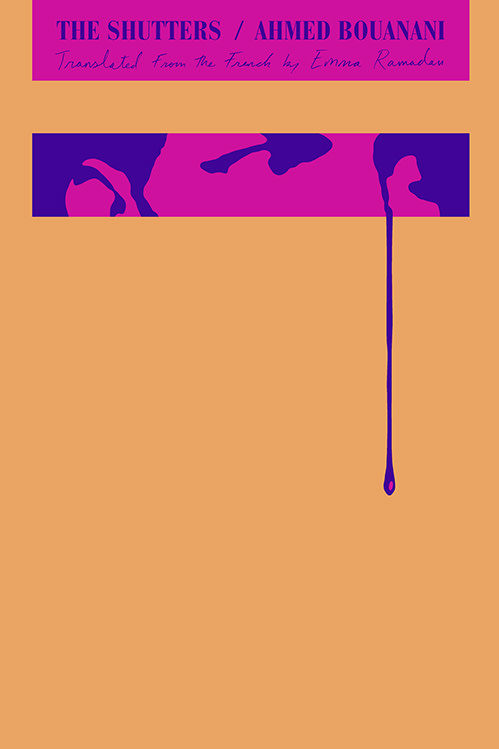

The Shutters

by Ahmed Bouanani, translated by Emma Ramadan

reviewed by Zack Anderson

“I lived in a house as big as a dream you don’t wake up from,” declares Moroccan poet Ahmed Bouanani at the beginning of the eponymous poem of The Shutters, newly translated from French by Emma Ramadan. Bound by a network of generations, houses, poets, myth, and the dead, The Shutters is both a vitriolic picture of the violence inflicted by colonial double-consciousness and a bitter indictment of post-independence policies that restricted cultural production in Morocco. Through the central metaphor of the house and a multiplicity of voices living and dead, Bouanani presents a haunted homeland, a domestic space that functions as both sanctuary and prison.

Employing both lineated verse and prose, The Shutters focuses primarily on the period of turmoil following Moroccan independence from France in 1956, when King Hassan II’s government violently repressed dissenters and artists during the “Years of Lead.” Accordingly, no specter haunts these poems more consistently than the dead poets, disappeared by the state, but still audible among the ubiquitous tombs: “In our country / out of Muslim charity / we dig them tombs, / and with their mouths filled / with dirt, our poets / keep on screaming.”

Throughout The Shutters, the tension between poetic tradition and the futurity promised by the avant-garde is made palpable through the figure of the dead poet. The strain is deeply felt in “Prophecies in Chalk,” the penultimate sequence in the collection: “They assassinate my words, they murder my past. / Must I, too, carry the shroud deemed sacred, / the fake cold shroud of your atrocious darkness, / and your kingdoms killed by the devoured verses?” As the sequence continues, the speaker begins to identify with the dead poets, and the pronoun shifts to a powerful, collective one:

Tombs await us, full of silence.

Even into death may our dreams journey,

perhaps they will moor in some haven,

a world where prisons are ancient ruins.

Hybrid hope of a languid poem,

deaf to the chants of a mythic generation

like a kite, straddling its history!

In “Prophecies in Chalk” and elsewhere in the book, Bouanani offers the liberating nature of dream as a counterweight to a tradition of myth that has become oppressive. In so doing, the author highlights the political thrust of surrealism as a means of imagining alternative futures. The “hybrid” poem is able to float above the clashing forces of tradition and colonial violence.

As a result of Bouanani’s ambivalent engagement with Arab myth, Scheherazade emerges as a pivotal figure in the collection. The famed storyteller from One Thousand and One Nights seems to represent simultaneously the degradation of Moroccan culture and the possibility of an imagined future. In the caustic “May Childhood And All Childhoods,” Scheherazade appears as a decrepit “old woman with no memory with no genitals, that old toothless / woman unable to blow out a candle.” Later in the collection, Scheherazade reappears at the center of the speaker’s utopian dream, repurposed through surrealist logic as a figurehead of the avant-garde:

Crouching memories! Let’s dream of the survival of Scheherazade-the-morning! Let’s dream of a Baghdad at the end of the street! Let’s prepare to suffer the death of our ancestors covered in Persian ornamentations who, in their silk shrouds, desperately attempt to erase every defeat for a slow eternity.

Bouanani tends to fixate on representations of women such as Scheherazade or “the horsewoman” al-Burāq to demonstrate the conflict between a lost cultural tradition and Hassan II’s repressive government. In fact, the women in The Shutters are nearly always either sexually objectified or portrayed as moribund and crone-like. This quality is consistent with the surrealist current Bouanani draws from, but may alienate contemporary readers. However, in “Five Memories Minus One,” the horsewoman becomes a poignant metaphor for the speaker’s liminal position, as well as for the experimental form of the book itself: “the theologians of the empire, sullen / that such an angel could exist in the world without them, // prepared to discover in their missals / that there’s a special corner of hell for hybrids.”

Thanks to Emma Ramadan’s masterful translation, The Shutters joins a growing canon of important literature from the Maghreb that has recently become available to Anglophone readers. The New Directions edition also includes Photograms, a more imagistic collection that extends the thematic preoccupations of The Shutters. However, the majority of Bouanani’s writing remains untranslated. This book serves as an excellent introduction to the Moroccan poet’s vatic tone, a voice that feels as urgent as ever:

From between our teeth come powerful legends

and strange poems from Isfahan!

From Isfahan or elsewhere… I imagine. The cities

melt onto our dreams to devour them.

Our prophecies,

we drew them in chalk…!

Published on April 11, 2019