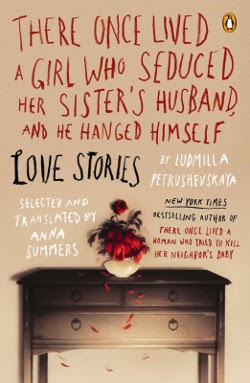

There Once Lived a Girl Who Seduced Her Sister’s Husband, and He Hanged Himself: Love Stories

by Ludmilla Petrushevskaya, translated by Anna Summers

reviewed by Jennifer Kurdyla

In the story that gives Ludmilla Petrushevskaya’s “love stories” its title, a man sneaks away from the beautiful yet troubled woman he impregnated in what he sees as an act of “temporary suicide . . . a thing that everyone desires at some point—to step out for a while, then come back to see what happened.” This startling interpretation of a common desire—to trade reality for fantasy—is pervasive in There Once Lived a Girl Who Seduced Her Sister’s Husband, and He Hanged Himself: Love Stories, a collection of seventeen tales of misdirected and desperate love.

For Petrushevskaya’s characters, reality in late- and post-Soviet Russia is about as base as it comes, and their fantasies are appropriately calibrated. Thus we get suicide—alongside child abandonment, domestic violence, and drug overdoses—instead of braid-scaling, dragon-slaying rescues of princesses in towers. But thanks to Petrushevskaya’s playfully macabre voice and brilliant narrative devices, these stories leave the reader with the same sense of victorious satisfaction for their heroines, even if happily ever after means a concrete room in which to build their meager nests.

Growing up in a broken home and then on the streets of Moscow, Petrushevskaya has been writing about the dire conditions of her homeland since the 1970s. Along the way she has received outstanding international acclaim for both her fiction and drama, including a Pushkin Prize in 2003. When her story collection There Once Lived a Woman who Tried to Kill Her Neighbor’s Baby was first translated into English and published by Penguin in the US in 2009, it hit the New York Times bestseller list, attracting attention for its sinister sensibility (the collection is subtitled “Scary Fairy Tales”) and garnering worthy comparisons to masters like Chekhov and Gogol.

In that same vein, There Once Lived a Girl has a claustrophobically domestic focus fitting to the stories’ settings: the communal spaces in which generations cohabit and the warped relations between relatives and lovers alike. Indeed, each story is just a few pages long—the longest is fifteen—but their concision emphasizes the intensity of expressions like “the smell of frugal poverty,” the “inhuman torture” of giving birth, and “pitying, tender love . . . as an etymologist might love a bug she’s discovered, even if it’s harmful.” These are the facts and also the fantasies for Petrushevskaya’s characters. What they long for is not a permanent escape but a salve to ease the sting of waking up each morning in threadbare hand-me-downs.

More often than not, it is women who inherit the crises, and maternity is a fraught topic. Petrushevskaya’s characters do everything they can to get away from their mothers—the past versions of themselves—but in so doing bring evermore future versions—their children—into the world with “heart-wrenching pity.” Husbands, too, are treated like children, nurtured in a way that renders sexual romance a means to the evolutionarily necessary end of love between parent and child.

This forced, almost resentful attitude toward love of all kinds is reflected in the stories’ narrative distance, which, for readers, turns out to be a blessing in disguise. Although Petrushevskaya first worked as a playwright, there is a curious lack here of direct speech. Instead, she translates hardship into her prose, giving a documentary feel to her otherwise wildly unbelievable sketches. This may also be why the first person only appears once, in the first story in the section titled “A Happy Ending.” There, we hear from Lena, who realizes that her “undying love . . . couldn’t coexist with the communal apartment . . . where my mother and I (officially homeless) were allowed to sleep.” So she settles for an “unhappy love,” and we almost wish that we did not have to hear this transparent desperation, to know that a fellow human could be satisfied with this as her ending—happy or not.

It is a testament to Petrushevskaya’s gift for compassion that she makes us love these people who find solace in the transitory spaces of train platforms and rented rooms and share in their happiness as much as their sorrow. She delivers the exact kind of escapism we look for in fiction. These are stories that remind us of what we are not, while preserving, with brutal and resonant clarity, the parts of ourselves we’ve stepped away from for a time.

Published on October 22, 2013