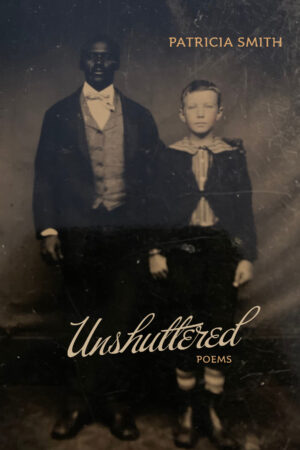

Unshuttered

by Patricia Smith

reviewed by Rhony Bhopla

Patricia Smith’s Unshuttered is an extraordinary work that elucidates Black consciousness in the form of dramatic monologue. The collection is a sequence of enumerated poems featured alongside found nineteenth-century photographs of African Americans. Reading Smith’s work, we are swept into a world of interiority, full of desire, love, joy, confusion, despair, anger, and resilience. In Unshuttered, a cacophony of voices responds to colonialist narratives about African Americans of the post-Emancipation period. Though we never truly get to know the people in the portraits, we meet them through the conjectural lens of the present.

In one photograph, a little boy with a benumbed expression looks into the distance; he appears to be alone in a clearing. On the facing page, “12” begins:

Daddy left me with one souvenir⏤a mutt,

a knotty mess of snaggled tooth and yap.

That dog just hated me. I’d sneak up near

his drooling trap

The quatrains of this poem describe the precarious life of the child. His anguish transforms with a shift in perspective; as he matures, he attempts to understand parental love. While the reader is enchanted by the lyricism of this poem, Smith describes a type of love born of something sinister:

I never knew

that kind of fright,and wondered what my daddy’s lesson was⏤

why he left me a dog that lived to sink

his fangs into my leg. Get used to him,

Pa said, I thinkhe must have meant to toughen me, to show

me just how crazy close I’d always be

to hate I couldn’t turn to love. The man

I am can seethe truth in that. But now I wonder if

I dreamed the mad dog real. He’s gone from sight.

He left the fear, nothing else. And was heblack

or white?

The disjunctive ending and artful pauses result in a suspenseful conclusion. Smith’s bold tone is familiar. Her previous collections, including Blood Dazzler and Incendiary Art, also contain voices of those who have been silenced in the face of violence. Similarly, the unmistakable intensity of her poems in Unshuttered heightens emotion. In “10,” a man in a tie states, “Step closer to me and see⏤I have not a thing to prove. I am a cultured man, and every curious eye that turns my way clings to privilege and chisel.” In a litany of directives, the speaker enacts the minimization of African racial identity. Smith’s depiction of this character’s contradictions, defensiveness, and even abhorrence serves as a critique of anti-Blackness.

Throughout the collection, Smith uses stichic and stanzaic forms, as well as traditional sonnets that leave the reader breathless in wonder. “11” is a stichic poem in the voice of a woman who is standing next to a seated man named Jim. She says he “works until / he weeps, claims to love / me more of his self / than he knew he owned.” Within this admission of delicate erotic pleasure is her tireless work:

I give him this square

body, nights of my voice

in his hair. I give growl

to a task. I slop the pigs,

pound nails flat, and live,

muscled and spent, next

to my man under a sun.

These poems demonstrate the startling power of a dramatic monologue. Unique to this collection is the graceful interplay between text and image, and the title Unshuttered dismantles the power of the photographer’s gaze. In “24,” the speaker directly addresses the photographer:

You’re driven by your thirsting for a pawn.

You covet me. And so I pose. You see

a jeweled mute, a prize accessory,

a sunrise you can latch onto your dawn.A word I held too close for you to hear

you never heard. And now, my sir, it’s late.

The gilded me behind your gilded gate

believes her skin. I warn you⏤don’t come near

The gaze is directed at the young woman, but she confronts it and warns the one who “gilded her.” Like many other poems in the collection, this poem encourages an understanding of unmistakable feminist power. The lesson of Unshuttered may be what Smith describes in the preface as the inspiration behind this multimedia collection⏤the moment when “the silence became a roar.”

Published on September 26, 2023