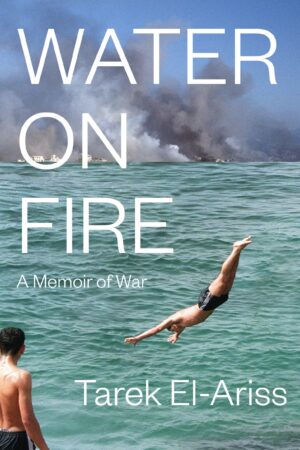

Water on Fire: A Memoir of War

by Tarek El-Ariss

reviewed by MK Harb

Born out of a love for the waters of the Mediterranean and the swimmers who dot its shore, Tarek El-Ariss’s memoir, Water on Fire: A Memoir of War, is a deep dive into civil-war Beirut and the stories of the families who chose to stay. As El-Ariss writes, to remain in a city torn apart is precarious:

We found a way to live around war, on its side, at its limits, in between bombs and abductions, fuel and power shortages. And we had the sea and the privileges of those Beirutis who could go to the beach every day, especially when work was slow and school was closed.

Living “around war” is a process of making many drastic adjustments. It is a mother resorting to homeopathy to create a system for organizing life amid chaos. It is wrestling militias out of the vacant homes of your neighbors. It is understanding the lifeline of water and creating makeshift systems to distribute it when times are severe.

In narrating these difficulties, El-Ariss questions his father’s decision to stay in Beirut. “Perhaps he was afraid to leave,” he says. When El-Ariss’s father returns from his medical studies in the US, he is one of just seven physicians practicing in Beirut, keeping his clinic open even during the toughest periods of infighting. Often, he reminds his family that they are the “courageous ones”: a mantra for moving forward.

El-Ariss goes to school at the Lycée Franco-Libanais, famous for its strict French laïcité in a country spilling over with sectarian tension. Despite the conflict, his family insists on living a vibrant life, often hosting house parties, attending musicals, and socializing in a way that might make the reader forget that this is all happening in a war-torn city. The Lebanese penchant for escapism is often critiqued as a denial of tragedy or normalization of it; El-Ariss complicates this narrative, seeing leisure as part of a larger and more cyclical relationship between pleasure and danger in Beirut.

As the war expands, destruction unmakes the streets of Beirut and military checkpoints turn into landmarks. Through this change, the sea remains one of the few bastions of familiarity, the beach offering a sort of theater, a place to be whoever you want to be outside of the prism of conflict. El-Ariss jokes that even during the most belligerent periods, people still found ways to tan and get the bronzed Lebanese look. However, this relationship with the sea is not just romantic or escapist:

Beirutis push the sea away like they push an overbearing mother. They claim their space and assert their independence by dumping garbage and pouring concrete. And the sea hits back by cradling foreign fleets that bring bombs and bondage.

In the chapter “The Boiling Cauldron,” El-Ariss expands on Beirut’s relationship to suffering by narrating the history of the near-extinct dessert mufattaka. Made of sticky turmeric rice, this communal dish requires a legion of cookers and an ungodly number of hours to prepare. For Beirutis, this process represents the patience of the prophet Job and, by extension, the patience required of them to endure in their city. When the muffataka is ready, families take it to the sea, eating and bathing—water summoned to heal and preserve.

After the official end of the war in 1990, Beirut reinvents its borders and removes the checkpoints demarcating East and West, making room for more invisible lines of violence. El-Ariss describes Beirut’s downtown, the city’s core that becomes the heart of carnage: “These dogs that inhabited the abandoned city center emerged like the rats in Camus’ Plague, spewing terror from the belly of the earth.”

The military is deployed again, but this time to exterminate rabid dogs and the ghosts of past terror. With the cleansing of the past comes the rebranding of Beirut as a city “with no victor and no victim,” a catchphrase that the government uses to establish neutrality with the signing of the Taif Agreement, bringing Beirut into the “post-war” era. During this period, El-Ariss enrolls at the American University of Beirut, and his city transforms into a cafe of bohemian intellectuals who read the Marquis de Sade and engage in the thrills of queer rebellion.

At some point, El-Ariss settles in the United States, first in Austin and then in New York, to begin the trials of academic life. But his past in Beirut often returns to him in the forms of bouts of anxiety, sudden skin rashes, and feelings of restlessness. This leads him to a psychoanalyst’s office, where El-Ariss examines his life through its painful ruptures. Yet, in confronting Beirut, he refuses to label his past experiences as traumatic—retaining the stubbornness and the bravery of those Beirutis who still went to the beach.

Published on November 7, 2024