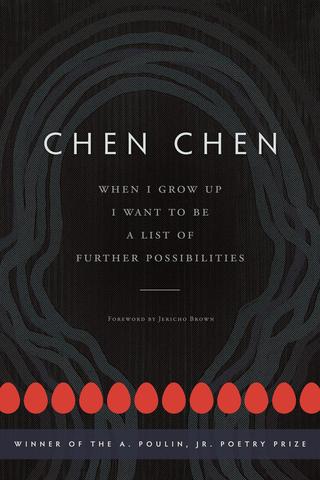

When I Grow Up I Want to Be a List of Further Possibilities

by Chen Chen

reviewed by Jeff Nguyen

What makes babies or manatees cute? Though small things come to mind first, cuteness describes an aesthetic encounter with anything that reads as helpless or vulnerable. To experience an object as cute, writes philosopher Sianne Ngai, is to respond to “an exaggerated difference in power” that arouses our impulse towards tenderness—but also violence. Yet if cuteness has the capacity to address such asymmetries, what role may it play in the struggle for respect?

The dreams and nightmares of the cute inspire the grief-laughter of Chen Chen’s When I Grow Up, I Want to Be a List of Further Possibilities. Winner of the 2016 Poulin Poetry Prize, this full-length debut bristles with bite-sized objects that bite back, as in the poem “In This Economy”:

… Often I am a countercultural pistachio

on a casual Friday. In one pocket, ChapStick. In the other, racist comments

from people who claim to be postracial. Or kind.

Groovy and absurd differentials of scale and agency intensify a “weakness for … miniature objects.” Tunefully tentative, his lines develop their personality from the freakishly (and syllabically) fragile image, anti-climactic enjambments, and the kind of off-beat humor befitting the literate immigrant. ChapStick, not Chopstick. He folds others’ hatred to the size of a pocket square, relieves the barb through his witty lip.

Since emigrating from China at the age of three, Chen has braved both the Texan wilderness and the New England winters as an unabashed queer and Asian American. When strangers, God, family, and friends diminish the speaker, Chen’s goal remains “to trick adults / into knowing they have / hearts.” His appeals to those above draw from the playbook of the hysteria patient (“I tried to confuse God by saying I am / a made-up dinosaur”), the songbook for indestructible toys, and the online guidebook to weaker creatures, as when—between wisecracks in “To the Guanacos at the Syracuse Zoo”—he apologizes for mistaking the llama-like “guanacos” for “guaca-moles” on a “little slice of Syracuse hill”:

… I mean of each of you sitting so still

with your legs tucked beneath your body,

& then your sleepy eyes. I mean,

the four of you were like a quartet of elderly

duchesses. (I’m sorry, later I looked you up

on the zoo website & found out you were all

males.)

Chen’s poems want to curl up beside you, before they lay it out for you. Still, he never abandons the comic’s aim of fits and giggles. The “little strangers” in one of his more experimental poems, “Please take your shoes off before entering do not disturb,” shows cuteness as an operation that makes language susceptible to deformation and transformation, turning high authority into the Swiss cheese of nonsense—or the gee whiz of bromance:

… report any suspicious

weathers Crouch to sniff out large unattended clouds If you

smell something say something say Nice socks nice boots

nice tomato soup & the clouds will vanish Do not say LeVar Burton

is my lover & Mr. Rogers my dearest friend quick LeVar Rogers

let us find what we need in this great country of burning

Warnings at home, school, church, and airport provide the raw materials of the poem (“report any suspicious activity,” for example). But the change in channel from national security to children’s television is delightfully impish. The fizzy spacing and enjambments dissipate the national hysteria and do-I-smell? doubt of the foreigner, even as they expose too the bitter truth behind the feel-good bromides of neighborliness or rainbow-high dreams that this “great country,” yearning with queer desire—or “burning” with racial hatred—has trouble living up to.

Comparisons to the O’Hara-Koch-Ginsberg camp are perhaps unavoidable. What distinguishes Chen’s feisty casual style is the way it unleashes the politics of the cute: “I don’t think I will ever stop trying to sneak / into casual conversation the word ‘ululation,’” he tells the pseudo-Buddhist preaching silence-is-golden to the classroom. His signature syntax is less Howl than Great Squall, squeaking with small talk, diminutives, jokes, queries, aphorisms, and inventories of the edible, from “fearless mango-tomato[s]” to the “inside bits / of our elbows … we’ve dubbed ‘bowpits.’”

Chen Chen commands the powers of the cute to address the kingdom of the crushed. His brittle and squishy lines appeal to our sense of touch, while making difficult affections, queerer strivings, and confrontations with power all the more palpable. This tart and startling debut leaves you awwing and awestruck.

Published on May 16, 2017