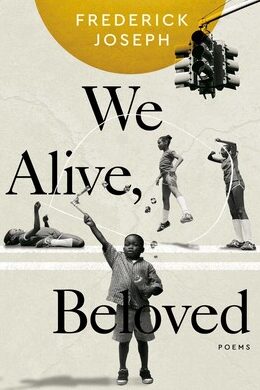

We Alive, Beloved: Poems

by Frederick Joseph

reviewed by Josh A. Brewer

Frederick Joseph’s first poetry collection, We Alive, Beloved: Poems, introduces a vital and resilient voice in American versification. We expect great things from an award-winning, New York Times-best-selling author as he turns from prose to poetry, and we are not disappointed. Joseph pens lyrical and critical poems in this volume; songs of himself, yes, but often poetry of a people—a collective—united and divided over race, gender, and love. We Alive, Beloved blends poetic and political manifesto with elegy, aubade, and serenade, and moves from critiques of white supremacy to encomia of Black art and joy.

In “I Don’t Read Reviews,” a poetic persona emails a myopic book reviewer and confronts him with the question, “Did you review my book, or did you review the scope of your own understanding?” This playful poem seems like an effective way to anticipate criticism while also claiming to ignore it. It challenges readers to accept poems for the songs they sing while critiquing the commonality of racial microaggressions in the literary world. Admirably then, and without spite, the book focuses on hope and community, not hate.

Joseph’s musicality allows for tenderness and critique. Throughout the collection, I noticed only one cliché: In the self-elegy-as-love-poem “In Another Life,” the last line is “Listen for the sound of my heart skipping a beat.” This is a mere quibble, though, because the loving poem that precedes that line is beautiful and compassionate (and directed to Joesph’s wife, Porsche Joseph). There are several allusions across the collection. As with the book’s title, which may allude to Nobel laureate Toni Morrison’s Beloved, “In Another Life” resonates with another Nobel laureate’s work: Derek Walcott’s Another Life. In another melioristic self-elegy, “On Days I Am Dying,” Joseph turns Frank Ocean song lyrics into his own stanzas of hope:

Artists can be a buoy,

tethered to tomorrow,

uncoiling the sorrow

knotted in the throat.

Any attentive reader of Joseph’s book will have a similar experience with the poet’s voice: “In a stranger’s lyrics, there are letters / addressed to me, postmarked from dawn.” The elegiac poems seem, naturally enough, to be addressed to the dead and dying, but they are also clearly directed to the “We” from the book’s title, those of us who remain alive and beloved.

In the final poem, “The Colors Worth Seeing,” we’re asked:

What could be more beautiful

Than a child in the bathroom’s half-light,

Eyes wide, confronting the mirror—

Pressing a kiss to that rainbow reflection?

This image brings us full circle to the art on the cover of the book: joyful Black children playing double Dutch jump rope and blowing bubbles—little delicate floating rainbows. The poem continues:

Their laughter rings louder than anger of parents

Who promised to love them

[ … ]

And later, when they lay on a bed of blossoms,

What relentless wonder might be born of these petals?

We find this delicacy in Joseph’s odes and elegies, like one of those floating bubbles blown by a child, but we also find an obduracy in poems dealing with social commentary—a balance of the airy and the solid.

Floating in that balance, we find the poem “Session III: To Eulogize a Man,” in which we’re asked “Shall we gather tonight, in the ghost light? / So you might help me write the eulogy / For the people I once was.” The ghost light reminds us of the darkest days of COVID-19, when theaters maintained the sacred tradition of leaving an unoccupied stage illuminated by a single bulb, sometimes called an equity light. That illumination in the face of death seems to be the perfect metaphor for Joseph’s entire book.

Published on January 6, 2025