Contributor Bio

Alice Hoffman and Christina Thompson

More Online by Alice Hoffman, Christina Thompson

An Interview with Alice Hoffman

by Christina Thompson

In this conversation with editor Christina Thompson, award-winning novelist Alice Hoffman reflects on her writing and looks back at three stories she published in the early 2000s in Harvard Review.

Christina Thompson: I wanted to start by asking you how many books you have written.

Alice Hoffman: I don’t really know, but a lot. I’m not sure how many. I haven’t kept track. I think about thirty.

CT: One of my favorite Harvard Review contributor notes was John Updike’s. It said something like “John Updike is the author of over fifty books.”

AH: I have this impression—it’s probably wrong—that it came easily to him because his prose is so fluid. I have the sense that he just sat down and then there it was. But, you know, there are people who think that about me. It’s probably never true of anybody, but it seemed like it was true of him.

CT: It probably isn’t ever true of anybody. I tend to think that the people who get a lot done are the people who work hard.

AH: That’s my take, too. I mean, I work all the time. It’s probably not the best thing to do, but that’s what I do.

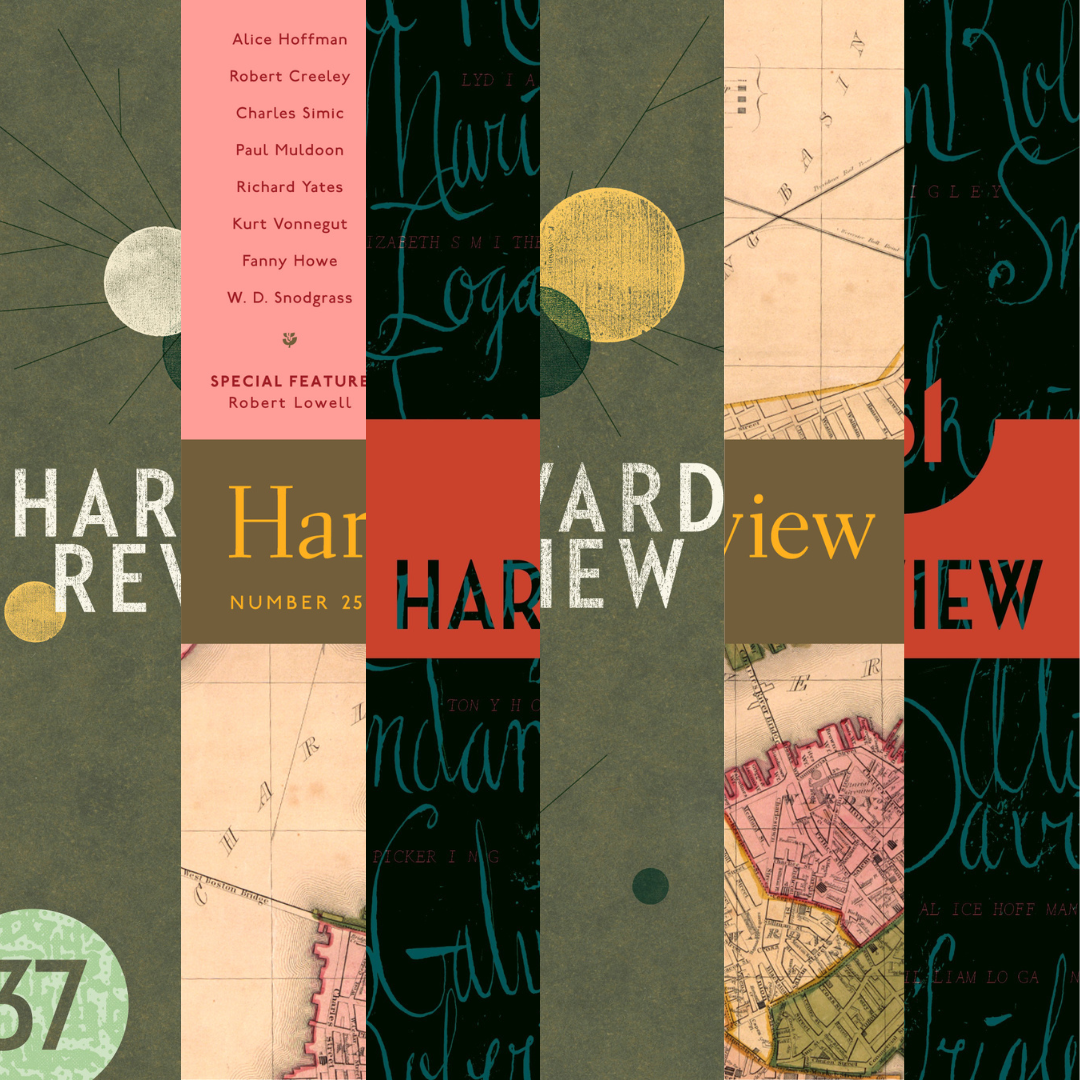

••• Read Alice Hoffman’s “Lionheart,” published in Harvard Review 25 •••

CT: We published three stories of yours in the aughts, and I think we should take them in chronological order beginning with “Lionheart.”

AH: This story is an extract from a book of linked short stories (my favorite thing to write and my favorite thing to read but not necessarily publishers’ favorite thing to publish). It was from Blackbird House (Doubleday, 2004), and all the stories took place in the same house, on a farm that I used to live on a long time ago. I loved that house so much and I just kind of imagined what the history of the house might have been.

CT: This story, which starts in 1908 and involves one of several families who appear in the book, is really kind of heartbreaking.

AH: Yes, because it’s about your love for your children and how you can’t really protect them, no matter what. The mother has several children, but one of them is the child she loves beyond measure, and she wants him to have a different life. They’re farmers, you know, the kind of people who live on a run-down farm with no heat.

CT: We don’t learn until fairly far into the story that this child has a different father from the others. I didn’t see that coming, but as soon as I learned it, it was like, Oh, of course he does. That wasn’t the only thing I didn’t see coming; the ending also took me by surprise.

AH: Yes. You think you’re guiding your children on the right path, and it’s the path that leads them to disaster, and you just never know. If you turn right, you have one life; if you turn left, you have another life. And you just don’t know which is the better turn to take. Looking back, I was kind of surprised by the sadness of these stories. Well, what do they say—you either write about joy or sorrow. There’s a lot of loss: this woman, this mother, who is a grandmother in the next story, she really knows how to love someone, and that’s not so easy in this world. There’s a sense that loss can happen to anyone, that no one is really protected, that this is what it means to be human, and this is just what it is.

