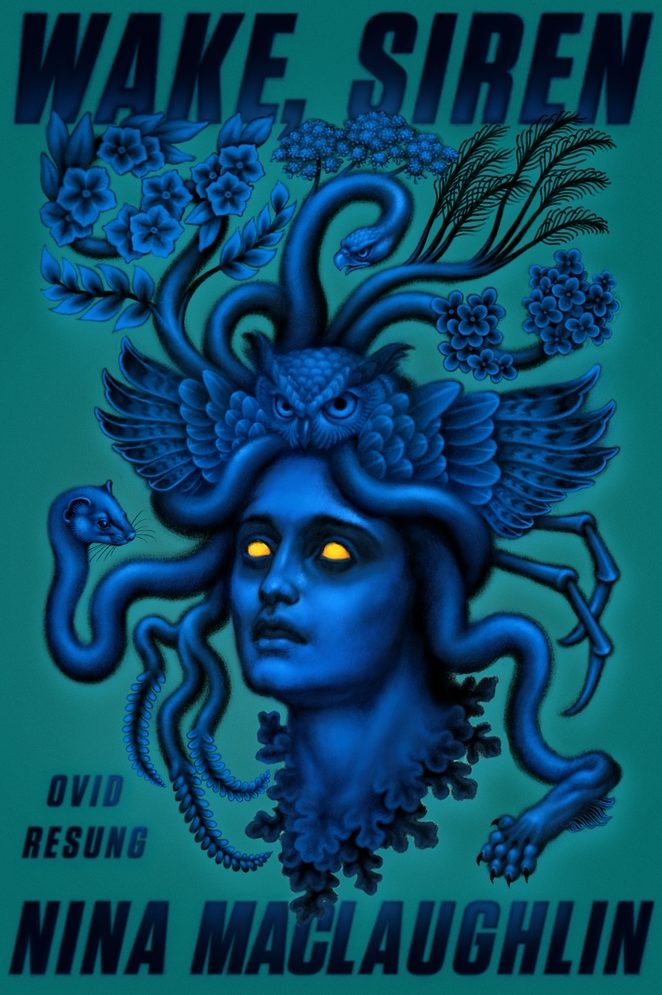

Wake, Siren

by Nina MacLaughlin

reviewed by Victoria Zhuang

Nina MacLaughlin’s short story collection Wake, Siren: Ovid Resung, like the recent Circe by Madeline Miller and The Silence of the Girls by Pat Barker, brings a strong #MeToo sensibility to bear on foundational tales of Western culture. All three of these works retell classical myths from the too often invisible perspectives of female characters, but where Miller and Barker each speak in the voice of a single woman, Wake, Siren offers a democratic chorus. Here Arethusa, Medusa, Callisto, Echo, and many others, taken together, embody a colorful sort of women’s march. “I can hear laughter in my mind,” one of them says. “All the women laughing. Just like the most righteous, untamed, victorious laughter.” While in places the writing of this collection could be tighter, students of classical mythology will smile at the bold, cathartic reconfigurations of moments from Ovid’s Metamorphoses.

The collection begins with Daphne, whose river god father turned her into a laurel tree when she begged him to save her from rape by Apollo. We discover that her spirit is still alive: she speaks in the imperative to her reader, from within a modern kitchen where she resides among the spices and herbs. “Open the cabinet. Move the cinnamon. Move the nutmeg,” she tells us. “There, the small jar with whole leaves the length of your pinky. Those are me, mine.” In traditional versions of her story, Daphne has to rely on a man for her strength: she obtains the freedom she seeks through the power of her father. In MacLaughlin’s retelling, by contrast, Daphne is the source of her own strength. She confidently declares who she is and what she owns: her body, all of it. Her declaration is like a quiet manifesto. She goes on to recount her escape from Apollo, setting the tone for a collection in which all the women are in some kind of revolt.

Wake, Siren uses the voices of these women to cast the many rapes and sexual assaults of classical mythology in a new and estranging light. Io, for example, tells of her abduction by Zeus and reframes her literal metamorphosis into a cow as figurative dehumanization:

My words had no power. I was speaking the language of animals. I could not make myself understood. I was no longer the full human self I knew myself to be, who is friends with Linda and Daniel and Quinn, who loved grapes as a kid and hated socks [ … ] All at once that went away and I was a body and an entrance and a means.

In the directness of her register—Io speaks not in some flowery classical way, but like a girl you might meet today—the brutality of the Western mythic past is excavated and its barbarisms shown to be ever with us. So MacLaughlin’s nymphs are everyday wives, tomboys, daughters, single mothers, and spinsters, as well as queens and monsters, and they metamorphose into women who swear, go to Pilates class, buy peanut butter, and don’t care what anyone else wants them to say or think. As one of them says: “People want to tell you what they know, like all of them have PhDs in being alive. One thing to know: no one knows shit.” And they transform: into water, into a bear or a lioness, into a different gender (in the case of Tiresias), or they take on a different gender role. These transformations celebrate women’s resilience and the fluidity of female identity.

Vivid as it is, the book sometimes feels overzealous and repetitive. Women in almost every tale are trying to avoid a very one-dimensional rapey man-god, who seems to be the same figure every time, albeit with a different physical form or name. There is the occasional variation, such as when a woman forces sex on the male Hermaphroditus—a story that sheds light on the oft-ignored plight of male sexual assault victims—but at some point the pursuits and idiotic cruelty of the male aggressors become dully indistinguishable. Perhaps that expresses the author’s view of rapists, but it could be made with greater concision. Elsewhere, some experimental portions fall flat. The Q & A with a therapist in “Myrrha” feels cheesy and cliché-ridden. And the rock club ballad in “Canens” falls heavily on the ear like an overearnest version of the hilarious drama of Pyramus and Thisbe from Shakespeare’s “A Midsummer Night’s Dream”:

A woman’s want is a dangerous thing

If you are to spurn.

Immortal hunger is bottomless

As my poor Picus did learn.

These qualms aside, Wake, Siren has enough verve, humor, and insight to be worth exploration. Among the book’s gems is “Baucis,” a radiant story of lasting love in an old couple who are granted their wish to cease breathing at the same time and be turned into intertwined linden and oak trees. “Procne and Philomela” brings the original story into a modern setting, truly capturing its horror, while the excellent “Euridyce” reimagines the tale of Orpheus and the tragic loss of his wife as one woman’s journey out of an abusive relationship. Here, Euridyce is a rising indie singer regretting her decision to marry the toxic self-absorbed rock star Orpheus. To escape from him, she chooses to descend into the Cobra Club, “where there was always room for one more. Even the sold-out shows. Everyone finds their way here eventually.” It’s a witty metaphor for Hell, death, and liberation from the control of another.

In a famous passage of Metamorphoses, Ovid wrote that all things in the human and natural world are destined to change: “For what was before is left behind; and what was not, comes to be.” MacLaughlin’s transformations of male-dominated narratives make Wake, Siren a timely and Maenadic successor to the subversive, genre-defying spirit of Ovid’s original.

Published on April 7, 2020