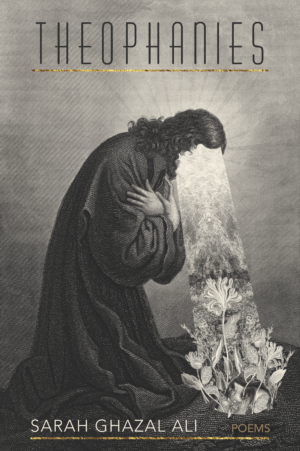

Theophanies

by Sarah Ghazal Ali

reviewed by Chloe Xiang

In Theophanies, Sarah Ghazal Ali boldly reckons with the patriarchal roots of Abrahamic religions. Turning to the Edenic figures of Eve in the Bible and Hawa in the Qur’an, Ali challenges the practice of a faith that interferes with the potentiality and power of womanhood. Hawa, who disobeys God’s rule and eats from a forbidden tree, anchors the origin of womanhood to impurity and vice. Ali reimagines this origin story by centering Hawa and removing Adam from the narrative. Describing the speaker of the poems as someone who bleeds, lusts, gives birth, and dreams of abortions, Ali wields visceral bodily descriptions and subversive transformations of religious narratives to assert that women and their wombs are the true bearers of humanity.

Throughout the collection, a strong first-person speaker critiques the reduction of women to their reproductive systems. In “Annunciation,” she recasts the moment when the archangel Gabriel tells Maryam that she will give birth to Jesus Christ. Ali subverts the traditional Quranic narrative and writes from the overlooked perspective of Sarai, Abraham’s wife, who remained childless till the age of ninety:

My pillaged body

is not as interesting

as my virginal sister’s,

I know. Your books

efface me, dismiss me

as naturally lacking.

Here, Ali rejects the idolization of immaculate conception while embracing the eponymous figure’s uncleanliness and infertility. By recasting the historical perspectives of biblical female figures, Ali’s poems come together to form a matrilineal line of spiritual history. Another prevalent motif in the collection is menstruation, and Theophanies challenges the taboo around this bodily function. In “Magdalene,” Ali highlights the messy, tangible, and painful reminder of the body’s readiness for a child, even when the person may not be:

We bleed as penance for the curious first. When we don’t,

…………we dread the burden borne by the immaculate second.

I submitted once, faithfully, and it was years

…………before I bloated with shame. He touched my hair with unsullied hands.

In “Magdalene,” Ali alludes to Hawa’s story and the consequences of her temptation that led women to shoulder the responsibility of fruit-bearing. The titular figure, Mary Magdalene, who is often culturally portrayed as a sex worker, becomes a reminder of how, after a sexual act, it is often the women who are deemed sinful. This point is accentuated by the male subject’s “unsullied hands” as he touches the speaker’s hair. Later in the poem, Ali writes:, “Doesn’t Islam mean submission? / … / I submitted faithfully to a man. What else?” She highlights the impossible expectation that women must bear children yet remain pure and abstinent.

Ali’s reimagining of worship forms an exploration of a contemporary and empowering version of faith. She imbues women with the vitality and autonomy that is often missing from religious texts. In “Self-Portrait as Mouthpiece of God,” she announces:

though I too was once congealed

blood, a mere clot,

and I too became

a clump of sinew, then grew

a body of man though I am

no man nor prophet

In these lines, Ali fluidly traces life through two generations—beginning with the speaker in the form of a blood clot and ending with its transformation into “a body of man” to symbolize the leading role of women in the creation of life. Ali ends the poem by correcting the title, writing, “not mouthpiece, but gaping / cervix … and still / a message worth hearing.” The surreal image of speaking through a cervix transforms the “good womb” into a meaningful platform; words projected through the cervix, as exhibited across the collection, are soaked in rebirth and independence.

In “Self-Portrait as Epiphany,” Ali conjures an image of parthenogenesis through a blood clot. She writes:

…………..Unashamed

I cramp. Between my legs

a clot. From a clot

…………..I’ll make men. Hollow

myself holy.

These lines encapsulate the thesis of her collection: the speaker is no longer embarrassed nor defined by her biological functions. Instead, she becomes the sole creator of men—the men who deem themselves deities and prescribe the rules imposed on her. Ali’s poems wield lyrical craft to extricate her faith from patriarchy’s contradictory and oppressive influence on religion and history. With Theophanies, Ali celebrates the mother line as something that rebels against the confinements of narrow belief systems and resists the inclination for women to be written out.

Published on June 2, 2024