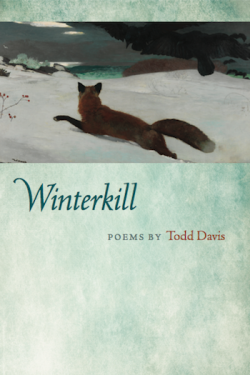

Winterkill

by Todd Davis

reviewed by Henry Hughes

“I believe, / despite my unbelief,” Todd Davis testifies in Winterkill’s opening “Homily”:

… Salvation is supposed to be sweet, like the sugar

of a wild grape, but where would we be without the fossil record to lead?

All of us are worth saving, despite the stink we’ve made since learning

to walk upright 400,000 years ago.

This collection’s negative capability of faith and doubt, spirituality and science, myth and natural history charges nearly every poem in both traditional and viscerally original ways. Davis tells us about Babylonian prophesies based on “the liver, / the seat of life and the dark river of blood / that might offer a message from God”; and then he remembers, “Every Thursday my parents fried liver / and onions” that “all tasted bitter.”

The poems, tied thoughtfully together in complementary pairs and threes, explore, among many forces, the power of animals in our lives and imaginations. Some claims strain our credulity: “Hearing crows talk, I’ve come to accept their intelligence rivals ours.” More often, however, the accounts—even in mystical narratives like “Crow’s Murder”—earn our attentions and sympathies.

… She knew

the boys who did this, sensed their hidden sorrow.[ … ]

The boys, who’d taken a stick to poke at her rigid corpse,

turned toward the tree where she perchedbut could not see her because she’d changed. The one

who’d fed her said he was sorry they’d done this.And the mean one hung his head and mumbled

that none of it meant shit.

Although the senseless destruction of nature is very different from conscientious harvest, every taking-of-a-life demands reflection and consideration. Davis, an angler, hunter, and professor of environmental studies, confronts an obvious and often unspoken fact of the human condition: our need to eat other living things. Citing lines from the early-twentieth-century Inuit medicine man Aua, “The greatest peril of life lies in the fact that human food consists entirely of souls,” he reminds us that plants are not excepted from this cycle.

Tonight at the supper table my mouth is filled

with meat, as I gnaw the bones of the deer

I watched eat pears from the neighbor’s tree.

Some of the fruit still bends the branches, planets

suspended in space: chartreuse skins

tendering a grainy flesh, slicked with the taste

of honey, and what I imagine is the soul’s

satisfying sweetness.

“How Animals Forgive Us” (quoted above), “Reading Entrails,” “Carnivore,” “Ode Scribbled on the Back of a Hunting Tag,” “Self Portrait with Fish and Water,” “Revelation,” and “Salvelinus fontinalis” are as revealing and engaging as the best fishing and hunting poems by Jim Harrison, John Engels, and Roseann Lloyd. If only Davis would ease up on the Latin titles, remembering that Thoreau ignored Alcott’s advice to call his book Sylvania.

Sporting over the hills and streams of south central Pennsylvania, Davis often finds, however, that aesthetics precede ethics. He holds and releases many brook trout, “the caudal fin / flays orange and ebony, a nimbus of flame / haloing the body.” And he refuses to hunt bear,

because when they rise up on hind legs

I see my dead father walking toward me,

and who wants to taste the meat that ushers in

such bitter dreams?

The poet’s father, a veterinarian and outdoorsman, haunts many pages of Winterkill. Like Sharon Olds writing of her ailing parent, Davis is unflinchingly candid and enduringly compassionate. In “Final Complaint,” he describes giving his father a home enema, “warm water mixed with salt in a red bucket, / as he’d taught me when I was thirteen at the animal clinic, the same / solution we used for dogs as sick as he was now … ” And in a touching farewell, “The Last Time My Mother Lay Down with My Father,” the poet asks, “How did he touch my mother’s body / once he knew he was dying?”

With her breast in hand

did he forgive with some semblance

of joy the final bit of fragrance

in the passing hour … ?

Finally, he tells us, that when his father died,

we helped her climb into bed next to him

where she lifted his hand to her chest

and closed her eyes.

In the book’s final poem, “Dreams of the Dead Father,” the speaker and his dad snowshoe into a winter grove, “where we find the melted beds / made by sleeping deer.” Like so much in this fine book, the empty impressions speak softly and clearly of what Wallace Stevens called the “nothing that is not there, and the nothing that is.” Winter’s absence and death remind us to feast on poems, remember, imagine, and survive into spring.

Published on June 5, 2017