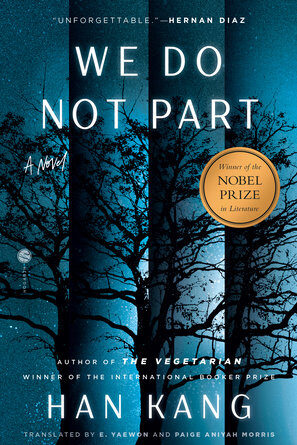

We Do No Part

by Han Kang, translated by e. yaewon and Paige Aniyah Morris

reviewed by Isabella Cho

Early in Han Kang’s novel We Do Not Part, Inseon, an estranged artist friend of the narrator, Kyungha, slices off two fingers in a carpentry accident. Inseon texts Kyungha with a request: to travel from Seoul to an ensconced village on Jeju Island where her pet bird remains, hungry and unattended.

Before fulfilling this request, Kyungha rushes to the hospital where Inseon is. She watches with awe and horror as a nurse administers a syringe every three minutes to Inseon’s bloody, newly reattached digits. It is a miraculous process, and an excruciating one. The pain is not a byproduct of Inseon’s re-fusing nerves; it is a necessary indication that healing is taking place. “I have to feel the pain,” Inseon explains to a mute Kyungha who observes, rapt, by her bedside. “Otherwise the nerves below the cut will die.”

Kang’s oeuvre is marked by an abiding interest in the body—specifically, the ways in which processes of survival transmute into acts of meaning. In Greek Lessons, for example, this process is speech; in The Vegetarian, consumption and starvation. These processes that Kang fixates on also possess a metafictional quality, offering resonances with the enterprise of writing itself.

In We Do Not Part, her first novel to be translated since being awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2024, Kang is absorbed by nerves. There’s strong evidence that Kyungha is autobiographically inspired. Kyungha begins having nightmares in 2012 as she commences research for a novel she publishes in 2014, about a massacre in a locale she refers to simply as “G—.” The same year, Kang published Human Acts, a novel about the Gwangju Uprising in which thousands were killed or wounded in a democratization uprising that was violently suppressed by the South Korean military. Through her research, Kyungha reawakens to a forgotten history—a kind of figurative re-fusing with a severed past parallel to the reconnection of Inseon’s dismembered fingers.

After such a protracted immersion in the violence and turmoil of a historical epoch, how does one recover their bearings in the present? This is the question that threads through the novel as Kyungha attempts to reacclimate to the rhythms of her quotidian life. Kang’s characteristic observational intensity—surgical in its precision, expansive in the atmospheric feeling it evokes—suffuses her novel with an air of disquiet. Vacillating between lucidity and fog, between the real and the chimeric, Kyungha muses, “Am I actually seeing this? Surely this must be part of my nightmare? And: How much can I trust my own senses?” As her confidence in her perception diminishes, she grows intensely aware of each fixture, each image, that she encounters: Everything vibrates with potential meaning. What was once inconsequential—or silent, or fungible—becomes vital with possibility, precisely because of its former dismissal.

That everything could be laden with meaning is not a cause, though, for celebration. Rather, it registers for Kyungha as a kind of sentence, the burden that comes with wading into history as a creative resource. In its emphasis on the potential presence of meaning in even the most banal encounters, Kang’s novel courts allegorical readings while refusing the faux neatness of a resolved or definitive interpretation. A prime example of this is Kyungha’s attachment to Inseon’s bird, Ama, whom she goes to after departing from her friend’s bedside in Seoul. The bird transmutes into a figurative portal for her other relationships—with Inseon, with the historical events that continue to haunt her—as though, by tending to the bird, she somehow might grow closer to mending her scars from other encounters. This inter-species bond, one that invites symbolism while never confirming it, situates Kang’s work in a broader tradition of contemporary fiction that plumbs the relation between artist-protagonist and pet. Sigrid Nunez’s The Friend and J. M. Coetzee’s Disgrace come to mind.

The distention of Kyungha’s reality into a wakeful dream is accentuated through scenes of snowfall. “Snow had an unreality to it,” Kyungha observes. “Was this because of its pace or its beauty?” Snowfall occurs during important moments: as Kyungha sits beside Inseon in the hospital, for instance, or as she makes the hazardous journey to the village for Inseon’s abandoned bird. Even the novel’s first sentence contains it: “A sparse snow was falling.” But snow is not just an aesthetic marker. It also portends Kyungha’s brushes with forces beyond her control—dreams, flashbacks, the strange and shifting intimacy of her relationship with Inseon—in which she finds it difficult to tell whether she is moving towards destruction or repair. Snow is so delicate that a single touch of the finger destroys it. When accumulated over time, however, it becomes capable of overcoming us. This oxymoronic quality echoes Kang’s treatment of history: muted, often imperceptible, secreting itself into the mores and idioms that organize her characters’ lives until, abruptly, it ruptures their habituated modes of seeing.

Kang’s novel accepts, and deftly fuses, the opportunity and the hazard within this ethereal force. Snow’s strange qualities mark Kang’s style itself, a prose of taut, luminous economy through which we experience the movements of a psyche that feels both achingly close and very far away.

Published on April 25, 2025