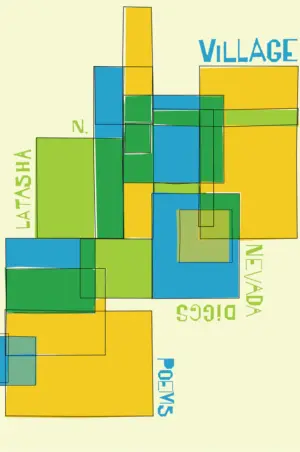

Village

by LaTasha N. Nevada Diggs

reviewed by Esther Kondo Heller

LaTasha N. Nevada Diggs’s second collection, Village, makes visible various “muted disasters”: the spatial erasure of Harlem, the loss of language, the death of her mother, familial estrangement, and historic silences. Out of this falling arrangement of piled disasters emerges a community of memory, images, and sounds, formed and composed by a poet of immense skill.

The collection is divided into five sections that include a “personal and artistic inventory” and a “kind of selective glossary.” The collection opens with “Performance”—an arrangement of logistical lists, requests, and wishes upon the speaker’s death:

- Speakers: i would like the following people

to speak: No one.

Just eat. Dance. Tell someone matter of fact/lywhat was really on my mind when they broke my heart. Or tried me.Offer a pinch of my ashes as mouthwash.

The official procedural language of these poems is unsettled by humor. Diggs addresses death with party plans, music requests, and food orders to remind us that we are all moving toward death, so we might as well make the necessary arrangements to have our lives remembered by those who survive us.

The poems in Village stun readers with several dwellings made of flesh and concrete. The apartment building and street are a “village”; Diggs introduces us to the units of the building and their inhabitants:

the Central American laborers return. today they demolish 4RW,

former home of Yvette, Brother, & their two kids.i offer orange juice & water to them as they are not as loud

as were Yvette’s fights w/ Brother

Elsewhere, in another poem in the sequence, Diggs writes:

Miss Daisy lived in 2FW . she distilled water by boiling it .

she sprinkled ammonia outside her door to ward off evil spirits .

my first period took place in her bathroom .

The building is a space where multiple attachments are revealed through memory and storytelling. These memories, punctuated by periods, trace the existence of the tenants and the building on the page. The periods in the collection, however, also take on other forms—they shorten, disrupt, and lengthen time, break linear speech, and allow for a stringing together of different voices, sounds and images. The period does not dictate a new beginning; instead, it makes possible an arrangement of recollected soundbites. For example, “mrs. goldstein” is written in lowercase:

war-veteran widow . repast undisclosed for the shared hagfish handler .

“later bitch” respects . no love lost .

Another punctuation mark that appears in the poem is the double colon. In some cases, it can be read as an analogy that establishes a relationship between two pairs of words. The usage of the double colon in “miss martha don’t remember mommy’s dead,” however, hints at a loss of memory. Here, the double colon becomes a symbol of erasure:

dream pictures :: dream a painting on cardboard :: dream

youth :: how the older ones don’t fade when lost for so long :: even

her disaster dreamt :: dream conversations w/artists :: dream of

In Village, Diggs wields sound, language, and imagery to arrange and compose a tragicomic poetic tour de force. She fills the page with an array of languages—Tsalagi, English, Portuguese, and German, to name a few—engaging in translation throughout. The collection holds its own liner notes. The final section, “personal and artistic inventory,” carries records of official documents such as Diggs’s and her mother’s identification card for food stamps, handwritten cursive notes to pick up liquor, and middle school exam papers. Village doesn’t merely contain the archive. It is the archive.

Published on November 9, 2023