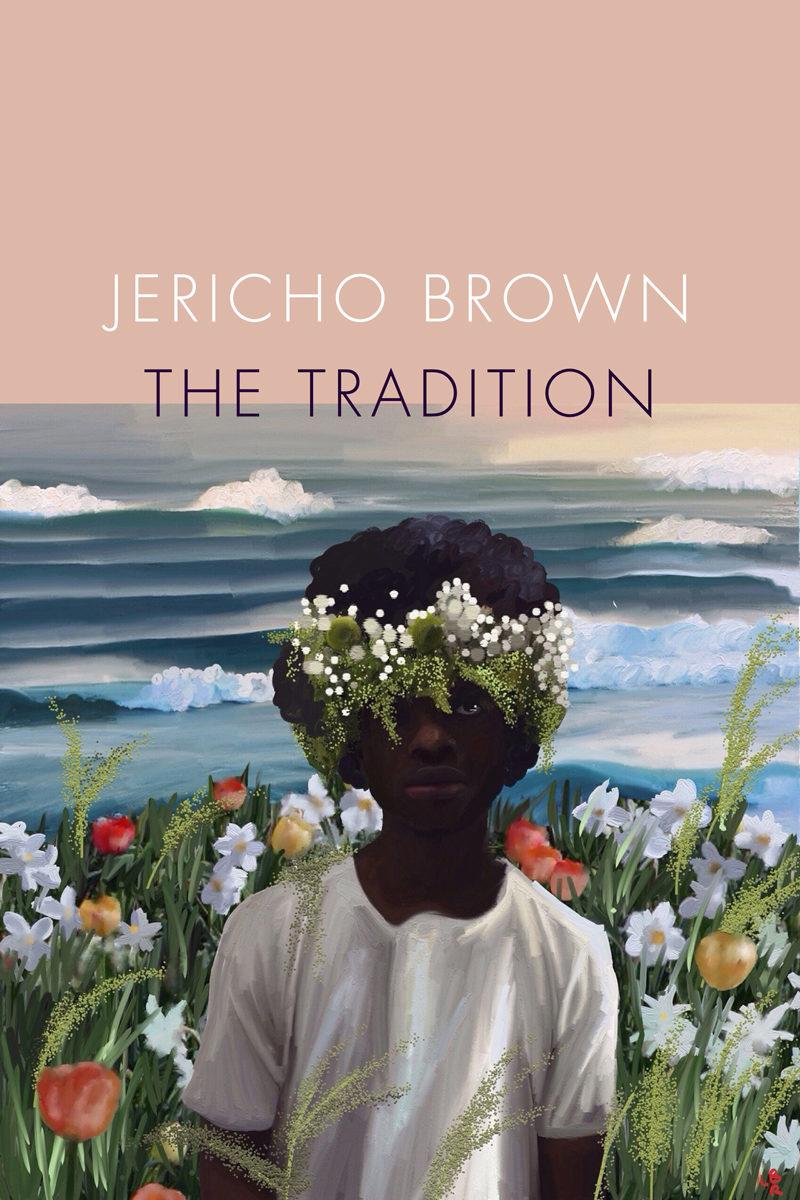

The Tradition

by Jericho Brown

reviewed by Leah Silvieus

Jericho Brown’s newest poetry collection, The Tradition, envisions the US social and political landscape as a pastoral. Brown’s pastoral, however, deals neither with the romance of the countryside, nor the sublimity of wilderness, but with the nature that we live among, cultivate, feed, and tend to in contemporary life: lawns, flower beds, the green spaces outside our windows. On one hand, that which grows in this country is beautiful, bountiful, joyful: the tenderness between lovers, or the speaker’s mother who “grew morning glories that spilled onto the walkway toward her porch / Because she was a woman with land who showed as much by giving it color” (“Foreday in the Morning”). At the same time, Brown’s pastoral reminds us that “All land owned is land once stolen” (“After Avery R. Young”), and that sometimes what we love is “green with deceit” (“I Know What I Love”), as the poems examine the other traditions that this country has nourished and sustained: racism, police brutality, mass shootings, sexual violence. These poems question what we grow, and why; what we bury, and where; and what stories and, sometimes, lies that the powerful tell in their attempts to absolve themselves of guilt.

