Wound from the Mouth of a Wound

by torrin a. greathouse

reviewed by rl goldberg

torrin a. greathouse’s collection Wound from the Mouth of a Wound leaks. Out December 2020 from Milkweed, Wound is to liquids what animals are to a bestiary. Something gushes from each page: water, blood, saliva, tears, rain, gin, lake water, alcohol, gasoline, sweat, open hydrants, bile, piss, buttermilk, come. In this mesmerizing compendium of liquids, greathouse considers surface tension and containment: that is, what weight liquids can bear, and what shape they take when enclosed. Through this poetics of liquidity, greathouse teases out what flows, and what is stoppered; what is fluid and what is not; what can pass through and be evacuated, and what can only sit like standing water, accumulating detritus, rot, parasites, mold. The liquids in greathouse’s poems are sometimes the oceanic feeling Freud theorized, and are sometimes a deep, cold pool in which to drown. The poems in this collection ask: What is made to sink? Who is able to float? To what conditions must we accede when we float? Is floating such an easy, desirable thing?

Flotation is a homeostasis to which many of greathouse’s poems aspire, but they rarely achieve it. Instead: mouths flooded with blood and knocked-out teeth; bodies drained and hollow, barren like salted fields; phantom rain; the rough draft of a coastline. Often Wound registers as biblical, the body overwhelmed not only by an Old Testament flood, but also by a stunted, punished generationality. The collection modulates between two fragmented visions of family: the speaker’s family as “the myth of an animal devouring / itself,” and the speaker’s own sense, as a trans woman, of frozen generation: “The pill that births / this body into woman; The pill that murders / the potential of a child; The body hollowed / to a broken vessel.” In “Metaphors for My Body on the Examination Table,” greathouse details how these two fragmentary visions are a distinction without a difference; they both end in the same story. Or, like an ouroboros, they don’t end at all, but gulp down the same spirals of violence:

The snake choking on its own body; The drowned man’s hand

-cuffs; The chrysalis strangling

the moth; The mother of ouroboros giving birth to herself

& herself & herself &; The lie of omission;

A fistful of seeds becoming teeth;

The grandchild never held; The first dead son

My mother does not bury.

What feels biblical about these poems is not just the snake, not just the first dead son unburied, not just lines like “herself / & herself & herself”—a selfsame litany of who begets whom. As in biblical narratives, too, metaphor is as operative for greathouse as materiality. The collection concludes with “Ars Poetica or Sonnet to be Written Across My Chest & Read in a Mirror, Beginning with a Line from Kimiko Hahn,” about which greathouse notes that the poem is “in opposition of Michael Ryan and all other poets, educators, critics and editors who believe that neither the form of a poem, nor the identities of its authors, are relevant to the reading of that work.” (The identities from which greathouse speaks: “cripple, trans, woman, still alive.”) While metaphor allows greathouse to plumb these identities, their materiality is also always softened by something fluid, unsolidified, overflowing:

When I began to transition

it wasn’t into a daughter, but

instead a flood. Wide-eyed breach.

Birth of memory. I took the pills

inside me & out spilled blue

nail polish, ropes of silver chain,

my mother’s curls, my father’s

gin-drowned face, sky blue baby

clothes soaked in lake water, fish

hooks, sapphire earrings, spent

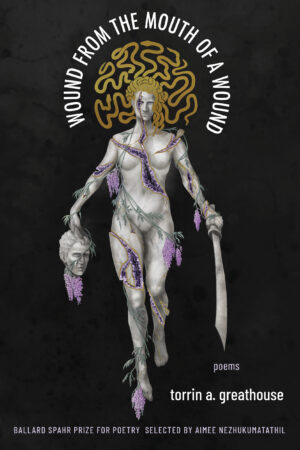

If the poems welcome biblical comparison, they also educe a commitment to form. The collection opens with a poem called “Medusa with the Head of Perseus”—a family mythology-as-ekphrasis, the image an occasion to consider transition in both mythic and formal terms. The physical shape of the poem—lines two-pronged and winding—evokes its subject: something split, decapitated, sliding; something to be cleaved, picked up, moved past, but never escaped.

My DNA, a two-tailed snake,

swallowing my father’s face.

I see Perseus’s head dangling

from Medusa’s hand & know

transition like this—to hold

a violent man’s face in your hands,

to set him & his blood aside.

There’s something of Ovid in these transformations; greathouse does not aestheticize violence and disability as aberrant, but attends to them and the way they make us. As the theorist Eli Clare might say, “marked bodies,” beautiful in their wounds and hurts. Is to be marked to be made into a metaphor? This question, too, floats in the collection’s subterranean lakes. But like Icarus in reverse, when the poems come too close to metaphor, greathouse pulls back from the seeping, the weeping, the still water; her poems combust. Icarus doesn’t fall into the water, but is dragged upward from it, higher, higher, his body lit up, catching fire. Or, as greathouse writes on metaphor’s surface tension:

Will not let this become another metaphor

for how my family taught me

my body as another name for pyre.

Published on January 25, 2021