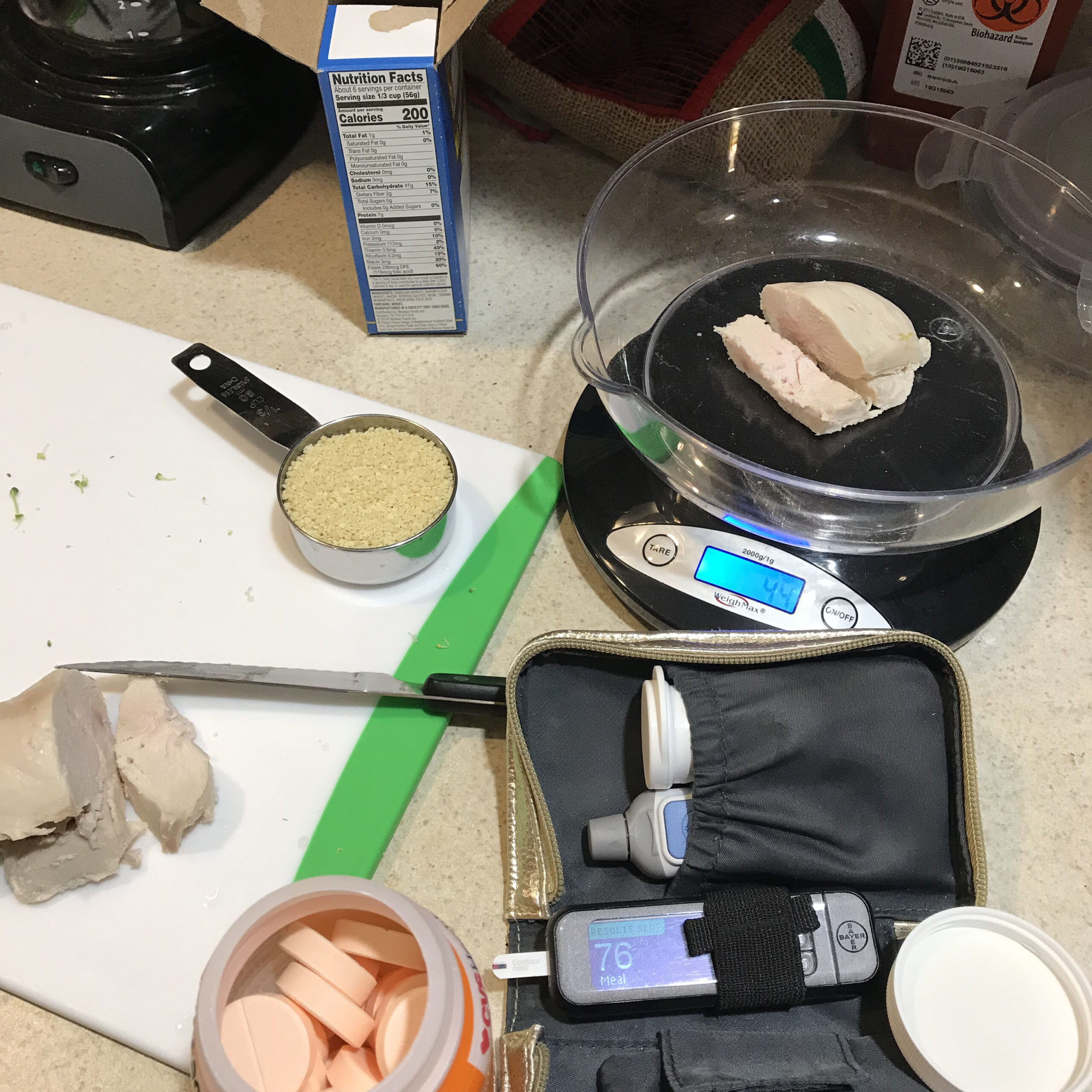

David waves, pushing his cart of letters ahead of him. Zona stands on her stoop a moment longer and we chat about fried plantains (her) and sourdough starters (me) and I have to shield my face from the sun to see her.

“This thing is going to peak in two weeks and then it’ll go away.” My dad sounds like he’s talking about a heat wave.

“Dad’s an optimist,” says Mom.

“Can I finish my thought?” Dad again. I keep quiet and pick at the threads on the end of my rug.

“Do you need money?” Mom says.

“No,” I say, embarrassed.

She and my dad counter each other: the pessimist and the optimist. Both of them spend their days quelling their patients’ anxieties, donning masks, taking temperatures, stripping down when they get back to their Manhattan apartment: clothes straight in the wash, bodies in the shower. I resist the urge to call them more than three times a week because I know my mom hates talking on the phone. And anyway, they spend their whole days talking patients off the ledge, so to speak. No need to add to their work.