CT: I think one of the things that struck me about this story is that it’s so understated. The tragedy is very matter-of-fact, the way it’s delivered—I mean, you could almost miss it. It makes the sorrow feel bigger.

AH: I have to say I really like that as a reader. I think that’s why I’m such a huge fan of Elizabeth Strout, because her stories are always a surprise. They have this emotional twist that’s so understated. You don’t even know you’re going to be walloped with emotion until you are.

••• Read Alice Hoffman’s “All That I Am and Ever Will Be,” published in Harvard Review 31 •••

CT: The second story, “All That I Am and Ever Will Be,” is a story I used to teach, and I always thought it was funny. What’s the context for this one?

AH: Shelby’s a young woman who has a tragedy that derails her life. She’s in a terrible accident and she blames herself for everything. Shelby is, weirdly enough, a voice that’s closest to my own voice, even though she’s much younger than I am. I love Shelby—in fact, I named my dog after her. She has a very complicated relationship with her parents and she has to go home due to a family crisis; it’s really about a kind of love between a mother and a daughter. But the story, which ended up as part of the novel Faithful (Simon & Schuster, 2016), is also about a person who starts to be able to feel again. I think that’s what I’m always writing about, people who can’t feel for whatever reason, who are traumatized in some way, and they have to relearn how to feel. A second chance, you know.

CT: One thing I really love about this story is the banter. I think the dialogue in this story is so funny and natural.

AH: It’s like ping, pong, boom, you know, between people who know each other really well, who have been saying these same things to each other for decades. I don’t necessarily always write that way, but I think it was right for this book. This is what these characters were like, and this is the way they talk to each other. So it’s got this feeling of banter that I don’t often have. It was fun to do.

CT: This story is quite different from the other two, partly because it’s set in the present. In the other two stories there’s more of a sense of panorama, of looking back. They’re more descriptive in in that scene-setting way—more landscape, more nature—but the strength of the characters is the same in all of them.

AH: Shelby reminds me of my original voice, you know, the closest-to-my-heart, who-I-am voice, and how I started out. But that’s why I’ve written so many books, because I don’t want to write the same thing over and over. I think I probably used to plot a lot less than I do now. I used to just let the characters walk in the door, and they just did whatever they did, and then in my revisions I would fix it up. Now I tend to have things plotted out before I start.

