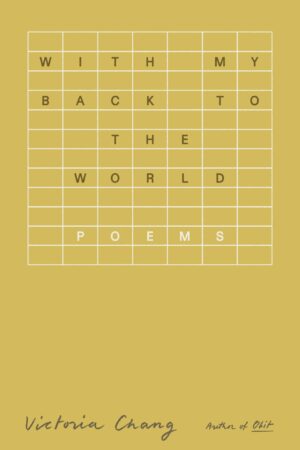

With My Back to the World

by Victoria Chang

reviewed by Emily Pérez

An ekphrastic prompt sparked Victoria Chang’s latest collection, With My Back to the World. With prose poems shaped like canvases and several images of her own, Chang’s book immerses readers in a deep conversation with the artist Agnes Martin’s pencil drawings and paintings. Martin’s oeuvre—comprising grids and stripes in muted colors—speaks to order and contemplation. In Chang’s deft hands, however, Martin’s grids become platforms for openness and inquiry. With its philosophical tone and use of visual media, the collection feels most akin to Chang’s book of epistolary essays, Dear Memory. The book brims with questions and conjecture, and Chang invites readers to query depression, grief, and the purpose of art. There are no answers here, only an ongoing conversation.

In an interview, Chang remarked: “It’s funny, I didn’t really know how depressed I was until I started writing these poems.” The collection provides many reasons for depression—a wounded, dying father (“I / close my eye all day to see if I can / feel your dying”); violence against Asian women (“I counted 44 lines and while I counted, 44 Asian women were touched”); the struggles of a teen child (“What to do if my daughter cuts herself and her arms look like Agnes’s lines”)—yet the poems are more interested in depression’s effect than its beginnings. In “Happiness (from Innocent Love Series, 1999)” Chang writes:

Depression is experienced. It is the CEO of feeling. All other feelings are direct reports. My depression is IPOing next month. It hopes to raise $100 million so it can expand into my future.

With dark humor, Chang depicts depression’s enterprising nature, its ability to subsume all other emotions. Most other depictions show depression as ongoing, existential: “Depression is a group of parallel lines that want to touch, but never can. Or maybe it is a group of parallel lines that only other people hope will touch.” The image conjures flatness that spills into the musings of the rest of the poem: “Maybe the earth is empty and the sky is full. Maybe life is only a holding room before death.” Beneath the speculations lie deeper concerns: is meaning here or elsewhere? must we navigate in isolation, never touching?

The emotional center of the book is “Today,” a twenty-page chronicle of Chang’s father’s decline and death. Sections appear like short entries under a month of dates. Chang blends the mundane and the surreal: “Jan.24.2022 / The funeral home calls and I open / your checkbook, a balance of mockingbirds.” The balance is illegible, “mocking,” a disconcerting landscape familiar to anyone who has managed the bureaucracy of a loved one’s death. Chang circles around the decision to withhold food and water, common in hospice care:

your arm grabs mine, as

if I am a messiah. But really

I withheld food and drink from you so that

your feet that loved to walk would never touch

the ground again.

The dynamic between parent and child is inverted—the child provides sustenance; the child is “messiah,” a god with the power to give or deny life. The image of the father’s feet never “touch[ing] / the ground again” can be read in multiple ways: he is deprived of what he loves, but he also becomes transcendent. The speaker struggles with power—is she merciful or cruel? A few left-hand pages depict a scroll of phone-sized screenshots of the poems. This gives the impression of pieces dashed off on a notes app, the harried process of the artist caretaker. Some screenshot versions are blacked out, giving extra weight to their corresponding text, as if we, the readers, have access to intimate, redacted moments.

Many of Chang’s visual pieces are erasures of poems—hatch marks and asemic writing obscuring the print. Because readers can see the words on the facing page, the orientation suggests we see meanings that might otherwise be masked. This dovetails with the book’s inquiry into the role of the artist. In “Fiesta, 1985,” Chang cites Martin: “Agnes said that painting is not about ideas or personal emotion, that the object is freedom.” She also quotes Mallarmé: “Paint not the thing, but the effect it produces.” In both cases, the artist must reach beyond the mundane to the universal feeling. Chang laments that the freedom of an idea disappears once it is fixed to a page. But perhaps more important than the freedom of the idea is the freedom of the artist to express an idea that can be received. In this collection, Chang creates the conditions for deep connection between readers and her work, for a sense of accompaniment on a path of inquiry. Perhaps freedom here is the freedom to intersect, to shed our isolation. In depicting “not the sky, [but] the beauty of the sky,” Chang reminds us of what we share and invites us into conversation.

Published on October 3, 2024