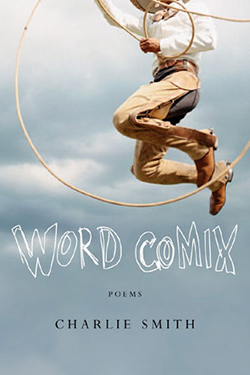

Word Comix

by Charlie Smith

reviewed by Shrode Hargis

There’s an intense loneliness that pervades much of Charlie Smith’s new collection of poetry. This isn’t new territory for Smith. Whether considering a former heroin addiction or a former lover, his poems usually zero in on men attempting to cope with life’s inevitable nosedives. In Word Comix we also find characters waiting, often searching for the next love or frenzy: “On my walks I hope to meet someone interesting, / someone I have been headed toward all my life.” The dread of solitude looms large, and the past sullies the future. In the wonderful poem “Clean,” we are faced with someone “follow[ing] the hog trail of longing,” metaphorically combing through desire’s trash heap:

It is here I find the endings that in their perfections of absolute loss

have become beginnings again, the bitten-off phrases and

inconspicuous wadding of spoiled opportunity about to start over.

Word Comix even features children “wandering the periphery, / looking for someone, you never know who.”

Some of these poems have the panicky quality of a midlife crisis, and the desire to be unlonely is compounded by the fact that Smith often uses humor to bank the projected possibilities. In “Like Odysseus, Like Achilles,” we encounter Homer “wondering / why at his age he’s still thinking of women” and then realizing “it’s not the girls, / it’s him, his craving, these broads, / he can’t shake the habit, the loneliness // and the harsh poetry of life are simply too much / w/out chicks in it”; in “Smarty Pants,” the speaker bemoans his jaundiced resentment for younger men who “live more fully / in the right now of dynamited redundancies and improvised / love affairs— // the little affairs I mean / in which some vagulous babe chucks a Chuck // under the balls / and goes whinnying into the night.” The result is a kind of gritty aggression that suggests at once repression and release.

Smith has a pastoralist’s eye and, as in his previous work, he brings this sensibility not just to rural settings but also to cityscapes. He has a knack for merging urbanites with what little nature persists around them. In a subway tunnel the wind from an arriving train “lifts a green, yellow and pale red maple leaf, / spins and tosses it onto a bench where a woman in / dark blue like an old-fashioned governess moves down a bit to give it room.” Another speaker, revisiting his ex’s former digs, remembers: “There’s a cypress on that block, two honey / locusts and an oak. I love those trees / like my own brothers.” Thankfully, Smith rarely over-sentimentalizes. In “Monadnock” a lone hiker makes his way up a semi-verdant, rocky outcropping, its

Scuff marks,

striations, frantically clawed areas, sulcations, ricochets

like tiny angels leapt up,…

…half-

healed wounds where forces violently made them stop.

Until:

the trees loosen their grip, give up,

and you climb among blueberries and mountain grasses,

turn, and look freely out as if you are not imprisoned.

But you are standing on a rock.

One could argue that the last line is implied by the previous, but the sentiment’s short, declarative nature effects a coarser, and thus a more true sense of closure. There’s no pathetic fallacy here, just “you” and the hard-hearted revelation of the world’s indifference, however beautiful that world may be.

Word Comix also showcases many of the gritty personae poems we’ve come to expect from Smith, talky sketches from men who’ve been left in the lurch by circumstance— “stranded down South America way, / drunk laid out / among Indian borrachos”—but still egg-headed enough to carry around works by Kafka and Henry Miller, or to invoke Desdemona and Shoney’s Big Boy in the same breath. I have often wondered how some of Smith’s poems would sound behind the chords of Steve Earle or the late Townes Van Zandt.

In one of the most direct and sustaining pieces in Word Comix, “The Greeks,” a man, sympathizing with his own “lack of advancement,” seems to talk inwardly rather than outwardly to the reader. The swagger that fills many of these poems is muted; the man’s posture, stooped. There is aggression here:

I remember waking up

after midnight thinking she’s such a Nazi about the damn covers.

Wanting out, going into the bathroom to argue with myself,

nearly stupefied with regret that I’d ever married her.

But there’s a refreshing transparency as well, so that the narrator’s thoughts and observations—a young woman in a coffee bar, a “bleating” homeless man, the fact that we’re all “a bunch of Greeks the gods have turned their faces from”—become less shaded by delivery and more moving. This brown study culminates in a striking metaphor of speculative emptiness:

Just now I’m thinking of old drunks, how their faces look doubled in size,

or the head shrunk, the skull back of the eyes,

brows tufty and separated by deep lines,

mouth slightly agape, lips slathered with a

purpose that’s nearly faded out, the space between them shadowy

as if they’ve taken a small bite out of the dark

and hold it in their mouths, waiting for a drink to wash it down.

Published on June 20, 2013