CT: Does it make it easier to write once you know what’s going to happen?

AH: No, I think it’s easier to let the characters just evolve the way they’re going to and then fix it later. But it may also be because I was a screenwriter for twenty-five years, and so I got into certain habits of plotting things out and having a big board and Post-It notes. I started to think in a different way, which in some ways was helpful. A lot of people who are writing a book, especially for the first time, get stuck wondering what the book is about. I find that myself. I’m like, What is this? What is this about? I always feel like there’s an outside story and there’s an inside story. The outside story you should know as a writer, but the inside story I think it’s better if you don’t know so you can discover it. An editor once said to me, Well, what is this about? And I was like, But that’s why I’m writing the book.

••• Read Alice Hoffman’s “The Year Without Summer,” published in Harvard Review 37 •••

CT: I recently pulled this issue off the shelf to show it to one of our interns and came across this story. It struck me because I had just been reading about the 1815 explosion of Mount Tambora, which I don’t think I even knew about when I first published “The Year Without Summer.” So, tell me, how did you happen to write this one?

AH: I was just kind of dipping around in history and I found out that there was a big year without a summer in New England. So then I looked it up, and there was this volcanic blast that was a hundred times as large as that of Mount St. Helens and it sent so much stuff into the atmosphere that it affected everything across the world.

CT: There was a killing frost in New England that summer and a big blizzard, which you write about in the story. This one is also a story about loss—about a family who loses a child. But it’s also a story about escape.

AH: And about falling in love.

CT: And it’s also got a kind of sneaky ending. You’re reading along, and you feel the time passing, and you gradually become aware—the way you would if you were looking for someone lost at sea, or in a snowstorm—that the person can’t have survived because too much time has elapsed. In the beginning you’re thinking (like the characters), They’re going to find her, she’s curled up in some place. And then too much time passes, and it gets dark and night comes, and the whole question of what you’re going to find isn’t the issue in the end. That’s not it; it becomes something else entirely.

AH: I don’t know If I knew that when I started writing this story. I assume that I did not. It was a story about this attempted rescue of a six-year-old who was missing in this snowstorm in the summer, and it turned out to be about something completely different.

CT: This one was also published in a collection of linked stories, The Red Garden (Crown, 2011). Is there more about these characters in the book?

AH: The little girl is a continuing character. She becomes a part of the town; she’s a ghost that people see at different times in their lives, and the townspeople put on a play every summer and the play is about an apparition. So she becomes a sort of a theme, a sort of legend in the town, whereas the other person who disappears on that night is never heard from again. I think that’s the two different ways that I view history. In one way, you take something that happens and completely reinvent it so that it becomes a legend that doesn’t even have that much to do with what really happened anymore. And the other way is like the woman who doesn’t get to tell her story. Ever.

CT: So there’s the narrative, which is always changing depending on the needs of the teller, or the absence, which is the missing information that you’ve got to invent or fill in.

AH: I realize that what I’m doing is trying to tell a story that certain women never got to tell. I’m trying to tell it for them, or my imagined version of what it could be. It’s not the truth, but I’m trying to get to some kind of emotional truth because they just never got to tell their stories. The book is about the history of this town, but it’s mostly about the history of what happened to women whom nobody really knows the truth about.

CT: So, what are you working on now?

AH: I’ve just finished a historical romance that’s really about falling in love with a book. That’s what happened to me, and I think that happens to a lot of readers and a lot of writers, and I think it especially happens at a certain time in your life, when you’re about twelve to fifteen, you know, that age where books affect you in such a deep way. I mean the books that I remember the most are the books that I read at that time of my life.

CT: What were they?

AH: Definitely Ray Bradbury. I’ve met so many people who think of themselves as Ray’s kids, because he’s a father figure to so many readers and writers. His books have these fantasy elements, but they’re so moral. They’re about worlds that are black and white in terms of morality; they give you a roadmap when you’re searching. When I was reading as a kid I think I was reading to find a more interesting world. I was reading to escape, and I was really aware of wanting to know what other lives were like. It seems to me when you read certain books you feel known. You have that feeling of not being alone because that writer knows how you feel—reading helps you understand what it means to be human.

Published on January 18, 2023