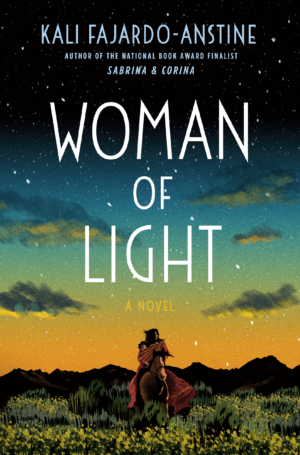

Woman of Light

by Kali Fajardo-Anstine

reviewed by Caroline Tew

There is perhaps nothing more popular in literature right now than a multigenerational saga. I’ll admit, anything with those buzzwords will catch my attention. So Kali Fajardo-Anstine’s Woman of Light, a follow-up to her debut short-story collection Sabrina and Corina, seemed a surefire hit. A Western set in early-twentieth-century Denver, the book boasts a tea-leaf reader with mystical abilities who must “save her family stories from disappearing into oblivion.” Unfortunately, too much page time was spent on the least interesting generation and their simple story, despite occasional lines of beautiful prose.

The book follows Luz, a tea-leaf reader who is suddenly responsible for helping her aunt make rent when her brother is run out of town. She gets a job and finds herself in a love triangle between a musician and her older boss. Throughout the novel there are brief chapters detailing the life of Luz’s grandmother as a Mexican gunslinger who accidentally shot her first husband when she was attacked by the dancing bear. She then opens a new theater with Luz’s grandfather in the Lost Territory, indigenous land that is slowly being infiltrated by prospectors. But the chapters recounting the story of Luz’s grandparents are few and far between, and initially it’s unclear how these characters are related to Luz. Not only did I finish the novel wishing for more of the ancestors’ past, but it also took me far too long to understand how these chapters were connected to the story.

Although Woman of Light illuminates the terrible treatment of indigenous peoples and Mexicans in the early-twentieth-century American West, the discussion of these issues is often uncomfortably juxtaposed with an unconvincing romance. A prime example is when Luz and David, her boss, are trapped in the office during a violent KKK riot. Under the table, the two begin fooling around, and Luz “had never experienced such a heavy want.” It is only when she realizes “if she let him, David would take her virginity right there on his office floor, in the middle of a Klan march” that she decides to stop things. In the end, the book is really about who Luz will choose: Avel, a musician on the run from being deported to Mexico; David, her Greek boss who spends his evenings in fancy restaurants that may not serve customers with skin as dark as Luz’s; or herself.

Fajardo-Anstine has a knack for describing small, beautiful moments. As Luz looks at the river, she sees that “young people had unlaced their boots and removed their stockings, wading into the moon’s reflection.” Or, when Luz first joins David for dinner in one of his exclusive clubs, she looks at the rich white businessmen and thinks, “Though they shared the same city streets, [she] often felt she and her people were only choking on their leftover air.”

Amid a plot that had so much potential, there were small nuggets of beautiful prose. Unfortunately, there was too much focus on Luz’s relationship status and not enough on her grandparents’ harrowing journey to create a life away from their homeland.

Published on September 20, 2022