Brown, adapting form and the pastoral mode in this collection, might be considered an inheritor of the traditions of other Black poets who reenvisioned received forms during the Harlem Renaissance and Black Arts movement, such as Claude McKay. As Sonya Posmentier explains in Cultivation and Catastrophe: The Lyric Ecology of Modern Black Literature, McKay’s adaptation of the sonnet envisioned the form as a sort of “provision ground,” a plot of land on the outskirts of plantations in Jamaica given to slaves to use for subsistence farming. In view of McKay’s sonnets as a “provision ground,” Posmentier suggests, his poems “Tropics” and “Subway Wind” can be seen both as products of his “cultivation as a British subject” and “his acculturation to and transformation of the form.” Brown’s invented form, the duplex, like McKay’s reenvisioned sonnet, also inhabits a liminal space with its intertwining of the sonnet, ghazal, and blues forms; as Candace Williams writes in The Rumpus, this form “holds tradition in its embrace while calling that embrace into question.” In “Pastoral and the Problem of Place in Claude McKay’s Harlem Shadows” in A Companion to the Harlem Renaissance, Jennifer Chang notes that McKay “found in pastoral an answer to the problem of placelessness: the poem could stand in for home.” Displacement also runs through The Tradition, but Brown’s speakers, rather than looking for belonging, use their displaced position to interrogate the implications of belongingness in the US today:

We do not know the history

Of this nation in ourselves. We

Do not know the history of our-

Selves on this planet because

We do not have to know what

We believe we own. We believe

We own your bodies but have no

Use for your tears. We destroy

The body that refuses use. We use

Maps we did not draw. We see

A sea so cross it. We see a moon

So land there. We love land so

Long as we can take it.

(“Riddle”)

The Tradition wrestles with the pastoral tradition down to meter and syllable, tracing back not only to the writers of the Harlem Renaissance but even back to Christopher Marlowe’s Elizabethan-era poem, “The Passionate Shepherd to His Love.” Examining Marlowe’s poem side by side with Brown’s “Dear Whiteness,” the similarities in diction are clear: from Marlowe’s “Come live with me and be my love, / And we will all the pleasures prove” follows Brown’s “Come, love, come lie down, love, with me / In this king-sized bed where we go numb [ … ] .” The echo reminds us that the nostalgia for imagined “purer, simpler” ways of life are not merely a contemporary American fantasy, but are deeply rooted in the English-language canon. Brown’s fraught, interruptive rhythm resists strict metrical cadence even as the poem seems, at times, lulled into a false ease. The opening couplets of both poems employ slant rhyme: Marlowe rhymes “love” with “pleasures prove” while Brown embeds his rhyme in an enjambment: “love” in the first line with “numb” in the second line. Down, even, to accent and syllable, Brown’s poems reveal how often pastoral fantasies belie threat:

[ … ] I am tired

Of claiming beauty where

There is only truth: the rabbits

Heard me coming and said

Danger [ … ]

(“The Rabbits”)

In the titular poem of the collection, also a sonnet, Brown draws a parallel between the three flower varieties with which he begins the poem—“Aster. Nasturtium. Delphinium.”—and the three names that appear at the end of the poem: “John Crawford. Eric Garner. Mike Brown.” Three flowers, three names, all in italics as if spoken. Nine syllables in each list. Brown explains on the Creative Nonfiction Podcast that he wrote these poems to be associative and to show the thinness of the boundaries between the poems (like the walls of a duplex house). “I’m thinking of these figures in a certain way and I’m trying to change our lens through which we see these murdered men, right? Then the title of the next poem is ‘Hero,’ because that’s the way I want to think of John Crawford, Eric Garner, and Mike Brown.” Asters, nasturtiums, and delphiniums are perennials—flowers that are often cut back in the winter months but grow to bloom again. Brown seems to suggest that despite the fact that this is apparently “Where the world ends, everything cut down,” this loss does not have to end the story. The Tradition is about the consequences of reaping what this country has sown, but it is also about that which grows in spite of, around, and beneath what our institutions have cultivated—that which survives despite the apocalypse.

One might consider The Tradition itself a continuation of Brown’s previous book, The New Testament, which concludes with a poem titled “Nativity” and the lines “Let that sting / Last and be transfigured.” As such, The Tradition might be considered a rewriting of Revelation, full of transfigurations, false prophets, disease, oppressive governments, the martyrdom of the innocent, the struggle between good and evil, and the prophecy of a second coming: “Black as a hero returning from war to a country that banked on his death” (“Hero”).

Published on July 16, 2019