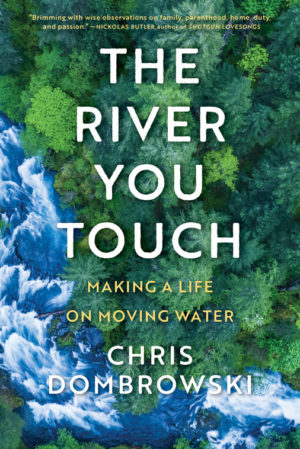

The River You Touch

by Chris Dombrowski

reviewed by Henry Hughes

Henry Thoreau wanted his nature-based Walden to be about everything, but he never had a wife and kids. Chris Dombrowski’s memoir about life in rural Montana—with all its hunting, fishing, foraging, philosophy, and home economics—is deepened by the presence of his wife, Mary, an elementary school teacher, and the children they share. “Raising three children,” writes Dombrowski, is “like fording a swift, waist-high stream whose stones are covered with moss; it’s possible, but move heron-slow, measure each step, or you’ll topple and end up who knows how far downstream.” Unlike most rod-and-gun sagas unsheathed from the sweaty leather of Wild West masculinity, Dombrowski writes with fresh sensitivity about his life with Mary, particularly about her pregnancies and act of giving birth: “I couldn’t begin to endure what she’s enduring; and for nine naive moons I failed to consider that my beloved would morph into my heroine.”

Tugging at this portrait of the artist as a married young man are worries over grocery money, mortgage payments, diapers, the environment, and his struggle to be a good world citizen. He worries whether he should be having children at all. This brooding may wear on some readers, and though the author’s heart is in the right place, he can be extreme in his personal consciousness-raising exercises: above his desk he posts the photo of a US-missile-struck Iraqi boy, Ali Ismail Abbas, a reminder to “repeat his name each day.” The child’s arms and legs are bandaged stumps and his entire family has been killed in the same attack. “This is the milieu, the maniacal moment, into which you’ve chosen to bring a life?” he asks himself. “How can you justify such a choice?”

Perhaps it’s easier to justify life choices if one writes beautifully about them. Rivers are Dombrowski’s poetic touchstone. As a naturalist and professional fishing guide, he boats, wades, and angles the magical moving waters around Missoula, Montana. In one luminous moment of connectivity, he brings a hooked trout to shore and sees “the fish as an elemental composite of its entire surround. Wildflowers dotting nearby hills had rebloomed in the red spots along its cheek;” its “fins mimicked the movements of a hovering kestrel’s wings; and the bluish white of its inner jaw reconstituted the hue of the first, barely noticeable star dawning in the east.”

This poetic prose is complemented by good storytelling, and Dombrowski has a gift for getting to know eccentric locals. Among these is Dixie, a master mushroom picker with a pet bobcat named Stevie. One spring morning the three of them climb into Dixie’s “jacked-up black F-150 with flames painted on the doors toward a fire-scalped ridgeline” in search of delicious morels. Though warned, Dombrowski can’t resist turning around and locking eyes with Stevie. What follows is “a moment of consideration wherein predator and prey gauge which is which, before the cat’s whiskered ears twitch and, in a mottled flash, her left paw swings up from the seat to belt me across the face.”

Dombrowski embodies a similar tamed wildness. He’s the informed parent-environmentalist who also hunts deer and pheasant, detailing the cleaning, butchering, and culinary preparations that help feed his family. One afternoon, a biologist friend brings him an elk’s heart that they slice and fry in olive oil and butter. It’s the heart of a cow elk that literally burst trying to defend her calf from a fatal wolf attack, and the men make a “feral toast to mothers and their calves.” The tribute feels authentic and “the meat is dense and leavening and tastes of timberline air just after rain.”

Engaging scenes also arise from Dombrowksi’s friendship with the late author, Jim Harrison, who died in 2016 and was forty years his senior. The young guide takes the wizened, chain-smoking, fly-fishing bard down a raging Rock Creek—“the boat felt shot from a sling”—and they later learn that a raft on the same stretch of river, that same day, had flipped and one person aboard it had drowned. They drink to calm their nerves, but Dombrowski is noticeably shaken. The next day Harrison prescribes a lavish lunch and “an ample midday pour.” Their talk ranges over many subjects, landing on the recurring issue of how one balances the long hours of writing, fishing, and hunting with family time. Harrison confesses that he tipped the scales toward the self, bluntly warning the young writer,“Don’t let your life become the sloppy leftovers of your work.”

Dombrowski can appreciate a venerable writer and personality like Harrison, but he’s equally awed when his three-year-old daughter, Molly Keats, asks: “If you were a bird and didn’t know what color your eyes were, what color would you want them to be?” The River You Touch chronicles the possibilities for an artistic, healthy, balanced, family-integrated existence where a rugged outdoorsman snuggles with his wife and children, recognizing that “there is nothing as wild and vital” as their company.

Published on November 15, 2022