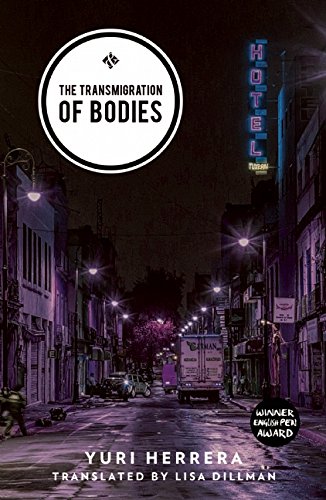

The Transmigration of Bodies

by Yuri Herrera, translated by Lisa Dillman

reviewed by Cecilia Weddell

A mysterious epidemic empties city streets and two warring families each hold in their possession a corpse belonging to the other. Despite the lingering contagion, a man named only as the Redeemer steps out of the safety of his home to orchestrate the swap of dead bodies, understand how these two lives came to be lost, and end a violent back-and-forth between the dueling families. Yuri Herrera’s The Transmigration of Bodies, translated from the original Spanish by Lisa Dillman, creates this high-stakes world infused with elements of myth and noir in just 101 pages, delivering a fast-paced and thrilling plot packed with wit, humor, and solemnity.

Herrera never names the city in which his protagonist works, refusing to locate the story’s dangers and cynicism geographically. The danger and corruption that the Redeemer faces can be easily connected to the novella’s nation of origin, Mexico, where institutional distrust is common, and especially so in the recent years of the ongoing war on drugs. But by giving his protagonist an indistinct urban space in which to maneuver, Herrera lets this story—and its lessons—belong to any place where fear and silence linger.

Eerie quiet is always in the background of the Redeemer’s adventure. From the start of the novella, “There was no one, nothing, not a single voice, not one sound on an avenue that by that time should have been rammed with cars,” and this silence persists throughout. The unnamed plague taking lives creates quiet in the city streets he drives between the homes of the wealthy Fonseca and Castro families. Little is known about the widespread disease driving people into fearful hiding, but a comically understated and contradictory statement from “the government” blames it on mosquitos—though, it adds, “just in case, you know, best to stay home and not kiss anybody or touch anybody and to cover your nose and your mouth and report any symptoms, but the main thing is Stay Calm.” Here Herrera criticizes a government that stokes fear as it feigns to handle the confusion and death on its streets, and also questions those who do not rail against their own enclosure and silencing. When front doors shut and stores close, the Redeemer is left unsettled: “He could sense the agitation from behind their closed doors but sensed no urgent need to get out. It was terrifying how readily everyone had accepted enclosure.”

With its hardened cast of characters and unforgiving setting, The Transmigration of Bodies sets the stage for a tenacious hero and delivers with the Redeemer, the sweet-talking professional middleman. His occupation is simply to prevent “it”—a word with many meanings, from angry ex-boyfriends to violent teenagers to the swapping of corpses—“from escalating to a major shitstorm.” He does so by approaching “the man who let himself be helped,” with the knowledge that “often, people were really just waiting for someone to talk them down, offer them a way out of the fight. That was why when he talked sweet he really worked his word. The word is ergonomic, he said. You just have to know how to shape it to each person.” Going in search of answers where things go dark, the Redeemer tries to fill the silences of these two unexplained deaths with truth. Along the way he interacts with a large, quasi-mythic cast of characters with names like Dolphin and The Unruly and Baby Girl, and discovers a long-hidden family secret.

Lisa Dillman’s translation expertly relays the urgency of the Redeemer’s story with lean, slangy dialogue and narration. She also manages to retain a link to its nation of origin, translating some Mexican idioms literally and adhering closer to grammatical norms of Spanish by leaving out quotation marks in the book’s dialogue. In her excellent rendering of this story, whose pages are packed with both affection and violence, we come to understand the Redeemer’s struggle with his work, and with the ethics of simply smoothing things over. When the dust settles between the Fonsecas and Castros, the hero reflects: “these days we walk past a body on the street, and we have to stop pretending we can’t see it.”

Published on March 21, 2017