Two Minds

by Callie Siskel

reviewed by Heather Treseler

Callie Siskel’s debut poetry collection, Two Minds, channels the haunting echo of private grief following the death of her father, Gene Siskel, when she was just thirteen. But as the title suggests, there is a second “mind” at work in this gripping account: a millennial woman’s critique of the inadequacy of family structures—and the trappings of class privilege—to salve a young person’s anguish. “Is death a sword that knights / the living?” she asks in “Mourner’s Logic,” interrogating the loss that sent her on a journey until she could return, as an adult, to examine her early history.

“No generation lives neatly inside another,” she observes with almost offhand profundity in one of the book’s opening poems, “Mise en Abyme,” a title that refers to an image within an image and, figuratively, to her own caesarean birth.

I was a lot to carry in summer.

High winds shook the round windows

for which the hospital is known.

It was a Saturday, midday; I was upside-down.

They cut her open to lift me out.

The swaddle and hat were too small,

so I was wrapped inside a towel.

The simple diction—“a lot to carry” and “upside-down”—suggests a story recounted to a child, curious about her beginnings. Yet the emphasis is not on the joy of the baby’s arrival but on the mother’s hardship and the infant’s unusually large size. From the outset, the narrator is made to feel she does not fit, such that she wonders, playing with her Matryoshka doll, “what it would be like / to live outside of one’s family.”

Solitude becomes her Freudian family romance as she realizes that the tragedy of her father’s early demise, “hiding … cancer,” is exacerbated by a self-absorbed and wounded mother who, in a subsequent poem, chides the daughter, “‘My pain is greater than your pain.’” The poet, noting “a jealous woman made me,” conducts her own excision in this book: extricating herself from her mother’s story and positing her own.

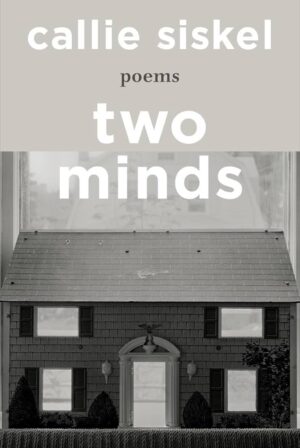

But how does one survive a “tongue that cut / … childhood in half?” A provisional answer resides in these poems’ truth-telling. The cover of Two Minds features a colonial house with opaque windows and a decorative bald eagle above the door. In carefully constructed poems, including “Marrying Houses,” Siskel riffs from Anne Sexton (as well as Sylvia Plath, Mona Van Duyn, and Louise Gluck) to deconstruct the American dollhouse with its narratives about girls’ and women’s lives, including the satisfactions of the mother-daughter dyad.

The poet considers what must escape such romanticized enclosures in order to live. In the squared-off quatrain that concludes “Marrying Houses,” she sums up her widowed mother’s macabre domesticity:

I think she wanted to show me houses

could be a husband, only more lasting.

Like a mortician, she made them

more beautiful than they were in life.

The mother’s obsessive creasing of pillows and polishing of brass creates an orderly world that resists the chaos of death. In the adjacent poem “The Cocktail Hour,” the mother’s new suitor arrives on the scene, and the poet recalls seeing his “Reeboks / straightened on the welcome mat”; comically, even the boyfriend is subject to tidying. Siskel’s sardonic tone is reminiscent of James Merrill, writing of his father in “The Broken Home” as a seventy-year-old “warming up for a green bride” with “several chilled wives / in sable orbit.”

Two Minds unfolds in five acts, akin to a Shakespearean tragedy, and symbolic parallels emerge. Unable to locate herself in domestic mirrors, the narrator seeks reflections of her experience in works of art. In the poem “Bird in Space,” she describes an art installation that features a bird “wingless, polished, unattended.” It is one of many artworks—from Titian’s Venus of Urbino and Modigliani’s Jeanne to Chagall’s Birthday and Friedrich’s Sea of Ice—in which she considers art’s contest with “the coffin of the frame” and how it enables us to consider “ourselves / in the ruins / of what we can’t traverse.”

Yet Siskel’s book provides us a kind of traversal. While many of her ekphrastic poems are about male artists’ perceptions of their female subjects, her poems resolutely frame her perceptions, tracing fissures in family life, an Ivy League education, and inheritances, personal and cultural. In one of the more moving poems about her father, a journalist who brought film criticism into American living rooms in his co-anchored TV show Siskel & Ebert, she tracks down the books of his mentor, the late John Hersey, in the library at Yale, imagining that her father read these same volumes as he honed the craft that enabled his future. In Two Minds, the reader is granted a share in that rich inheritance, the close reading of experience that allows for its transfiguration.

Published on April 18, 2024