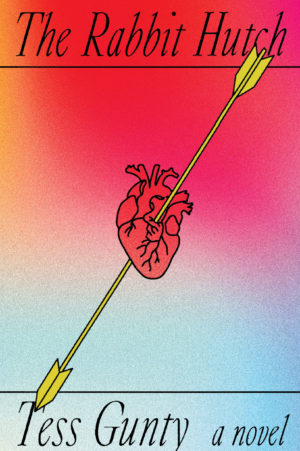

The Rabbit Hutch

by Tess Gunty

reviewed by Wayne Catan

Tess Gunty was raised in South Bend, Indiana, where she attended Catholic schools straight through college. In 2015, with a bachelor’s in English from Notre Dame under her belt, she moved to New York to study with Jonathan Safran Foer and Rick Moody at NYU. She brought with her a deep knowledge and love of the Rust Belt, which is apparent in her debut, The Rabbit Hutch. The novel is littered with Midwestern imagery: abandoned warehouses; jetsam from the once booming Zorn Automobile Company; a verdant valley; and a diner for townies, where the eighteen-year-old protagonist, Blandine Watkins, works.

Gunty wastes no time grabbing the reader’s attention with this opening sentence: “On a hot night in Apartment C4, Blandine Watkins exits her body.” The why and wherefore are the questions Gunty will answer over the course of a masterfully orchestrated multivocal performance. Our curiosity is piqued with each page we read, thanks to a variety of clever narrative techniques: obituary comments, epistles, and a chapter comprised solely of black-marker drawings.

Of all the places Gunty turns her attention to, however, it’s the titular Rabbit Hutch that is most suggestive. The Rabbit Hutch is an affordable housing complex in fictitious Vacca Vale, Indiana, where Blandine lives with three teenaged boys who, like Blandine, have just aged out of foster care: Todd, Malik, and Jack, who is “wound to the wrong moral time zone.” A spinster, Joan Kowalski, lives in C2; she works at Restinpeace.com scanning obituaries for insulting comments. A mom named Hope, who has “a phobia of her baby’s eyes,” lives with her family in C8. Reggie, a former engineer for Zorn, and his wife, Ida, are in C6; these two septuagenarians have downgraded to apartment living after losing their house. Gunty evokes the loneliness of apartment living in Vacca Vale:

The sensation that disturbs Blandine most profoundly as she walks across her small city is that of absence … Empty factories, empty neighborhoods, empty promises, empty faces. Contagious emptiness that infects every inhabitant. Vacca Vale, to Blandine, is a void, not a city.

In addition to unique characters, Gunty’s gift lies in capturing Vacca Vale’s character. The town exudes hopelessness—unemployment and crime are rampant, and it is ranked first on “Newsweek’s annual list of Top Ten Dying American Cities.” The city once “had a pulse you could feel in Chicago,” but that was when Zorn was booming. Yet Vacca Vale also has a certain cultural vibrancy: home to many who have never lived elsewhere, the city has developed its own patois.

So when a New York City developer and his team make plans to revitalize the city, Blandine is understandably not happy and coordinates a protest involving voodoo dolls, fake blood, and animal bones to put a stop to it. Through Blandine, Gunty’s message is clear: if you build in the Rust Belt, keep true to its roots and ensure affordable housing so residents are not displaced.

Much of The Rabbit Hutch focuses on Blandine’s loneliness and search for happiness as she drifts through her city, interacting with customers at the diner, her roommates, Joan in C2, and a music teacher. Although a high-school dropout, Blandine is an intellectual who reads Dante in her spare time and finds inspiration in the work of Christian mystic Hildegard von Bingen: “The earth which sustains humanity must not be injured. It must not be destroyed!” Blandine’s favorite place is one worthy of Bingen herself, the fittingly named Chastity Valley. It’s an orientation point, a place where Blandine can get her bearings:

[Blandine] can feel her whole body relax as she descends into greenery. Over a thousand maple trees live in the valley. Deciduous, the sugar maples are astonishing in the autumn, carpeting the woods in crimson, plum, and cadmium yellow.

As the rest of The Rabbit Hutch unfolds, the reader learns more about the music teacher, encounters several scenes of animal sacrifice, and witnesses the bizarre behavior of a former child actor’s son. But it is the activities of the four teenagers in apartment C4—especially one night after Blandine brings home an injured goat—that are at the heart of the book.

The Rabbit Hutch is deeply researched, and it is obvious that Gunty has a deep love for the Midwest. Still, the sections about Hope and her baby would work better as a stand-alone short story. Despite this shortcoming, Gunty’s colorful cast of characters and description of Vacca Vale capture life in a run-down postindustrial Midwestern city. In her portrayal of Blandine and her three roommates, Gunty lays bare the emotional trauma foster children experience, as well as their desperate need to transition to a normal adulthood—which might mean leaving the Rabbit Hutch for greener pastures.

Published on November 4, 2022