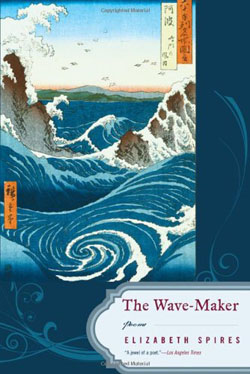

The Wave-Maker

by Elizabeth Spires

reviewed by Henry Hughes

Few poets would appreciate comparison to a snail, but Elizabeth Spires’ lens on artistic hubris and humility makes it quite possible. In “Snail,” the first of many garden-inspired pieces in her sixth collection, The Wave-Maker, she does the poet’s job of careful observation, wondering whether the creature is “like me perhaps” and asking the predictable “do you too feel terror?” All of this might make for a sluggish splay of backyard romanticism were it not for the honest conceit:

But we are different you are lowly & humble

you have grace & compression whereas I am awkward

& huge & not humble forgive me

Just as the humility-afflicted Anne Bradstreet composed superb verses apologizing for her awkwardness as a writer, Spires, a poet of impressive “grace & compression” asks forgiveness from a gastropod. One finds similar submissions to nature in the poetry of Elizabeth Bishop and Maxine Kumin, but Spires does it with less talk. Without dazzling language, it’s the glide-and-stop pacing and simple diction in “Snail” that calms us to believe that final obeisance: “I monster that I am bow down before you.”

Most art depends on some conceit, some pose toward how the world might be or feel at any given moment in the mind. We all know the disappointments of saccharine images and clichéd phrases, whereas the successful capture—however unrealistic—of an object, like a Hiroshige wave or a Tiffany lily, can crystallize and illuminate a new world. One feels this revelatory animation in Spires’ simplest poems, like “Brown Bird.”

You are brown, brown as a monk’s cowl,

brown as an old brown shoe,

brown as the earth the spade turns over.

Brown, not black, in winter’s patchy light.

As in children’s verse, the reiterations elicit playful meditations on the defining features of the object. Adult readers must be sympathetic to the conceit and, perhaps, adopt a Zen humility that accepts the innocence and simplicity of the language for the sake of higher truths.

Brown bird, your element is air,

but where are my wings? Where?

I am heavy today, heavy,

and have no tune or tone,

no light or life to share.

The charm of “Brown Bird,” with its Seussian rhymes and rhythms, and its simple pleas, reminds us that Spires is the author of several successful children’s books. And although The Wave-Maker includes poems that will delight young readers, adults may grow impatient with a five-page poem like “Essential Snail” that moves little beyond the cute and witty.

Do you want

to hear a beautiful word?Are you listening?

Are you really listening?Slime

Nevertheless, these elemental connections to a child’s way of knowing—particularly when they combine with East Asian minimalism and lyric folklore—are key to the success of the volume, which is on the whole balanced and mature. In “Badger Disguised as a Monk,” inspired by a Japanese netsuke, the enchanted creature tells us, “All motion is forward for a soul / with a pockmarked, bitten past. / But I will not look back!” The progression from enchantment to enlightenment also drives “To a Fog Spirit,” addressed to a twelve-year-old daughter on Halloween as she moves into those liminal shadows of selfhood: “Some mornings, impersonating one of us, / you wake, dress, eat, then vanish out the door, / the room suddenly too silent, the day clear as a bell.” The mother’s voice deepens into a mystical, haunting memory about pregnancy and childbirth.

And that night in January, after our long journey,

when we were almost there, and the bridge to the island

disappeared, and we pushed on anyway (did we have a choice?)

into the black foggy bottomless space and didn’t fall—

The nature of being is as mysterious and transient as a fog spirit, and years later the longing mother begs, “Rap hard! three times on the door, / and when it opens, as it will, / step through the portal and change, / change back into my daughter again.”

With a different approach to understanding the young imagination, Spires attempts a child’s take on “Sims: The Game.” Although virtual reality is well-exercised territory for fiction writers, few poets have taken seriously the presence and impact of computer games on the human imagination. Spires gives us a nice sample of the language a young gamer might use to describe this simulated world.

If you give them Free Will you don’t have to keep track of them

but it’s strange what they’ll do:

once a player fell asleep under the stairs standing up& sometimes they go into a bedroom that isn’t theirs

& sleep in the wrong bed then you have to tell them:

Wake up! That is not your bed!

The paradox of virtual and real in games has been self-consciously understood for a long time—this game called life—and we might expect more than a funny ramble, but it is fun to read “Sims: The Game” once and hear those qualified binaries we use to ambiguate what we trust as accurate or authentic. “In some ways it’s Life Real Life / in some ways Yes in some ways No.”

It would be hard to find a more banal truth about the games we play, the books we write and read. But perhaps that’s as close as we can get. Spires understands and is comfortable with human simplicity, both as an advanced philosophical discipline and as the absurd conceit of talking to a snail, or writing a poem.

Published on March 6, 2015