Contributor Bio

Ruben Quesada

More Online by Ruben Quesada

Archaeologists of the Elusive: Six Books by Latinx Poets

by Ruben Quesada

This summer, while writing a lecture on queer joy and poetry for a Tin House Summer Workshop, I traced my personal connections to queer Latinx poets of the late twentieth century. After reading these six 2022 releases by Latinx poets, I see how my poetic predecessors are theirs, too.

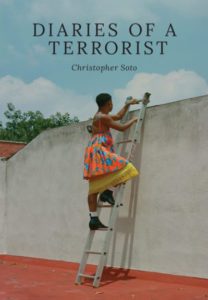

For example, the first poetry class I ever took was at East Los Angeles College; twenty years earlier, the poet Francisco X. Alarcón had studied poetry at East LA College. Since his first chapbook in 1985, Alarcón wrote in Spanish and English, back and forth, code-switching. In his 2016 Los Angeles Times obituary, Alarcón’s poetry is described as having “a leftist political flavor,” written with “pro-immigrant activism” and containing “themes of outsider identity.” He wrote about living as “a gay Latino man raised in a pious Catholic family” and “remained closeted into late adulthood.” Today, Alarcón’s play with language and attention to the fate of the outsider finds echoes in the forthright criticisms of Christopher Soto’s Diaries of a Terrorist, or in the linguistically and formally metamorphosing poems of Paul Hlava Ceballos’s banana [ ].

The poetry of Gil Cuadros, like that of Francisco X. Alarcón, also speaks to me. I grew up in Los Angeles, and when I came out, West Hollywood was the only place where gay people could be themselves in public, yet I rarely saw people of color there then. In “My Aztlan: White Palace,” from his 1994 debut collection—and his only published collection—Cuadros’s speaker narrates a drive home from gay bars in West Hollywood, where, we learn, he faced the “disappointed” reactions of white gay men when he told them where he was from. His childhood home was cleared to construct the freeway his car travels over, and he imagines “the house still intact, buried under dirt and asphalt.” Invoking the legendary long-lost homeland of the Aztec people, he adds: “this is my Aztlan.” Cuadros’s writing is a testimony about the queer body, the AIDS crisis, and what it means to belong. Such attention to the present-day effect of violent, imperialist histories takes a new form in Jasminne Mendez’s City Without Altar; meanwhile, Cuadros’s treatment of illness and personal legacies has kinship with Alexandra Lytton Regalado’s tender and resilient Relinquenda.

At this time of year, I have more than one hundred books of new poetry on my shelf, and dozens more will have arrived by the time you read this. Every year, large and small presses publish more poetry collections by Latinx poets. Most years, I know which books I want to write about by mid-year, but this year was tough. Though I can’t write, or even know, about every new collection published by a Latinx poet, I am grateful for this abundance and the connections it creates.

FlowerSong Press

Ariel Francisco’s third collection, Under Capitalism If Your Head Aches They Just Yank Off Your Head, is filled with portraits of real and imagined moments. Each poem includes, on the facing page, a Spanish-language translation by José Nicolás Cabrera-Schneider. The poems are disarming in their simplicity and plain style.

In “For My Uncle Kiko, Who’s Spent Most of His Life in Psychiatric Hospitals With Schizophrenia,” a visit to a loved one turns into a picture of social control. The speaker relinquishes his phone, a fact that expands the schism between Uncle Kiko and his visitors: “the armed security says its to / protect the patients,” even if “it’s a real shame we can’t / take pictures with our loved ones.” The devastating image of Kiko, a man “bent almost in half” with a “toothless mouth,” shows how healthcare for the mentally ill is often discordant with humanity.

The poem “According to My Birth Certificate, My Mom Is From ‘Guatemala, California,’” describing a moment of erasure by the supremacy of “the US ego,” is both jocose and discerning.

She wrote down CA for Central America

but the US ego sees what it wants,

unintentionally granting her citizenship

[ … ]

Yes, my mom is from a place that does not exist.

Charles Baxter once described listening to Larry Levis as an overwhelming experience, characterizing Levis’s poems as built from “an elaborate-but-austere syntax, the phrases and word-choices almost painfully fastidious, the evidence of great care taken with every feature of the poem, creating an indelible impression.” I find this in Francisco’s poems, with their careful and striking lines: “Moonlight humiliates the landscape: / in the empty stadium a fascist throws / the first pitch. There are no cheers.”