“But be safe,” I say, during a pause in their banter.

“We’re fine,” says Mom.

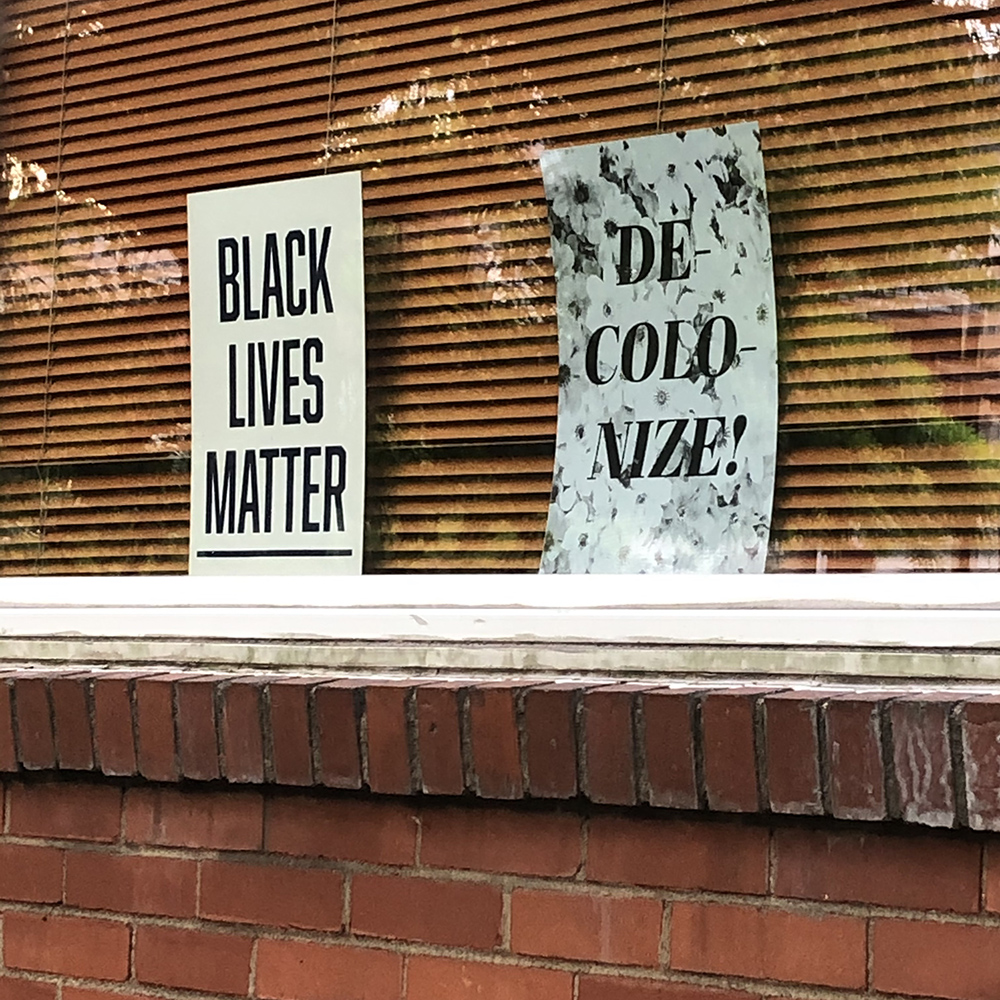

Later, in my bedroom, after Keats and the stoop, I hear shouting from outside. I remove the screen from my window so I can see down the block. A middle-aged white woman is yelling at a car. My housemate has heard the yelling too, and she stands frozen, one leg lifted over the seat of her bicycle. She is an essential worker, off to her shift at the grocery store.

“Wait,” I call to her, hanging out the window and feeling like a woman in an old film. I should be flapping a rug against the side of our brownstone or pouring gray water out the window. But instead I am pointing and narrating a scene that my housemate, two floors below, cannot see.

“Someone is hitting a car with a golf club,” I say, not at all sure that my voice carries far enough to be useful. “The car is driving away. They’re yelling at it. Now there’s a man with a baseball bat.”

My housemate is looking at me, her eyes wide above her hand-sewn mask. We are frozen until the shouting stops. Then the people go inside.

“Okay,” I say. “Be safe.”

My housemate bikes away and I sit down on the floor and listen to the sirens arriving too late. I reach for my phone and almost call my parents, but I don’t. They are fine and I am fine. I am indoors.

Published on April 23, 2020