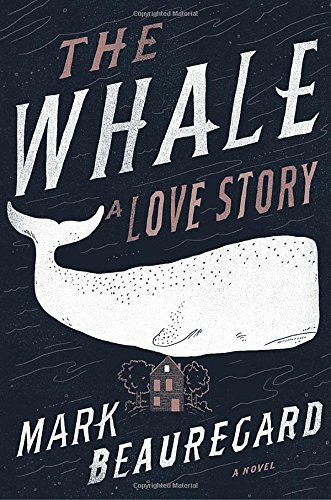

The Whale: A Love Story

by Mark Beauregard

reviewed by Erik Hage

Of all of the notable literary friendships, the bond between Herman Melville and Nathaniel Hawthorne seems among the most fascinating—largely because of Melville’s emotionally charged letters to the older writer, and also because the relationship became a crucible for the composition of Moby-Dick. In fact, Melville dedicated the 1851 novel to Hawthorne, in “admiration for his genius,” leaving no doubt about Hawthorne’s influence on the book’s eventual shape and scope. Many have also speculated that there was a romantic element to the relationship, and—speculation being the idiom of the historical novel—this is what propels Mark Beauregard’s The Whale: A Love Story.

Melville met Hawthorne in August 1850, a few months into the composition of the whale book. Hawthorne, having recently published The Scarlet Letter, had resettled his family in a small cottage in Lenox, Massachusetts. Melville soon relocated his own small family from New York City to a farmhouse dubbed “Arrowhead” in Pittsfield. With merely six miles between them, the 31-year-old Melville and the 46-year-old Hawthorne struck up a brief and intense friendship. Hawthorne’s letters to Melville have been lost, so we have only Melville’s missives: soaring prose performances full of adoration and lofty allusions.

Melville was at a febrile and expansive period in his development, having dashed out five books in the four years prior to starting Moby-Dick. An autodidact with very little schooling, he “swam through libraries and sailed through oceans,” soaking up sea experiences and books in equal measure. Hawthorne—both the man and his works—jolted something in Melville, who, right after the meeting, published a rapturous and suggestive essay, “Hawthorne and His Mosses,” about the older writer’s talent.

This is rich terrain for a novelist, and Beauregard has diligently steeped himself in source material. With scholarly precision, he assembles a world and constellation of characters out of painstaking and minute details. He even fills in blank space by rendering Hawthorne’s letters to Melville out of wholly imaginary cloth. Beauregard’s prose is at its steadiest when evoking the still and luminous flashes of Melville’s sequestered writing life. For example, the initial snowflakes from the season’s first storm outside his study evoke “the mystery of all life, in the transformations of water, the vast roaring swells of ocean … fluttering in crystalline loneliness.” Readers of Moby-Dick will recognize the adaptation of Ishmael’s meditation on water, in which he perceives “the image of the ungraspable phantom of life.”

Beauregard pieces together Melville’s inner life out of his writings, sometimes suggesting that his nonfiction praise of the older writer is redirected erotic energy. The fictionalized Melville pines for “the soft ravishments of [Hawthorne’s] beauty spun like a web of dreams,” whereas the “real” Melville, describing Hawthorne’s tales, wrote, “The soft ravishments of the man spun me round about in a web of dreams.” If the language is melodramatic, it is Melville’s own.

Assembling Melville’s personality out of the multifaceted, complex writings that he left behind is a Herculean task, and Beauregard is focusing, as his title indicates, on a love story. But this one-note Melville, the pining lover too distracted to work, is at times weighed down by purple tones and melodrama of Beauregard’s own making. While reading Hawthorne, for example, he “felt the man’s words bathing his soul.” At another moment, the “Sirens were singing celestial odes of Hawthorne in Herman’s ears, piercingly beautiful songs beckoning him to Lenox.” Our first glimpse of Hawthorne beholds “eyebrows that prettily framed his coffee brown eyes … sensuous red lips, the bottom lip a wide devouring flare; and waving chestnut hair that fell in ringlets behind his ears.” Elsewhere, a would-be seductress “grabbed two handfuls of Herman’s beard and pulled his lips to hers in a hard, dry kiss.” (Departing, she purrs, “Let me be your island girl in the Berkshires.”)

If these stagy flourishes occasionally weigh down and stiffen the novel, it remains bright in structure: the author shows a deft hand in unifying a compelling plot line with primary source material (Beauregard details his research in an epilogue). There is a great tradition of fictionalized literary biography, and though this work doesn’t hit the heights of, for example, Colm Tóibín’s adroit novel The Master (2004), which subtly yet evocatively rendered Henry James’s inner life as well as the emotional claustrophobia of his closeted sexuality, The Whale’s verisimilitude is admirable.

Published on September 13, 2016