•

Noemi Press

Jasminne Mendez’s debut poetry collection City Without Altar is a hybrid work that blurs the past and present, text and image to craft a portrait of the speaker’s inheritances, near and far. The opening poem, “Inheritance,” frames a partially redacted image of the Black and Dominican-American poet’s Alabama birth certificate with the question “What will they make us forget?” and a critique of the racial erasure the document enacts by naming her only as “Hispanic”: “On this day in history. I am born. Alive. Let the record show. I am. Hispanic. Not Black. This is legal. A record. Permanent. All items listed are accurate. And complete. On this day in history. I am. Blacked-out.”

Mendez uses images—maps, photographs, and blackout poems—to corroborate, then expand her commentary and poetic reflections. The most memorable section and centerpiece of the collection is a two-act play with production and dramaturgical notes, a historical reimagining of the lives of seven people affected by the Parsley Massacre, a mass genocide of Haitians on the Dominican Republic’s northwestern frontier in 1937. An estimated twenty thousand Haitians were killed in the massacre, ordered by dictator Rafael Trujillo.

Between scenes are “Interludes,” with high-contrast X-ray and ultrasound images representing the poet’s experience with scleroderma, a condition that brings the hardening of the skin and often leads to amputation. Under each image is a prose poem about hands. The interludes add a multi-layered point of view—the interiority and exteriority of the poet are present on the page, literally and metaphorically.

One single cross-stitch scar stretched across the bone. The would be no more wash, rinse, wrap, and repeat. There would be no more infection or gangrene. There would be no more fingertip, fingerprint, or nail. Just this—a phantom pain pulsing—the final remedy.

•

University of Pittsburgh Press

Paul Hlava Ceballos’s banana [ ] is a tender and magical collection split into three parts: “Elegies,” “A History of America,” and “Irma.” The first half of Part One comprises elegies for people murdered by US Customs and Border Patrol agents, and the second half is a series of persona poems voiced by rulers of the Incan Empire, before and after the Spanish Conquest. After the Inca Civil War (1529–1532), the Spanish chose and installed an Inca leader, who speaks in “Túpac Huallpa, the Puppet King”:

I proclaim the invaders gods

with a slipknot lodged in my throat.

Who are these men on hooves who claim

stones pulled from our earth, and our earth?

Part Two is a long, epic poem written as a collage of unique texts that contain the word “banana.” The sources for these lines include government documents, interviews, testimonies of the labor force, news articles, and more. Their notes direct readers to the poet’s website to trace almost three hundred sources:

one banana169

of banana170

many banana171

but banana172

small banana173

For the five lines above, the website provides citations of articles about child labor, agrarian reform, and chemical poisoning in the banana trade. I admire the engagement this form encourages; it successfully uses the digital space to create an ecosystem of knowledge.

The third and final part of banana [ ] remembers the speaker’s mother. In “Irma,” a black-and-white photograph of a woman posing on the floor, wearing a business suit, is placed beside text:

The lie my mother told me

took decades to see. See?I stand under

a flowering apple tree’s shade.

Follow?

With this question—Do you follow? Will you follow?—the speaker asks us to take a journey with him. This long poem is mesmerizing, moving from formal structures like quatrains and tercets to more text and photo pairings and flowing from English to Spanish seamlessly.

•

Beacon Press

The debut collection Relinquenda by Alexandra Lytton Regalado was selected for the National Poetry Series in 2022. This collection takes its title from the Latin word relinquendus, for which a definition is provided at the start of the collection: “which is to be abandoned, which to be relinquished.” The poems are intimate yet constraining, closely mapping personal experience and drawing a reader into what Sven Birkerts calls “the gravitational space of the work.”

“Portrait of My Father X Days Before Dying” is a particular standout, cascading across two pages in prose. The speaker recalls seeing her father alive for the last time, backlit by the sun as he smokes on the terrace: “He leaned forward & let out a fine stream of drool, & there was terror & beauty, all perfectly illuminated in his silhouette. I have to describe it in detail, though no one will want to read this, my mother assures.”

