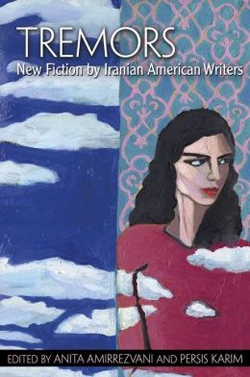

Tremors: New Fiction By Iranian American Writers

edited by Anita Amirrezvani and Persis Karim

reviewed by Elizabeth T. Gray Jr.

While we hear lots about Iran in the United States, it’s hard to hear Iranian voices. This anthology begins to correct that. Here are twenty-seven stories, written in English, by Iranian-Americans. Most are free-standing, some are excerpted from longer works. They are set in different places and contexts, told from different points of view, and reflect a range of styles—from graphic novel to lyric fragment to straightforward or surreal prose. What a trove.

The first group of stories, “American Homeland,” are set in the United States and explore the typical challenges and adjustments that beset eager immigrants and reluctant exiles arriving from anywhere: surprise, bafflement, loneliness, cultural misunderstandings, newfound freedoms and failures, external and internal discoveries and estrangements. In “In the House of Desire, Honey, Marble and Dreams,” the father in a family of recent immigrants is so undone by his wife’s new job and professional attire that he prevents her, and his children, from leaving the house for weeks. In “The Calling,” an Iranian woman living in America welcomes her sister from Iran, and becomes so homesick during the visit that she goes back. In the voices of these characters, Iran explains itself to America. As one woman explains the layered nuance of Persian politeness to an American friend, “Instead of ‘Shut up and let me talk for a change,’ a Persian speaker can say, ‘May I place a flower in between your words?’”

Iran is an ancient, sophisticated, and—to Americans—deeply foreign culture, one further distorted by the rhetoric of demonization that fills both countries’ media. What runs through these characters’ behaviors and perceptions, darkly, is Iran’s current traumatic history. In “Sabzeh,” we discover that the roots of an exiled mother’s focus on sabzeh, the special shoots of green wheat grown for the spring holiday of Nowruz, lie in the massacre of her husband and other Baha’is after the revolution. In “Family Trouble,” the narrator learns that her grandmother, whose ghost haunts the American apartment of her son and grandchildren, was killed by her brothers for wanting to be more Western in her ways. In “The Story of Mehri and the Old Women Who Once Were Young,” an elderly woman watches news coverage of the 2009 elections in Iran with her friends and is scorned because the sons who repudiated her are high-ranking officials responsible for the violence in Tehran.

The stories in the book’s second section, set in “Iran, Land of Resilience,” take us into the lives of characters who love, resist, and despair of their country. “The Ascension” is a tale in which childhood experience is inflected with superstition and magic. In “White Torture,” a woman in a prison cell thinks back on her life’s decisions as she awaits her certain punishment. Several stories detail the aspirations of young girls growing up in Iran, and the dangers incurred by those who dare express them. There is a section from the graphic novel Zahra’s Paradise and an excerpt from a fictionalized account of the life of Iran’s famous modern woman poet, Forough Farrokhzad.

The stories in the book’s final section, “Otherland,” are set elsewhere, and the characters are often not Iranian. In “The Wizard of Khao-I-Ding,” a Cambodian who fled Pol Pot acts as an interpreter to a team of Australians processing asylum applications at a refugee camp on the Thai border. In an excerpt from “Say I Am You,” an Iranian-American doctor barely escapes a suicide bombing in Kabul. In the American Southwest, a young woman gives a tour of a Native American pueblo community to a busload of tourists. While these stories seem cut from a different fabric than those in the first two sections, they are woven from the same threads: experiences of isolation, dislocation, and catastrophe; the meaning of family; and the long hand and aftermath of political violence.

This anthology gives us access to a world that has been largely invisible to Americans, but, more than that, it opens up to us an extraordinary range of voices and talents and makes it clear that as Iranian and American cultures come to terms with, and begin to understand, one another, an exciting high-quality literature is being born.

Published on October 13, 2014