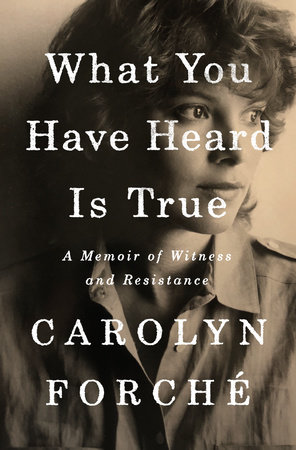

What You Have Heard Is True

by Carolyn Forché

reviewed by Carmen Bugan

Carolyn Forché’s memoir What You Have Heard Is True is the story of her coming to consciousness as a poet and as a human rights activist. This story begins in 1977, when Forché was twenty-seven and “too young to have thought very much about the whole of my life, its shape and purpose. The only consistencies were menial labor and poetry, and, more recently, translating and teaching.” She was already an accomplished poet (her first collection won the Yale Series of Younger Poets competition), but looking back, she sees that in her early work “there was no thread of purpose or commitment.”

Then a man from El Salvador called Leonel Gomez knocked at her door. In the back of his car were his two young daughters. Gomez’s name was vaguely familiar to Forché: a friend, the daughter of expatriated Central American poet Claribel Alegria, had mentioned him the previous summer during conversations about political unrest in El Salvador. Nothing had prepared her for what followed.

“Are you going to write poetry about yourself for the rest of your life?” Gomez challenged Forché, before inviting her to travel to his country with him and write about what she would see there. In the forty years since she accepted his invitation, she has become one of the most outspoken poets on human rights issues in Central America and beyond.

Gomez wanted Forché to join him in El Salvador because he believed a war was coming and that the United States had something to do with it. He never explained how he came to be at her door, but in their first conversation he spoke of his conviction that poetry could convey across borders the suffering of others and their hope for a better life. Forché was initially doubtful:

I don’t think you understand, Leonel [ … ] Do you know how poets are viewed here? We’re seen as bohemians, or romantics, or crazy. Among the poets I admire, there is one who waved good-bye before jumping from a bridge, another who put on a fur coat and gassed herself in the garage. Great American poets die broke in bad hotels. We have no credibility.

Gomez simply countered with, “Well, you’ll have to change that.” The war he predicted turned out to be extraordinarily bloody. Sparked by the inequality between the majority living in squalor and the wealthy elite that controlled the country, the civil conflict saw Marxist guerilla resistance groups fighting against the US-backed conservative government. The government death squads terrorized the country, and more than 70,000 people died, among them many women and children.

What You Have Heard Is True recounts the several visits Forché made to El Salvador between January 1978 and March 1980 and the extent to which those visits marked her. She credits her experiences in El Salvador with moving her writing from the realm of the personal into the realm of the political. In the introduction to her poetry anthology Against Forgetting, compiled many years after her return from El Salvador, she defines “poetry of witness” as “evidence of what occurred.” Such a poetry retains its interest in the workings of language even in the face of the brutality it presents. It also brings together the public and the private in an uneasy but necessary dialogue.

Gomez asked Forché “to learn what it is to be Salvadoran, to become that young woman over there who bore her first child at thirteen and who spends all of her days sorting tobacco leaves according to their size.” With him, she went to the houses of those engaging in resistance and of those who were unable to resist. She risked her life in order to meet a radio broadcaster who reported on the death squads; she also met poets who protested through their writing, a doctor working without proper medical equipment in an extremely remote area, and peasants sheltering guerillas. Living among communities where people’s spirits were crushed, she began to understand why the oppressed do not always fight back. After visiting a prison where people were kept in darkness, padlocked inside cages the size of washing machines with openings covered in chicken wire, Forché became sick, and Gomez said to her:

You’re exhausted, you’re shocked, you’re sick to your stomach, and you feel dirty. These things are what people feel everyday here—and you expect them to get themselves organized? You expect them to fight back? Could you fight back at this moment?

What You Have Heard Is True does not offer an analysis of the role of the United States in the country’s civil war. Instead, we get glimpses of American involvement: Monsignor Romero, the archbishop of El Salvador, appealing to the United States to stop funding the Salvadoran army; the American war photographer who would become Forché’s husband; the staff at the American embassy unwilling to leave the embassy compound. Forché presents truth as something personal and individual, verified by physical senses and therefore impossible to ignore. The smell of burning human flesh, the look of exhaustion and fear on people’s faces, the sound of gunfire in the walls of houses, the roughness of rugs used as mattresses: these truths cannot always be found in historical records, media narratives, or arguments about political partisanship.

In her collections Blue Hour, The Angel of History, and The Country Between Us, as well as in her teaching, Forché marries writing and activism. One school of thought holds that only victims of history should tell their story, and that the duty of the privileged is to empower those who have suffered to speak out. This memoir suggests that those who truly take the time to walk in the shoes of others will themselves be changed, and that when they speak out against suffering, they do so with authority. What You Have Heard Is True is a beautiful and important book of one poet’s awakening to the suffering of others and to the power of words.

Published on April 21, 2020