There is a tenderness in describing this drool as “fine.” The father is all spit and gums in these last days of life before he dies of throat cancer, but in remarkable contrast, his “perfectly illuminated” silhouette calls to mind a romantic figure. The poet’s grief brings uncertainty and new attention to impermanence: “that was your language, the things you were certain of, that you could prove, & for me those computations were spiderwebs, tangled & shredded by wind.”

Near the end of the collection, with “What My Father Taught Me About Time Travel,” Regalado is delicate and forthright:

I want to need to repeat you again

& you need to leave

so emptied you cannot fill

the bowl-headed sky, the antiseptic clouds

burning white.

These poems, written by a daughter about a father, may make readers think back to Sylvia Plath’s “Daddy” and Anne Sexton’s “All My Pretty Ones.” Still, they are much closer to Robert Hayden’s “Those Winter Sundays”—resilient, introspective, and reverent.

•

Four Way Books

Yesenia Montilla is an Afro-Latina poet and a daughter of immigrants from the Dominican Republic and Cuba whose second collection of poetry, Muse Found in a Colonized Body, evokes the past to consider how colonialism continues today. The book begins by looking back:

They say when the Spaniards came we thought then

gods. They came with sincere eyes, but insincere

mouths & cocks they knew something about the

universe & we only knew about the earth

The title poem of this thought-provoking collection returns multiple times to introduce its eleven sections, with the aim of setting the foundation for each section about labor, class, stigma, activism, love, and more. A powerful poem in the third section is “To Pimp a Butterfly as Muse,” a critique of having a “white boy stage” and the silence of unsustained activism:

Dissent these days is so hushed voiceless even

You could hear a Black Lives Matter button plummet

Into the abyss never to be imagined again—

The fifth section introduces poems about wealth and capitalism: “We ruin everything. & / we still beg for beauty.” It includes poems like “Hamilton Heights Starbucks” and “La Bodega—A Gentrification Story.”

At its end, the collection arrives at our contemporary moment, and then the final poem, “Muse Found in Magical Realism,” leaps forward into a mythic future, with echoes of the Metamorphoses:

Towards the end, she took off the gloves

to feel the world & it turned into a pile of

clovers. Having lost everything she touched

her own body & became cattle

she ate the world ate it all—

•

Copper Canyon Press

In Diaries of a Terrorist, Christopher Soto examines language and explores the abolitionist possibilities of poetry. The book’s epigraph—“Not a man, but a cloud in trousers”—is a famed line from Vladimir Mayakovsky, a Russian Futurist whose work criticized capitalist institutions. Similarly, in this collection, Soto takes aim at state violence, in both its cultural and physical manifestations.

The poem “The Terrorist Shaved His Beard” considers the etymology of the word “terrorism” and xenophobic uses of the word:

[ … ] maybe // The root of terrorism is error

Etymologically derived from

The Greek // Err // Meaning to be incorrectOr maybe we err in the etymology

Maybe we’re wrong // To think terrorism means

One who exists incorrectly on this land

The memorial poem “Meteor Shower // Or Where the Sky Skid Its Knees,” feels like a twisted techno-thriller as it describes the police state with action and scene:

Police killed our neighbor // On his

Doormat // Fifty footsteps from his bed [ … ]After the first shot // We fell to the floor & then fell

Into the basement // Where the computer couldn’t speak up

Huddled in the corner // Downloading the latest version of him

The polyvocal speaker contemplates their own safety in the final line: “Who’ll protect us // From police // If not ourselves.”

As poets and writers, we bear witness to the world—and most importantly, to the ordinary, the overlooked, and the disenfranchised. Poems serve as a record of a life lived, even if that record may seem inscrutable, ambiguous, or imagined. In his foreword to an anthology I edited, Latinx Poetics: Essays on the Art of Poetry, the former US Poet Laureate Juan Felipe Herrera describes writers as “warrior-seekers, philosophers—survivors, archaeologists of the elusive and ungraspable self.” Each act of writing is an utterance of the elusive; there is never a singular way to create or understand poetry. These six collections offer six unique, artful testimonies of an elusive and ungraspable world.

Published on December 14, 2022