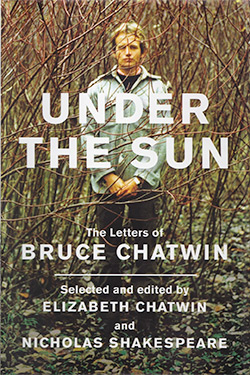

Under the Sun: The Letters of Bruce Chatwin

selected and edited by Elizabeth Chatwin and Nicholas Shakespeare

reviewed by Laura Albritton

When Bruce Chatwin died in 1989, at the age of forty-eight, he had already passed into legend. His mystique, his global nomadism, and most of all, his extraordinary books had won him an ardent following among readers around the world. In Patagonia, The Viceroy of Ouidah, The Songlines, and Utz were unlike anything else, imbued with shrewd English observation yet written in a loose-jointed, whittled-down style that seemed also American. Reading Chatwin you feel in the hands of a marvelous intellect, who read and digested history, literature, art, politics, archeology, and religion at a furious pace. He was the master of the ellipsis, but not a minimalist. His books seemed carved from a piece, rather than crafted from mundane language. After his death, his fans had two more gifts, What Am I Doing Here and Anatomy of Restlessness, both collections of his short pieces that now stand as classics.

Chatwin’s legend has also been kept alive by two biographies, Bruce Chatwin by Nicholas Shakespeare and With Chatwin by Susannah Clapp. Shakespeare’s book, at over 550 pages, is exhaustive; it uncovers many personal details that Chatwin carefully hid. It recalls sexual adventures, feuds, and illness with a graphic, unflinching persistence. The account of his decline from AIDS, his physical deterioration, and eventual dementia verges on the grotesque. With Chatwin by contrast is a book written by an editor who sees the imperfect man through the lens of his talent, and is more Chatwinesque in flavor. Which brings us to Under the Sun: The Letters of Bruce Chatwin, edited by his wife, Elizabeth Chatwin, and Nicholas Shakespeare.

The question one should ask about any writer’s letters is: Does exposing private documents, never intended for the general public, reveal something central about the writer’s process or the man himself? In other words, does the violation of privacy somehow become justified by the contribution such letters make to Literature? At the very least, does their publication help ensure his legacy? In the case of Under the Sun, the answer is not entirely clear.

We have letters and postcards to his parents, Charles and Margharita Chatwin. One from boarding school, dated February 1952, includes the information: “We had a jolly good film last night called ‘Riders of the Forest’ it was about a New Forest Pony.” A postcard from 1960 reads, “It rained today for the first time this summer. Spent weekend on island of Aegina where I met O Marlburian. Food very good. Xenias Melathon v. expensive and not as good as Tambi, at a third [of the] price. I had no cheque book so please will you pay for table-cloth and I’ll pay you back, B.” Another short note dated 1981 tells his parents that his novel is nearing completion, and “Spent a week repapering Homer End—which, I have to say, is extremely glamorous—if something of a threat to my writing.” At 560 pages Under the Sun includes many mundane passages that, while adding to the portrait of the man, are not exactly gripping.

One personal mystery about Bruce Chatwin that some readers might like to have illuminated concerns his relationship with his wife. Elizabeth Chandler came from a well-to-do American family; they met when he was the golden boy of Sotheby’s. There were people who were flabbergasted by their marriage because many assumed that Chatwin was gay. In fact, he was bisexual, but based on the evidence here it appears his true passions were male. The Chatwin who writes to his wife is the same man who appears in his biographies. He can be aggravatingly demanding in his requests: “1 pair of jeans please button-up 32 waist 34 leg,” “My canvas sided boots,” and “bring with you if you can some sensible but not sensational accounts of Peruvian Archaeology.” Many of the letters are concerned with their financial affairs: “If you are desperate for money, we will send some, but the question remains how much do you need and where do you want it.” The most interesting of these are those in which he confides to his wife about his ongoing struggle with a certain draft, or his passion for an objet d’art; we see how his seemingly effortless prose was of course not achieved without enormous effort. Also, we are given access to his curiosity for people and things that eventually he translated into literature.

Yet the mystery of their marriage remains. The letters reveal them to be partners, traveling companions, and best of friends but not lovers. (Which is not to say they were not.) What’s more, in the many, many footnotes included throughout the book, we are privy to minor marital disagreements. After one letter demanding a list of supplies, Elizabeth Chatwin notes: “I bought all this stuff and never used it because the camper was equipped.” About a letter to the filmmaker James Ivory, her footnote about her husband reads: “He was a wonderful guest, but a terrible host.” In another letter, Chatwin tells her he will find her in India, but she adds, in a footnote: “I went back to Bombay twice to meet Bruce because he said he was coming. I traipsed back, driving hundreds of miles, and he didn’t come, ever.” We are left with the impression of a wife wishing to have the last word; the comments would feel more natural in a memoir.

Another surprising aspect of Under the Sun involves the editors’ assumptions about their readers’ basic knowledge. Each reference to an artist, writer, politician, or thinker is diligently footnoted. Susan Sontag is described in a footnote as “American author and political activist (1933–2004).” Margaret Thatcher is footnoted as “British Prime Minister 1979–90.” The great Flannery O’Connor is reduced to “Catholic and reclusive short story writer (1925–64) from the American South who died of lupus.” These footnotes are hard to ignore and their effect is unintentionally comic, as if readers can’t be trusted to have heard of Borges, Mario Vargas Llosa, Karen Blixen, Pascal, Alain Robbe-Grillet, Josef Brodsky, and Margaret Mead.

There are, nevertheless, letters that will be a great pleasure for readers and admirers. The collection becomes engrossing when the letters closely follow Chatwin’s progress on his books. In 1985, he wrote to editor Tom Maschler as he was working on The Songlines: “Should we say it’s longer than anything I’ve attempted before. It is, I suppose, a novel: though of a very strange kind; but as I have the most unbelievable difficulty slotting all the bits in, I’d really rather not talk about it. One thing I’m sure of, is that it won’t be ready for publication this autumn. The fatal trap, I’ve discovered, is to think one is a ‘writer’ and to go in for all the paraphernalia that surrounds writerdom. So for what it’s worth, I’m keeping things a bit close to my chest.” The next year, while traveling in India, he wrote to his parents: “I have the most charming study to work in, and work I do. I have learned long ago not to make any prognostications about when this book will be finished. All I will say is that I’ve enlarged it considerably since I’ve been here. There’s a tricky passage to come, and after that . . . Well, who knows? But I’m afraid this gypsyish life cannot go on. I shall have, whether I like it or not, to get a proper bolt-hole to work in. Otherwise I find I can fritter away six months at a time without achieving anything, and that only makes me very bad-tempered.” One can’t help but wonder if this large collection, edited down to focus on “Chatwin on writing,” would not have been more compelling.

In his novel The City of Your Final Destination, Peter Cameron depicts a young biographer hustling to get authorization to write about a tortured, fictional author. The widow says, “If you write the book, I will seem a monster, and if you don’t write the book, I will seem a monster.” The biographies of Bruce Chatwin have already been written. In one of them Chatwin did at moments seem like a monster. In Under the Sun he speaks for himself. But not to us. The essential ingredient—of knowing Chatwin personally—that would give the letters that spark of life is absent. His letters were not performances for the public; all the footnotes cannot change this fact. He is, thankfully for his fans, fully human here. He is likeable, obsessive, intelligent, worried, and joyous, all of these things. Yet what was not revealed in the previous biographies is still in many ways obscured. For all the explication, we are no closer to his soul. And so we are left to return to In Patagonia and The Songlines. And surely that is for the best.

Published on March 18, 2013