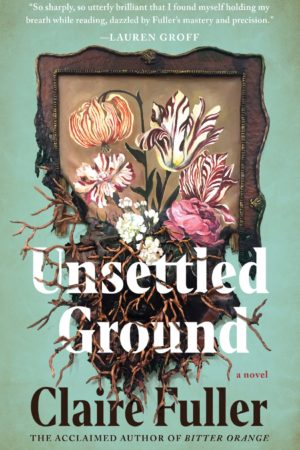

Unsettled Ground

by Claire Fuller

reviewed by Lily Rockefeller

In a secluded cottage in the Oxfordshire countryside, twins Jeanie and Julius wake up to find their only parent dead on the kitchen floor. If it’s possible for two fifty-one-year-olds to qualify as orphans, these twins—isolated, inhibited, distrustful of outsiders—are that.

Thus begins Unsettled Ground, award-winning author Claire Fuller’s latest novel, shortlisted for the UK’s 2021 Women’s Prize for Fiction. Shrewd, unsmiling, at times gripping, the novel is a midlife coming-of-age story for two adults once thrust into a grown-up world prematurely.

Fans of Tessa Hadley, another one of Britain’s bestselling contemporary novelists, will immediately think of her ruminative The Past, also centered on a fragmented family’s cottage in the English countryside. However, in contrast to Hadley’s lush English summer, Fuller’s England is damp and bleak. The cottage is mouse-infested and the meager family savings are kept in a kitchen crock, and yet in its fertile garden there’s enough bounty for Jeanie to feed herself and her brother for a week with no more than £3 worth of store-bought food.

Unlike the rotting fecundity of Daisy Johnson’s intensely metaphoric Oxford canals in Everything Under, in Unsettled Ground the question of money is always pressing, realistic, and stubbornly ugly. Jeanie and Julius barely have time to mourn their mother before their world falls apart more fully than they ever expected. Their wealthy landlord takes back the cottage, handing them an eviction notice with a strange allusion to their mother’s past. Jeanie discovers her mother was in debt, but the money that she borrowed is nowhere to be found. Searching for farm jobs to pay the rent, Julius is forced to relive the central trauma of his life—the day he witnessed his father’s death under tractor blades when he was twelve years old. Threatened with homelessness and hunger, burdened with heartache, the twins are forced on a journey, both inward and outward, that they never would have chosen to take.

The title of Fuller’s novel itself calls to mind the double-edged sword of rootedness. Even as Jeanie pulls up ruby-red radishes from the garden planted by her mother and Julius sings regional folk music passed down for generations, so too do they inherit a past whose devastating secrets run deep—and they find themselves rooted to the spot, with nowhere to run.

Fuller’s prose lies at the intersection of artlessness and artistry: unadorned but mature, avoiding the lyrical but, much like the graveness of the twins, full of its own dignity. While their isolated upbringing makes the twins hard to empathize with at first, I was impressed watching Jeanie’s evolution from reactive but timid shut-in to formidable and sensitive fighter. When Jeanie is forced to venture out into the nearest town to register her mother’s death, for example, Fuller nonchalantly captures their admirable self-reliance and their naiveté:

Tinny classical music is playing and on the wall there is a large painting of flowers in a vase—lily of the valley and roses—flowers that don’t bloom at the same time. She gives her name to the woman at the desk and sits in a chair. They are the same chairs in style and upholstery as the ones in the surgery waiting room. Perhaps waiting room chairs are the same across the country, across the world; perhaps one company has a corner on the sales of waiting room chairs.

Although I had figured out the central mystery of the novel just a quarter of the way through, far from being a letdown, its obviousness becomes a skillful indication of the twins’ stubborn refusal to face their mother’s secrets. And while its simplicity may suggest the story is more character-driven than plot-focused, the novel’s unpretentiousness makes it a page-turner and even a quasi-thriller—a rare feat for a literary novel. Literary but readable, reflecting the humble beauty of country life in every page, Unsettled Ground will appeal to a wide array of readers.

Published on July 2, 2021